The massive call for racial equity, especially after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, spurred a rash of solidarity statements, hirings of chief equity officers, and efforts to launch external initiatives and programs to address racial inequities.1

We are certain some readers have heard or thought, “This is a fad; it too shall pass.” Partially this is due to the fact that many of these efforts focus on generating the external “proof” of racial equity. They tend to cherry-pick examples of new programs or initiatives without pausing to acknowledge that racially inequitable processes on the inside of our organizations lead to systemic outcomes that have historically (and currently) disinvested and disenfranchised low-income residents in their communities.

We have written this article to help those managers and their staff who are grappling with this issue in their organizations, want to understand the systemic nature of racism in their communities and organizations, and want to implement the kind of internal change that needs to happen to create racial equity.

It has been over five years since the city of Evanston started its work in racial equity and we are just now heading down a path that will move the organization forward to operationalize equity. There are many communities like Evanston who struggle with how to actually make racial equity “stick.” Now is the time to address this problem directly and to offer some perspective and a working solution to this foundational problem.

In this article, we will first offer a brief analysis of what is holding back efforts to implement racial-equity-driven change within local government and one possible path forward. It should be made clear that we applaud all federal efforts to keep this topic front and center on the federal level, such as the recent executive order, “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government.” At the same time, our goal is to make the case that the place where this work must “stick” is across the thousands of local governments that have a direct and meaningful impact on the health and well-being of their communities. We will show how the institutionalization of racial equity analysis and approaches inside government processes can be done, and how that actually improves organizational performance through a culture shift that values diversity, equity, and inclusion in clear operational terms.

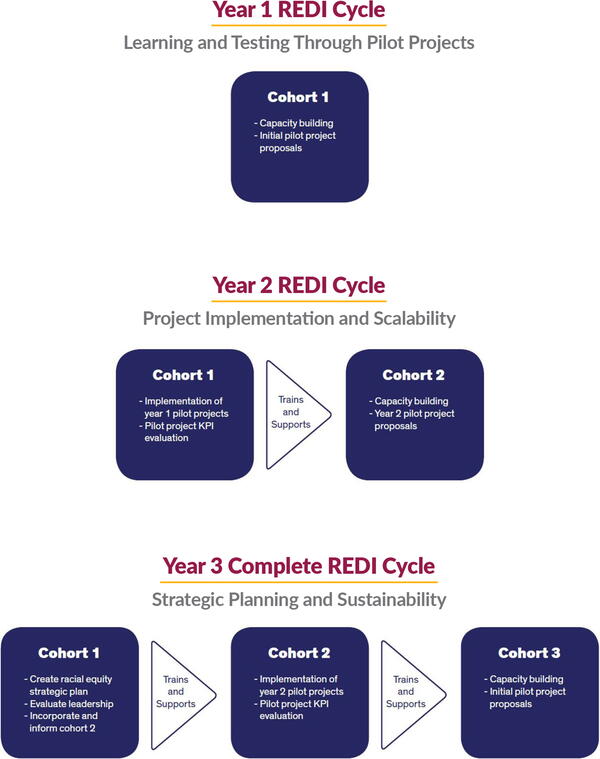

The model we will share is called the REDI Model (an acronym of “racial equity, diversity, and inclusion) and emphasizes individual skill and team building centered around four key areas: project management, policy analysis, process analysis and change management, and socio-emotional learning and emotional intelligence. This model was co-developed by Dr. Kathleen Yang-Clayton and over 50 public leaders and staff from two mid- to large-sized public organizations over the past three years.

The unique aspect of the REDI model is its focus on individual and team-building skills that are centered around learning about racial equity and applying these concepts to central administrative and managerial functions of organizations such as human resources, operations, planning and evaluation, and procurement. We will then illustrate this model with concrete examples implemented in Evanston, where we applied a version of this model for a short-term challenge and then leveraged the success of the model to launch a city-wide effort that is currently in its first year.

What Is the Problem?

There are two problems with the way racial equity has been applied to local government issues. First, there is an enormous amount of confusion about the term itself and at what level it should be applied. While this could be a whole other article in and of itself, for the sake of getting to some working solutions we will simply state our working definition and why it is relevant to understanding the foundational purpose of the model we present. Racial equity is not just about race. In other words, we use the term race before equity not to tribalize or divide, but to acknowledge a core analytical and historical reality that strengthens our approach to more viable and impactful solutions. When we avoid the use of the term race, we weaken our own analytical approach. Also by omitting race before equity, we can easily fall into the trap, once again, of failing to acknowledge the prior harm that local, state, and federal governments have perpetrated on African Americans and indigenous tribes since the founding of this country, and continue to reimpose on women, immigrants, and those with disabilities, as well as the LGBTQ+, veterans, and low-income rural communities. Thus racial equity is both (1) acknowledging these prior harms that our institutions have perpetrated on broad swaths of our country and (2) taking action to reallocate our collective resources to target support to those members of our communities who need more assistance and a sense of belonging to something bigger than their individual needs. In order to do this, we must elevate the performance of our local governments for all residents and that vision requires a commitment to internal organizational change that is often overlooked in this work.

Second, there is a tendency to emphasize external and not internal change. By simply jumping to the external examples that can be done in a short period of time and not committing to the deeper, slower, and more transformative work needed within our local government organizations, we continue to ignore the lack of investment in the human capital of local government employees and staff needed to reinvigorate and meet the skills required for twenty-first century governance challenges.

In addition, broadly speaking, there are two relevant levels at which we can think of how racism affects all of us. The first is the individual level, where internalized and interpersonal racism exists. Implicit bias training provides pathways for individuals to recognize and address these individual level issues. The second level is structural racism, which can be seen in both the individual institutions and entire systems of institutions we have in our country. It is this second level that is the focus of our work, which identifies institutionalized racism in the everyday standard operating procedures (SOPs) within public governments. As many of you know, SOPs exist across all areas of practice in local government. For many of these SOPs, most of us who now labor under some of their more esoteric rules do not recall why they were written in such a way or what their original intent may have been, but we have all suffered under the administrative burden of realizing the harmful consequences of these SOPs in our everyday work. Dismantling and building new structures of inclusion and SOPs that provide the clear guidance and accountability needed for administrative practice is the purpose of our racial equity efforts.2

What Is the REDI model? How Does It work?

Let’s say that you have made the commitment to operationalizing racial equity within your organization. How do you get started? Before we get into the nuts and bolts, there are some context issues you should keep firmly in mind.

First, institutional racism did not happen overnight, nor will the solutions be implemented overnight either. If you do not see a clear path to commit to a three-year organizational change process, or even a six-month pilot application of this model, then you should pause and wait until the surrounding environment for your vision is more welcoming.

Second, we must acknowledge that the political pressures placed on managers and staff to respond to immediate events and needs of elected officials often places all of us in a “hurry up and wait” pattern of program and planning delivery that leaves very little room for the kinds of participatory and deliberative practices that are the engine of racially equitable organizations. We recognize this challenge and acknowledge that the burden falls on managers to navigate the urgent and important everyday management issues with their strong personal commitment to racial equity and organizational performance improvement.

Knowing when the REDI model is a good fit for your organization can be challenging because of the complexity of each organization, but this is a simplified checklist to determine organizational readiness:

- External pressure to demonstrate effective implementation of racial equity principles to the core mission of the organization.

- Top-level leadership is fully on-board and open to a racial equity-driven organizational change model.

- Urgent need for mid-level staff to be trained so that there is shared understanding, vocabulary, and toolkits related to racial equity implementation.

- General desire to build collaboration and buy-in across all departments.

- Commitment to allocate resources to support this work.

There are three main components to the REDI model: content/training, recruitment, and impact/sustainability.

Content/Training

REDI members are provided the opportunity to cultivate critical skills needed to understand and implement racial equity pilot projects. Whether for the six-month or three-year models, the content does not change, but the depth of understanding and practice does.

Project Management:

- Learning new models of meeting planning and group project management.

- Identifying key performance indicators connected to core processes and racial equity.

- Train-the-trainer experience to scale the work of racial equity and create organizational sustainability.

Policy Analysis:

- Learning new applied research tools, such as interviewing and focus group analysis.

- Applying the racial equity impact analysis approach and results-based accountability in program and policy design.

Process Analysis and Change Management:

- Learning about the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle and pilot project testing and learning.

- Implementing new racial equity-driven process improvement.

- Experiencing a strategic planning process that assesses where racial equity work best fits into the existing and future organizational structure.

Socio-emotional Learning and Emotional Intelligence:

- Building relationships based on shared values and vision.

- Understanding the difference between individual- and institutional-level racism.

Recruitment

The recruitment of the initial REDI cohort members is highly dependent on the leadership of the organization. For the six-month model, the cohort is largely determined based on the project need. For example, for the city of Evanston, cohort members were selected from the six social service programs that were scattered across different departments. The city manager and deputy city manager were involved in the development of the cohort, and worked with them and their supervisors to ensure that they had the time to volunteer for the REDI committee. The members were drawn from mostly non-supervisory positions, although in the case of the six-month REDI, exceptions were made when a supervisor or director was personally supportive of the creation of the committee and had direct experience in the program areas that were to be analyzed.

Impact/Sustainability

For the six-month REDI model, focusing on impact and delivery of a single policy proposal was the goal. For the three-year model, we also build in processes so that the organization can sustainably reproduce basic racial equity training for new cohorts without external support. By impact, we mean that REDI committee members identify pilot projects that address internal constraints and organizational culture perceived to limit achieving racially equitable outcomes for the community within and outside of the organization. By a series of internal and external focus groups and reporting out of findings and lessons learned, the REDI process also intentionally builds buy-in and models the transparency and accountability necessary to institutionalize racially equitable practices. For the three-year REDI model, sustainability past the initial engagement with university-based practitioners is an explicit indicator of impact and success for the model.

Case Study: Six-Month Social Services REDI in Evanston

In 2018, the city of Evanston began its annual budget process months earlier than usual to undertake a priority-based budget process (PBB), as Evanston faced budgetary challenges. This process allowed staff, city council, and the community to review all programs and services provided by the city prior to the creation of the 2019 budget. When the 2019 fiscal year began on January 1, 2019, 54 out 152 programs were up for consideration as part of the PPB process. Ten of the 54 programs were related to social services, which concerned many community members who saw this as a sign that these programs were being cut. The leadership of the city decided that before attempting to make any recommendations related to social services programs, it would implement a REDI process to incorporate key stakeholder perspectives and to identify alternative opportunities that took into account the needs of those who were served and the staff who served them.

Key issues identified included the siloing of social service programs and the awareness that these programs were critical to the communities acknowledged by the city as most marginalized and harmed by racial inequity over the decades. Racial-equity-driven questions were posed on how to increase organizational performance and to center the city’s mission to make Evanston the most livable city for all residents, especially those who have the most need.

The REDI approach made the case to focus on the internal environment and to work back out toward key stakeholders, which included the staff and leaders who provided the daily program services for seniors, at-risk youth, and low-income residents. We began by bringing a small team of social service staff together in an intentional arc of engagement and training that would empower them to lead a racial-equity-driven policy analysis that could co-create organizational options that would minimize harm to communities they served while seeking organizational performance improvements.

Through monthly training and applied project application between training sessions, REDI committee members learned about racial equity analysis within the context of public administration, concrete project management skills, facilitation skills, policy and process analysis, and socio-emotional learning practices. Once a strategic plan was created, REDI members learned how to facilitate meaningful feedback sessions with other relevant city staff, nonprofits involved in social service delivery, clients, and the general public. Importantly, this engagement was well in advance of any final policy proposal from the REDI committee. Input from these key stakeholders drove the identification of policy options instead of predetermined options being handed to the stakeholders to simply validate.

There were three major lessons from implementing the REDI model.

Lesson #1: Take the time to establish a clear sense of vision and mission.

Taking the time to create and validate a vision and mission for the committee was really important to clarify the committee’s purpose and establish a shared sense of purpose. Here is what was shared with internal staff after the committee finished their process.

Social Services Core Committee’s Shared Vision

- True belief in shared prosperity for Evanston.

- Decision making is driven by those who are most in need/impacted.

- All (residents + employees) feel a sense of belonging and ownership

- All departments work together seamlessly.

- High levels of trust among residents and employees in Evanston.

Social Services Core Committee’s Shared Mission

- Ensure that policy analysis is driven by a benefits/burdens framework through a Racial Equity Impact Analysis (REIA).

- Demonstrate that inclusion and trust among employees is critical to increasing the impact and effectiveness of government.

- Exclusionary hierarchies do not promote the insight and innovation needed to allow REIA to take root across all departments and levels.

- Change a process or program not based on the need to cut services, but on creating active structures of inclusion.

Lesson #2: Shift the mindset from defensive to asset-based engagement.

Too often city staff are sent out “into the community” trying to “sell” a policy or program that is in the final phase of approval or already been approved. They are also aware that the posture they will have to take is either defensive (e.g., defend the proposal) or simply compliance-driven (e.g., we need three community meetings before we go ahead and do what we were planning on doing). Instead, we trained REDI members on the basics of community-engaged research so they understood the critical role community engagement can play to improve their own analysis, which in turn would amplify their own professional success and sense of connection to the communities they serve. The basics of community-engaged research are still not taught as pervasively and rigorously as they should be in graduate programs for MPA and MPP students, but they are comprised of:

- Constructivist listening and identifying critical one-on-one meetings with key stakeholders.

- Creating and facilitating inclusive and generative community meetings.

- Supplementing quantitative data with qualitative data (e.g., gathering stories from stakeholders on what was actually at stake).

Lesson #3: Incorporate critical project management skills to staff toolkits.

We all acknowledge that one of the first things that gets cut from budgets are trainings that are not mandated by law. At the same time, many leaders and staff acknowledge that the lack of building and supporting a learning culture in government has caused fundamental problems in performance, implementation, and retention of high-quality staff. Within this context, we decided that enhancing project management skills would be essential to implementing racial-equity-driven projects. The key skills that were taught and applied consistently across the project were:

- Project accountability models that help team members clearly identify their roles and responsibilities on the team (e.g., DARCI model, MOCHA model).

- Short-cycle strategic planning (e.g., POP model).

- Understanding how to implement an iterative process of learning to avoid bias and incorporate consistency in the process to ensure the most accurate outcomes possible.

At the end of the six-month process, the Evanston REDI committee recommended realigning all social service programs under the department of health and human services (HHS). Programs that had been previously siloed in parks and recreation and the library were brought together, with an emphasis on cross-communication and coordination. The pandemic hit three months after the new department was formed, and many staff were inspired by their new ability to rapidly respond to crises hitting seniors, low-income families, and at-risk youth. For example, in response to growing food insecurity driven by the shut-downs, scaling up the capacity of the community food-pantry was done in a couple of weeks rather than months. Another example was how staff working with seniors and at-risk youth were more effective at navigating some of the complex screening processes for relief funds that were available through the city because they could work directly with co-workers who knew the system the best.

Long term, the city has initiated two more REDI-related efforts. The first is to revise their funding process for supporting social services by taking recommendations from the REDI committee. The outcome is for the city to set a clear direction and identify complementary service areas that nonprofits are uniquely qualified to provide. Second, the city has been able to leverage funding from external sources to support a city-wide REDI committee that cuts across all major departments and launches a three-year cycle of racial equity driven organizational change. There are currently four pilot projects that are tackling language access implementation, new manager training, access to education for staff, and prioritizing the request for services using a racial equity framework. Each project is testing assumptions by interviewing key stakeholders within the organization through a series of one-on-one interviews, focus groups, and online surveys. To note, external partners and community members have already been consulted about many of the issues that are being addressed by these pilot projects. Now is the time to build new structures of inclusion and performance inside of the organization.

Conclusion

The operationalization of racial equity is in the top five list of innovative or transformative visions for the twenty-first century, and it should be considered a prerequisite for any of those visions to yield a just, equitable, and democratic future—not just for residents, but for the planet as a whole. The community within governments and organizations must be revived and engaged with a mission that connects racial equity to organizational performance. In order to revive and engage our communities, we must take this historical moment and deeply transform the internal environment of local government.

Most importantly, we need leaders “at the top” who are committed to a vision of racial equity and democracy within our public institutions, managers who are ready and willing to dismantle dated internal processes that create barriers and marginalize staff, and for everyone inside of the organization to lean into building new structures of inclusion. There is a renewed sense of the mission of a strong, vibrant, and inclusive public sector. The way we implement and operationalize programs that are designed to uplift communities must acknowledge that centering racial equity into a vision of twenty-first century democracy addresses historical flaws and builds an inclusive future for all.

KATHLEEN YANG-CLAYTON, Ph.D., is associate dean of diversity, equity, and inclusion; and clinical associate professor of public administration, University of Illinois at Chicago. She is also a research fellow with the Great Cities Institute.

KIMBERLY RICHARDSON, MPA, is deputy city manager of Evanston, Illinois.

Endnotes and Resources

1 PM magazine has done an excellent job of raising the awareness and deepening the discussion of this issue among public managers. The efforts by the city of Renton address both external and internal efforts to implement racial equity in core services such as language access, public service access, community organizing, public events, police, and human resources ( PM magazine, “Engaging Our Community for an Equitable Future,” May 1, 2021). Other articles have focused on the challenges of implementing specific racial equity issues in policing ( PM magazine, “Transitions, Transformation, and Equitable Advancement,” February 1, 2021) or tackling broader issues around anti-racism (“Anti-Racism: The Responsibility of All City and County Managers,” (October 6, 2020); “Fostering Economic Inclusion, Social Equity, and Justice for People of Color” (June 24, 2020). We offer our article along the lines of “Racial Equity in Action: How to Get Started,” (October 1, 2020), where we try to explicitly detail out the logic and implementation of racial equity in a mid-sized municipality in the Midwest.

2 This may also require working with employee union organizations to make changes that were collectively bargained.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!