This is the sixth in a series of six articles about crime reduction. Links to the other articles in the series are listed at the bottom of the page.

Five Crime Fallacies

City and county managers hear hundreds of proposals for crime reduction. If applied, most of them will fail. Why?

Consider this example. Though hypothetical, it is very similar to actual events coauthor Tom Carroll experienced as a city manager. After a pair of killings outside of a nightclub with a history of shootings in a lower-income neighborhood, residents demand action. The mayor declares gun violence a public health crisis. The city manager demands that their police chief do something about it. The police chief quickly proposes to increase police patrols across the neighborhood. Community leaders exhort the residents to join an upcoming march against violence and form a committee that meets monthly. The police agree to host a community barbecue after the march. Over the next week, police increase enforcement and arrest several young Black men for minor crimes that are unconnected to the shootings. Then, within a few days, things return to normal. Within a short time period, the nightclub has additional shootings.

Why did this response to the killings fail? If you read our previous articles, you know. The decisionmakers applied strategies based on five fallacies about crime. Declaring a public health crisis applies the “solutions to crime are complicated” fallacy. The city manager’s instinctive demand for immediate action from the police chief applies the “police can solve all crime problems” fallacy. The police chief’s blanket strategy to increase patrols across the neighborhood applies the “crime is widespread” fallacy. The community march, committee, and barbecue applies the “residents matter most to reduce crime” fallacy. The stepped up police enforcement and arrests applies the “more arrests reduce crime” fallacy.

What could the city manager have done instead? A problem-solving effort in Anaheim, California, USA, suggests an answer. For more than 25 years, a nightclub was a thorn in the community’s side. Between 2000 to 2006, the club generated 2,534 calls for police service, an average of 500 calls per year. The nightclub accounted for the most calls for service of any property in the city. These calls included fights, intoxicated patrons, and traffic congestion.

Over time, club-related calls for police service escalated to rapes, drug use and dealing, stabbings, and shootings. Firearms seizures became routine. Nearby businesses complained even more that the nightclub was creating problems on their properties and in the immediate area: noise, vandalism, dining and dashing, drinking in cars in parking lots, speeding, driving under the influence and traffic collisions, fights, and firing weapons. Then in 2006, in two separate incidents, a patron shot and killed another patron near the club.

For years, several fallacies drove the Anaheim Police’s response. They increased police patrols and took a zero-tolerance enforcement approach hoping to arrest more people for crimes, particularly for traffic infractions and drinking and loitering in the parking lot. But this was costly; the police department was spending thousands on overtime. And the police department realized that “while all of these tactics generated large numbers of cites and arrests, most provided only short-term relief.”

The Anaheim Police were fed up with returning to the same place for the same problems; they were merely disrupting opportunities for crime. So, they adopted a strategy that dismantled the opportunities for crime. The police department began an investigation of the owners. They discovered a complex owner network of investors who were committing fraud and illegally profiting from the nightclub. They discovered that the nightclub was operating under the wrong liquor license. And they discovered the club was not following rules set under the business’s dance-hall permit.

The police contacted government and regulatory agencies about the club. The city threatened to revoke the club’s dance-hall permit. The state Alcoholic Beverage Control began pursuing a license revocation. Police also contacted agencies about suspected tax fraud and fraudulent bankruptcy filings: the Internal Revenue Service, U.S. Attorney and Orange County District Attorney, and State Insurance Department investigators. Foreseeing costly court proceedings, the nightclub owner surrendered his business license and dance-hall permit. He also sold his liquor license. The nightclub closed in 2006, and the city found new owners to redevelop the property.

These actions solved the problem. There was a dramatic decline in calls for service to the former club. Crime that had been radiating from the property declined; nearby business owners stopped complaining. And police overtime costs for patrolling the area disappeared. None of this would have occurred had the Anaheim police kept applying strategies based on crime fallacies.

Fallacies contaminate many crime strategies. So, how can you avoid them? Use the SCRAP test: a tool to identify and overcome crime fallacies.

The SCRAP Test

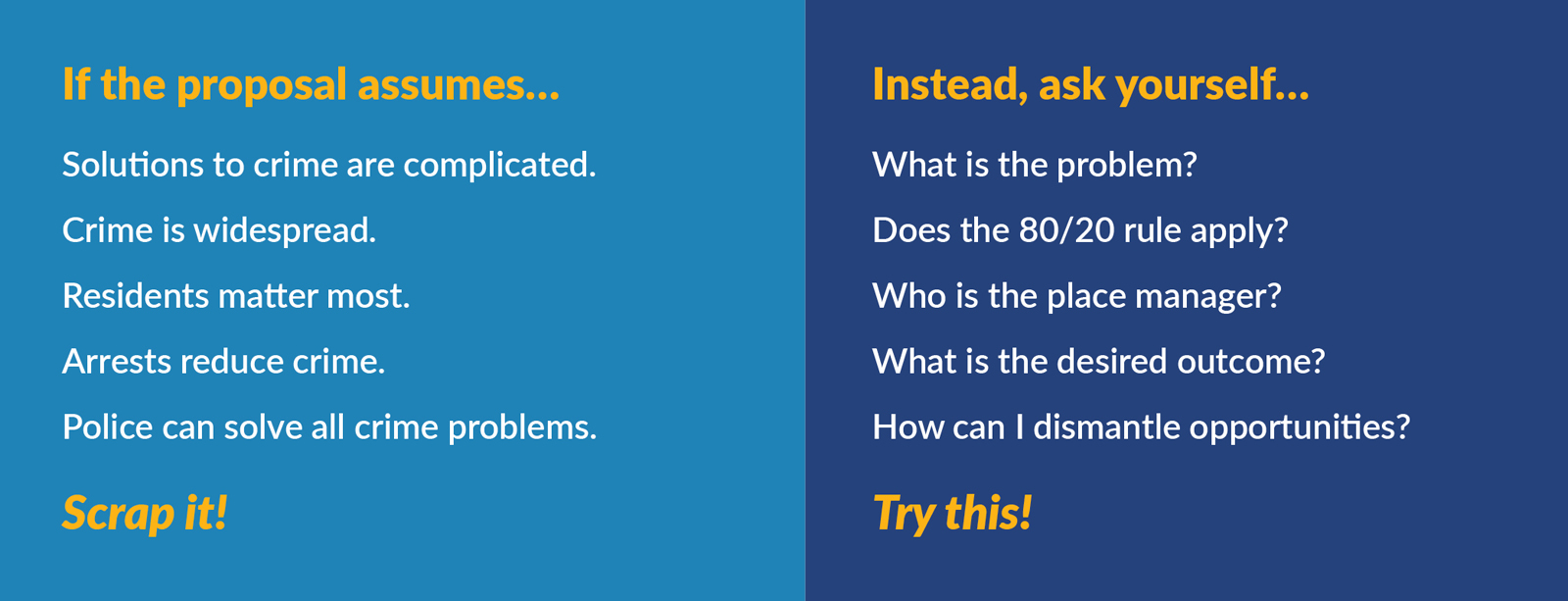

Crime reduction ideas applying these fallacies can come from anyone: local politicians, colleagues, residents, community activists, police, academics, business leaders, state and national legislators, the media, and others. Sometimes their proposals even sound plausible. Therefore, you have two needs: (1) a way to identify proposals that are based on fallacies, and (2) a way to adjust ideas to form effective crime reduction strategies. The SCRAP test, seen in Figure 1, addresses both needs. SCRAP is an acronym made from the first letters of the five fallacies. Here is how it works.

First, take any crime reduction proposal and ask yourself if the proposal applies any of the fallacies in the left (green) column. The more of the fallacies you check, the more likely the proposal will fail. Second, if the proposal applies most of the fallacies, you should “SCRAP” the proposal. Third, if the proposal only applies a fallacy or two, you can consult the right (blue) column. The right column shows how to adjust the proposal so that the strategy is more likely to succeed.

You can also use the SCRAP test to design a crime reduction strategy from scratch. First, use the right column to guide strategy design. Then, use the left column to check your strategy for fallacies.

Now that you’ve seen the SCRAP test, let’s apply it to our hypothetical and Anaheim Police examples.

Fallacy 1: Solutions to Crime Are Complicated.

In our hypothetical example, the mayor declared a public health crisis. Declaring a public health crisis sounds decisive, but it doesn’t help unpack the problem. Instead, the mayor should have asked: what is the problem? The Anaheim Police identified their problem: the operations of a single nightclub. Solutions to crime do not need to be complicated if you get to the source of the problem.

Fallacy 2: Crime Is Widespread.

In our hypothetical example, the police’s response was to patrol the neighborhood—a blanket approach. Instead, the police chief should have asked: does the 80/20 rule apply? The Anaheim Police applied the 80/20 rule. They focused on a single nightclub, not other nightclubs, the neighborhood, or city.

Fallacy 3: Residents Matter Most.

In our hypothetical example, the community organized a march and formed a committee, and the police hosted a barbecue. Instead, the police and community should have asked: who is the place manager? The Anaheim Police identified the people responsible for creating the crime opportunities: the owners and investors of the nightclub.

Fallacy 4: Arrests Reduce Crime.

In our hypothetical example, the police increased enforcement and arrests of people unconnected to the nightclub shootings. Instead, the police should have asked: what is the desired outcome? The Anaheim Police identified their desired outcome: to reduce violent crime and calls for service.

Fallacy 5: Police Can Solve All Crime Problems.

In our hypothetical example, the city manager demanded that the police act. Instead, the city manager should have asked: how can we dismantle crime opportunities? The Anaheim Police prompted investigations by federal, state, and local agencies and redevelopment work by the city. Those agencies had the power to compel the owners to change their business practices and shift the property to productive uses. You cannot shift a property toward productive uses without getting the owners involved.

We’ve used a hypothetical example and a retrospective application of the SCRAP test. How can you apply the SCRAP test in practice?

The Fort Myers Police Department SCRAPs Bad Ideas

In 2016, wanting to reform its police department, the city of Fort Myers, Florida, USA, turned to an outsider, Derrick Diggs, to lead their department. Chief Diggs, along with a group of consultants, including coauthor Dan Gerard, worked to identify major crime concerns in the city. Violent crime was one of its primary concerns.

Like every other city, crime in Fort Myers was highly concentrated; 40% of all property crimes occurred in less than one square mile of the city. Like most cities, residents and city officials demanded traditional police responses (arrests, increase patrols, and community-oriented policing) to address the city’s crime.

At the suggestion of Gerard, Chief Diggs incorporated the SCRAP test into the police department’s strategic plan. Internally, the chief used the test to convince command staff officers to think beyond police patrols to reduce crime. The test prompted officers to think about problem-solving with place managers at the few places driving most of the crime. The test also helped identify officers who understood how to put evidence-based strategies into practice. Externally, the chief used the test to facilitate discussions with government officials and the public as to why certain policing strategies are unlikely to reduce crime, despite sounding plausible in theory.

As the police department applied the SCRAP test to more and more problems, they were able to develop targeted anti-crime strategies. Six years after Chief Diggs began, researchers examined how well his department’s efforts worked. Violent crime dropped by 51%: homicides were down 40%, rapes were down 29%, robberies 59%, and aggravated assault by nearly 51%. In addition, property crime declined by over 21%. These declines were despite a nearly 33% increase in population. And during the same period, arrests dropped by 1,037—a 25% decrease.

Caveats to the SCRAP Test

We recognize that there is a whisker of truth to each of the SCRAP fallacies. First, major societal issues do contribute to crime. But these issues exist at such a large scale that no city or county manager, police chief, or group of residents will solve them. However, problem solving can produce tangible results in a reasonable time.

Second, though a few places experience most of the crime, some crimes are scattered about. Even a place with one call for police service deserves attention from the police. Sometimes people need momentary assistance from the police. But if problems do not recur, there is little need to engage in problem-solving efforts.

Third, residents do matter. However, they matter in ways different from what most assume. Residents can bring problems to the attention of police and local government. They can also impose strong political pressure to compel action from local government. But residents alone can seldom solve crime problems, particularly if the crimes in question are occurring on a property the residents do not own or control.

Fourth, arrests can be a useful tool. They allow the police to remove prolific offenders from the street. But there are few people that this applies to, so arrests should be used sparingly. Arrests are one of many tools to achieve safety; they are not the goal.

Fifth, police can do a great deal. But they are more effective when they partner with the people who have the legal authority to solve problems. Police, for example, can accelerate cooperation from various government organizations to solve problems at high-crime locations. Police can also work to convince place managers to solve problems on their properties.

Last, when high profile events occur, you may need to act quickly. Usually, your immediate response will not be problem-solving. But while taking immediate action, start a problem-solving process that can give your community long-term relief. Band-aids are useful, but eventually you need to actually solve the problem. A strategy inspired by the right column of the SCRAP test is more likely to do this.

SCRAP Bad Ideas

City and county managers hear hundreds of proposals for crime reduction. Since local governments are never over-staffed or over-funded, their managers need to weed out the many bad ideas they encounter and cultivate ideas that can succeed. The SCRAP test provides a quick and effective way to do this.

SHANNON J. LINNING, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada. She researches place-based crime prevention and problem-oriented policing.

TOM CARROLL, ICMA-CM, is city manager of Lexington, Virginia, USA, and a former ICMA research fellow.

DANIEL GERARD is a retired 32-year veteran (police captain) of the Cincinnati Police Department, USA. He currently works as a consultant for police agencies across North America.

JOHN E. ECK, PhD, is an emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Cincinnati, USA. For more than 45 years, he has studied police effectiveness and how to prevent crime at high-crime places.

Other Articles in This Series

Part 1: Do Solutions to Crime Need to Be Complicated?

Part 2: Is Crime Widespread?

Part 3: Do Residents Matter Most in Reducing Crime

Part 4: Do More Arrests Reduce Crime?

Part 5: Can the Police Solve All Crime Problems?

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!