This is the fourth in a series of six articles about crime reduction. Links to the other articles in the series are listed at the bottom of the page.

Where Should Your Focus Be?

Imagine this scenario, based on true events: An intoxicated driver kills a mother and child in a vehicle collision. The event leads to residents packing the next city council meeting. They line up at the podium to demand action, usually to “get tough on crime” and hire more officers.

The city manager and police chief agree to increase patrols, ramp up publicized sobriety checkpoints, and authorize overtime. They also pledge to assign a community liaison officer to visit all licensed bars and alcohol-selling stores to assess their safe serving and selling practices.

In a subsequent council meeting, the city manager reports that there has been a reduction in arrests for intoxicated driving, a reduction in crashes involving intoxicated drivers, and a reduction in hospitalizations linked to collisions.

Residents question the city manager as to why arrests have gone down and why they have not seen any additional officers patrolling in their neighborhood. Some residents accuse the police of not taking intoxicated driving seriously. Should residents be upset? Did the police fail?

Stories like this are common. Faced with a crime problem, many people leap to increasing arrests and hiring more officers as the solution. City officials often acquiesce. Complying with such requests can demonstrate sympathy but it rarely solves the problem. There often are more effective tools to reduce crime. In this article, we will show why arrest- and hiring-fixations blind people to alternatives that work better.

What Will Solve Your Crime Problems? Focusing on Outcomes.

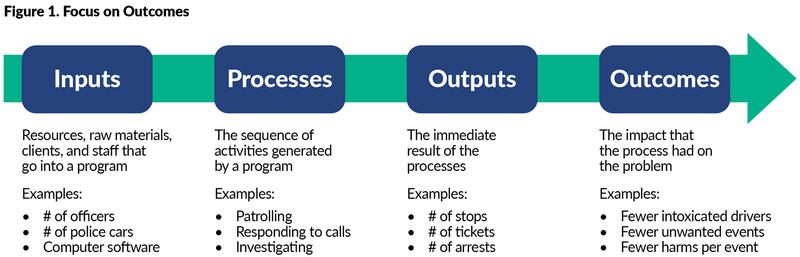

The residents in our example fell into a common trap: they focused on the wrong parts of the crime prevention process. Let’s break down the process into four parts: inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes (see figure 1).

Inputs are the things you use to produce outcomes. This includes hiring more officers, officer salaries and benefits, buying equipment for the police department, fuel for police cars, information technology, and so on. The processes put those inputs to use. In our example, processes included meeting with the employees of alcohol-selling establishments and carrying out sobriety checkpoints.

Processes produce outputs. In policing, this often includes the number of arrests made, community meetings attended, tickets issued, successful prosecutions, and so on. Outputs are not indicators of success; although occasionally they indicate that the process is working. But many outputs produce costs. Vehicle stops, for example, interrupt people’s lives, thereby producing a cost. The number of community meetings may produce benefits, such as increased trust in the police, but this is done at the cost of the time participants could have spent doing other things.

Outcomes are the impacts that the outputs have on the problem. In our example, the desired outcome was a reduction in crashes involving intoxicated drivers and the reduction in hospitalizations linked to collisions. Usually, outcomes can be described as reductions in harmful events—the events that infuriate the public.

In our example, rather than keeping their eyes on the reduction of crashes, injuries, and deaths averted, residents fixated on the number of arrests. But arrests are an output, not an outcome. It is possible that the liaison officer who worked with place managers of alcohol-selling businesses successfully reduced the number of intoxicated people getting behind the wheel. If true, then fewer people are driving while intoxicated. And if fewer people are driving while intoxicated, then fewer people are eligible for arrest. This means the police achieved their goal of fewer crashes, injuries, and deaths (outcomes) while simultaneously reducing the number of arrests (an output).

Another reason arrests should not be the goal is because crime is highly concentrated. We discussed this in our second article. While only a few places experience most of a city’s crime, there is also a concentration of offending; only a tiny fraction of people commit crime. A systematic review of 73 studies found that “the most active 10% of offenders account for around 41% of crime.”

The offender concentration becomes even more pronounced when you look at violent crime. In Fort Myers, Florida, USA, for example, 0.3% of the city’s population were responsible for 67% of the city’s homicides and non-fatal shootings between 2012 and 2017.1 In Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, 0.3% of the city’s population committed 75% of the city’s homicides between June 2006 and June 2007.2 Thus, devising strategies to increase arrests is misguided. Instead, your officers should focus arresting only the tiny fraction of people committing most of the crime.

Arrests continue to be a focus of the public, politicians, and administrators because they are easy to count. At best, arrests indicate “something” was done but they do not show that the right thing was done. You need to look beyond arrests. A similar logic explains why hiring more officers is unlikely to reduce crime.

Will Hiring More Police Officers Reduce Crime?

Following significant crime events, politicians often pledge to hire more police officers. This too usually has no impact on crime. Why? Because hiring more officers is an input, not an outcome.

Dr. YongJei Lee and colleagues sought to answer the question, does hiring more officers reduce a city’s crime rate? They published a systematic review of the 62 police force size studies conducted between 1972 and 2013. They discovered that the studies were wildly inconsistent. Thirty-two studies suggested that adding officers to a police agency reduced crime, while 30 studies found no evidence for the relationship. When they combined all the studies, and adjusted for study quality, they found that adding police officers had a miniscule and statistically insignificant impact on crime. When they compared the impact of hiring on crime to the impact on crime of other strategies, adding police was the least useful. Policing strategies such as problem-oriented policing, hotspot patrols, focused deterrence, and even neighborhood watch were far better at reducing crime than increasing a department’s number of officers. In short, the strategy of the police department matters more than the size of the department.

What explains these results? A likely answer lies in the economics principle of diminishing returns. This is the idea behind the expression, “too many cooks in the kitchen.” The concept predicts that the usefulness of hiring extra workers declines as more workers are hired.

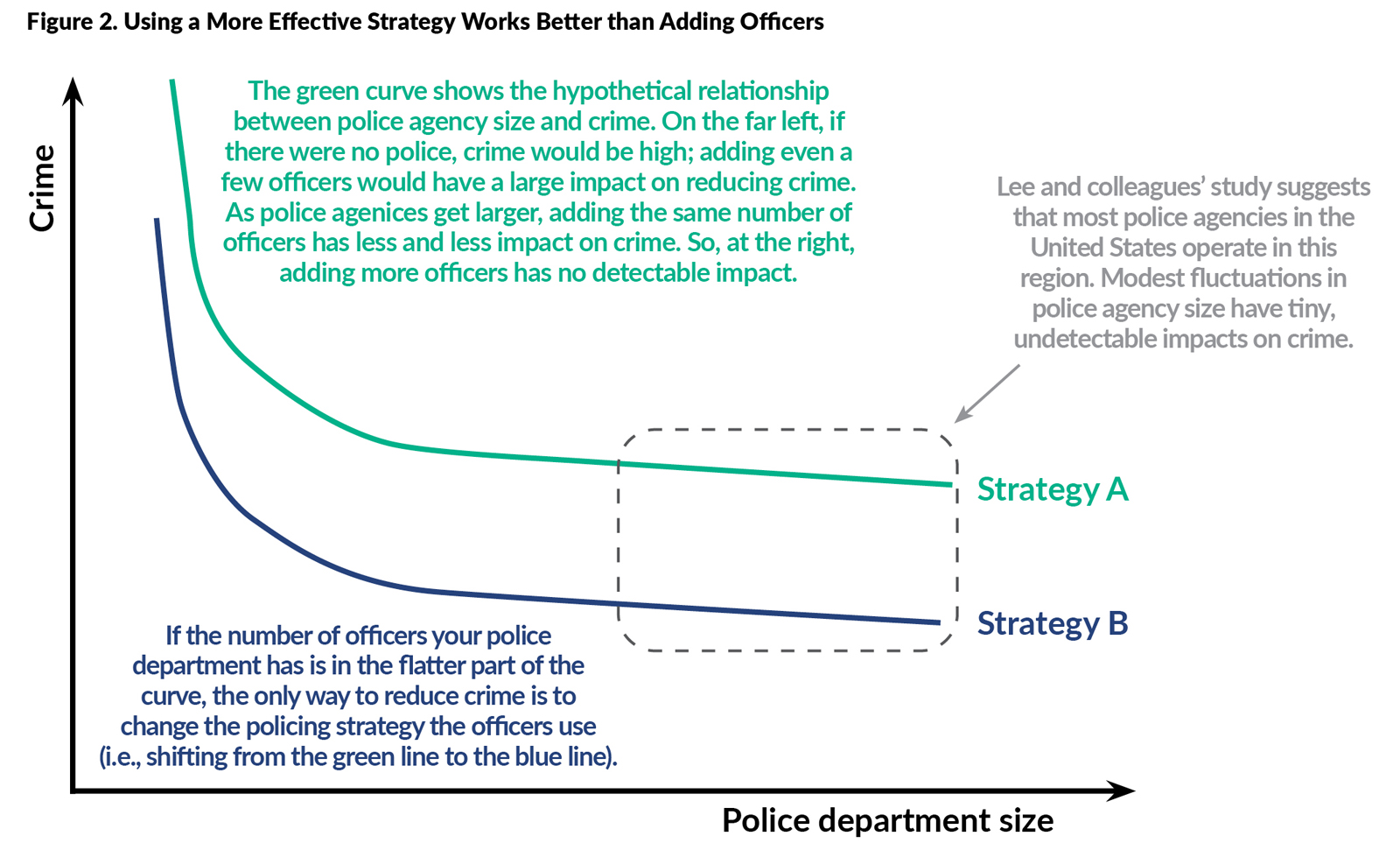

Policing is no different. If your city had zero officers, crime would likely be out of control. Then if you went from zero to 25 officers, you’d likely see a big drop in crime (left portion of the graph in Figure 2). But as you add officers, the benefit of hiring more officers levels off (right part of the graph in Figure 2). In Lee and colleague’s systematic review, the results suggested that most police agencies in the United States operate in the region denoted by the gray box. Adding a few officers to agencies in this region would see little noticeable benefit.

Take Cincinnati, a city of about 310,000 people, as an example. Their police department has about 1,000 sworn officers. If the mayor pledged to hire 10 more officers (incurring an estimated cost of over $1 million), this would only be a 0.9% change in police department size: too small to influence crime.

Whereas the Cincinnati example depicts a minor fluctuation in officers, what happens when you have a big change? Eric Piza and Vijay Chillar show this in their study of two similarly sized neighboring New Jersey police departments. Following the 2008 U.S. recession, the Newark Police Department laid off 13% of its department (167 officers). Newark experienced significant increases in property and violent crime after layoffs. By contrast, Newark’s neighbor, Jersey City, did not lay off any police and did not experience an increase in crime. So big changes in police force size can make a big difference.

Piza and Chillar note, however, that the layoffs forced the Newark police department to also abandon its hotspots policing strategy. The police department retreated to using its remaining officers for large area patrols and responding to calls for service. Thus, the change in strategy, due to the layoffs, probably contributed to Newark’s rise in crime.

Returning to our question about whether you should hire more police officers to reduce crime, the answer is it depends. If you have millions of dollars in your budget to hire a substantial number of officers, then this may be fruitful. But if you only have the capacity to hire a few officers, this would be a dubious method to reduce crime. Instead, apply effective strategies that reduce crime (i.e., change from Strategy A in green to Strategy B in blue in Figure 2). And tailor hiring decisions to the needs of these strategies.

Conclusion

We titled our article with the question, do more arrests reduce crime? Our answer is no.

When a sensational crime happens, residents demand action. Often someone will cry for more police and more arrests. As we described, neither approach is likely to be helpful because they focus on inputs and outputs, respectively, but fail to focus on reducing harms (an outcome).

Instead, ask yourself, what is the desired outcome? You need to identify and evaluate the outcomes you want officers to achieve. Improving outcomes requires that you adopt strategies capable of reducing crime-related harms.

What strategies should police use? In our next article, we show that when officers are problem-solving with place managers to dismantle crime opportunities, they achieve the desired outcome of reducing crime.

SHANNON J. LINNING, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada. She researches place-based crime prevention and problem-oriented policing.

TOM CARROLL, ICMA-CM, is city manager of Lexington, Virginia, USA, and a former ICMA research fellow.

DANIEL GERARD is a retired 32-year veteran (police captain) of the Cincinnati Police Department, USA. He currently works as a consultant for police agencies across North America.

JOHN E. ECK, PhD, is an emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Cincinnati, USA. For more than 45 years, he has studied police effectiveness and how to prevent crime at high-crime places.

Endnotes and Resources

1 Engel, R.S., Baker, S.G., Tillyer, M.S., Eck, J.E., & Dunham, J. (2008). Implementation of the Cincinnati initiative to reduce violence (CIRV): Year 1 report. Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati Policing Institute.

2 Haberman, C.S., Desmond, J.S., Gerard, D.W., & Henderson, S.M. (2018). Fort Myers Gun Violence Reduction Initiative Gang Activity: Year 1 report. Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati Institute of Crime Science.

Other articles in the series:

Part 1: Do Solutions to Crime Need to Be Complicated?

Part 2: Is Crime Widespread?

Part 3: Do Residents Matter Most in Reducing Crime

Part 5: Can the Police Solve All Crime Problems?

Part 6: How Can You SCRAP Crime Proposals that Are Likely to Fail?

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!