This is the first in a series of six articles about crime reduction. Links to the other articles in the series are listed at the bottom of the page.

The Importance of Crime Opportunities

German motor vehicle safety legislation once taught us a big lesson about crime. Between 1976 and 1985, Germany’s federal government rolled out laws requiring all motorcyclists to wear helmets. Their intent was to reduce harm to motorists if they were involved in a crash.

But something unexpected happened once they passed the laws; thefts of motorcycles plummeted. The laws also had no impact on other motor vehicle theft. Why?

Before the government passed the laws, thieves could ride away on stolen motorcycles without looking suspicious. But once the helmet legislation took effect, non-helmet riders stood out and faced an increase in their risk of getting stopped by the police. Drivers of other vehicles, like cars and trucks, did not stand out because they are not expected to wear helmets.

Many thieves stole motorcycles for joyriding. Thieves seldom went about their lives carrying around helmets on the off chance they would feel the urge to steal a motorcycle. So their options became (a) steal a motorcycle without a helmet and risk getting pulled over by the police, or (b) stop stealing motorcycles. Many would-be thieves chose the second option.

This motorcycle theft example illustrates three facts about crime. First, people are more likely to commit crime when it is easy. Researchers consistently find that when easy crime opportunities exist, people commit more crimes. Second, you are more likely to reduce crime when you influence how a crime is committed (the opportunity) as opposed to why the crime is committed (the motivation). Third, small and simple changes can have a big impact on crime. Researchers have found that when people problem-solve on a small scale and dismantle crime opportunities, they have the biggest impact on crime.

But if solving crime can be so simple, why don’t we do it more often? One reason is that most people think about crime incorrectly. They think crime is complicated and that reducing crime requires changing major societal conditions. As city managers, you’ve probably heard the public’s demands following a significant crime: You need to address the mental health crisis! You need to end poverty! You need to increase drug enforcement! You need to legalize drugs! You need to hire more police officers! You need to defund the police! You need to get rid of guns! We need more guns! And nothing changes. Then another significant crime occurs.

If you’re fed up with repeated crime crisis management, we have some evidence-based alternatives for you. This article is the first in a series dispelling common myths about crime. The first myth is that solutions to crime are complicated. The purpose of this article is to help you see through this myth so you can reduce crime by solving problems. Subsequent articles will deal with four other myths that often prevent local government officials from reducing crime. Our last article links the five myths and introduces a tool that identifies failure-prone crime strategies.

How Should You Think About Crime? Focus on the Problem

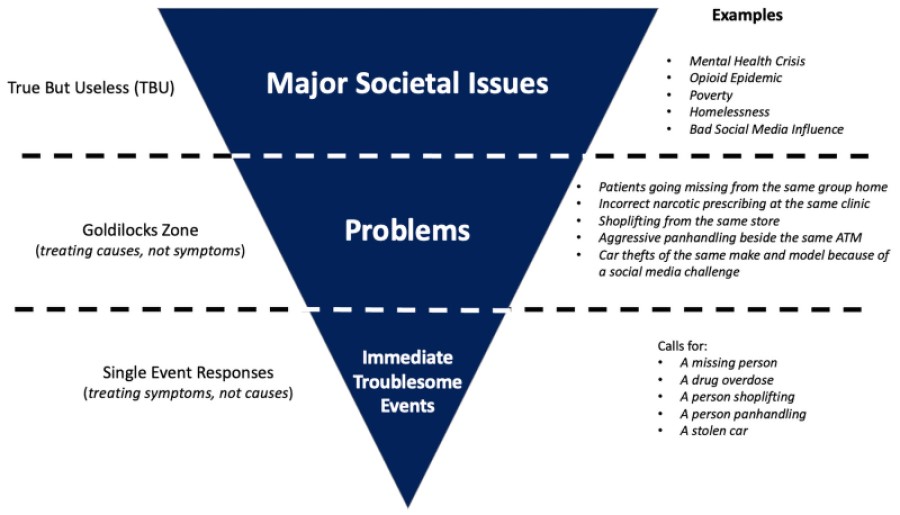

People tend to make two mistakes when thinking about crime. Their solutions are either too big or too small. Cries for action from politicians, the media, and the public are often too big. They usually center on solving major societal issues, such as homelessness, poverty, the opioid epidemic, the mental health crisis, and the like. To address these, you need widescale cooperation from bureaucracies and immense resources to tackle them.

The other mistake is the reverse; people tend to think too small. We often observe this in police departments whose strategy is either responding to 911 calls or putting “cops on dots” of a crime map. These are calls to address immediate troublesome events: a man yelling in the street, a woman overdosing in a park, a shoplifter stealing clothing from a store, or a thief breaking into a car in a parking garage. Simply responding to these requests makes officers feel like hamsters in a wheel running endlessly from call to call. Hiring more officers to chase these calls doesn’t prevent future events either. Police must keep going back.

While major societal issues and immediate troublesome events are problematic, they are not problems. To reduce crime in your community, you need to find the goldilocks zone between these two categories: problems.

Problems are a collection of unwanted or harmful events that need solving. Problems are patterned, not random, so they must recur and do so in a predictable manner. If there is no pattern, there is nothing to be solved or prevented. The patterns themselves reveal the true causes of problems. Problems are troublesome circumstances bigger than individual events, but smaller than bad socioeconomic conditions.

Figure 1 shows three ways you can think about crime. They are depicted in an inverted triangle to represent the scale of each issue. If you focus on problems, you’ll see faster progress and generate long-term results. These successes will also give you momentum to continue your problem-solving efforts.

Finding the goldilocks zone requires a little thinking. To illustrate, consider a concern that cities/counties consistently deal with: shoplifting. Motivations for shoplifting vary and epitomize several major societal issues. Some people steal because they have little money (poverty). Others steal because they need cash for drugs (the opioid epidemic). Others may shoplift simply for the notoriety (social media). While we are in favor of eradicating poverty, the opioid epidemic, and bad social media, as international development practitioner Jerry Sternin says, these solutions may be “TBU: True But Useless!” No police officer, mayor, city/county manager, or citizen will be able to accomplish them alone, and especially not quickly.

Shoplifting materializes as an immediate troublesome event every time retailers call the police. If a store experiences a single shoplifting event, no action is needed. But if a single store experiences many shoplifting events, you have a pattern. A common strategy is for police to simply respond to the immediate troublesome events every time they receive a call. But if you’ve identified a pattern, it also means you have identified a solvable problem. If you solve the problem, the officers will not have to keep going back.

Crime analyst Michael Zidar and his team identified a problem when analyzing shoplifting patterns in Paducah, Kentucky, a Midwestern U.S. city of approximately 25,000 residents. Looking at police reports, Zidar discovered that the city’s two Walmart stores represented 15.1% of all police reported crimes and 67.4% of all shoplifting reports in the city. So, in theory, if they could eliminate shoplifting at only two stores in the city, they could reduce shoplifting in the entire city by two-thirds.

There are many ways to reduce shoplifting in a store. Stores who choose to install self-checkouts are at a higher risk of shoplifting, for example. A store can choose not to install them or remove them if present. Similarly, retailers can install locked display cabinets for high-value goods. They can also install a register next to the goods requiring customers to pay for high-value goods immediately instead of waiting until they get to the front of the store to buy them.

In Zidar’s Walmart case study, the two stores were unwilling to implement any of the evidence-based suggestions the police provided to reduce shoplifting. So, the police department implemented an online crime reporting system for any non-violent/compliant misdemeanor shoplifting cases at the two stores. The police department would no longer send officers to the stores when a customer tried to shoplift goods worth less than $500. This shifted the financial burden of crime prevention from taxpayers to the stores themselves. This strategy led to a 45.2% reduction in shoplifting that the city had to deal with: an annual savings of about $27,000 in police time.

Say CHEERS to Your Problems!

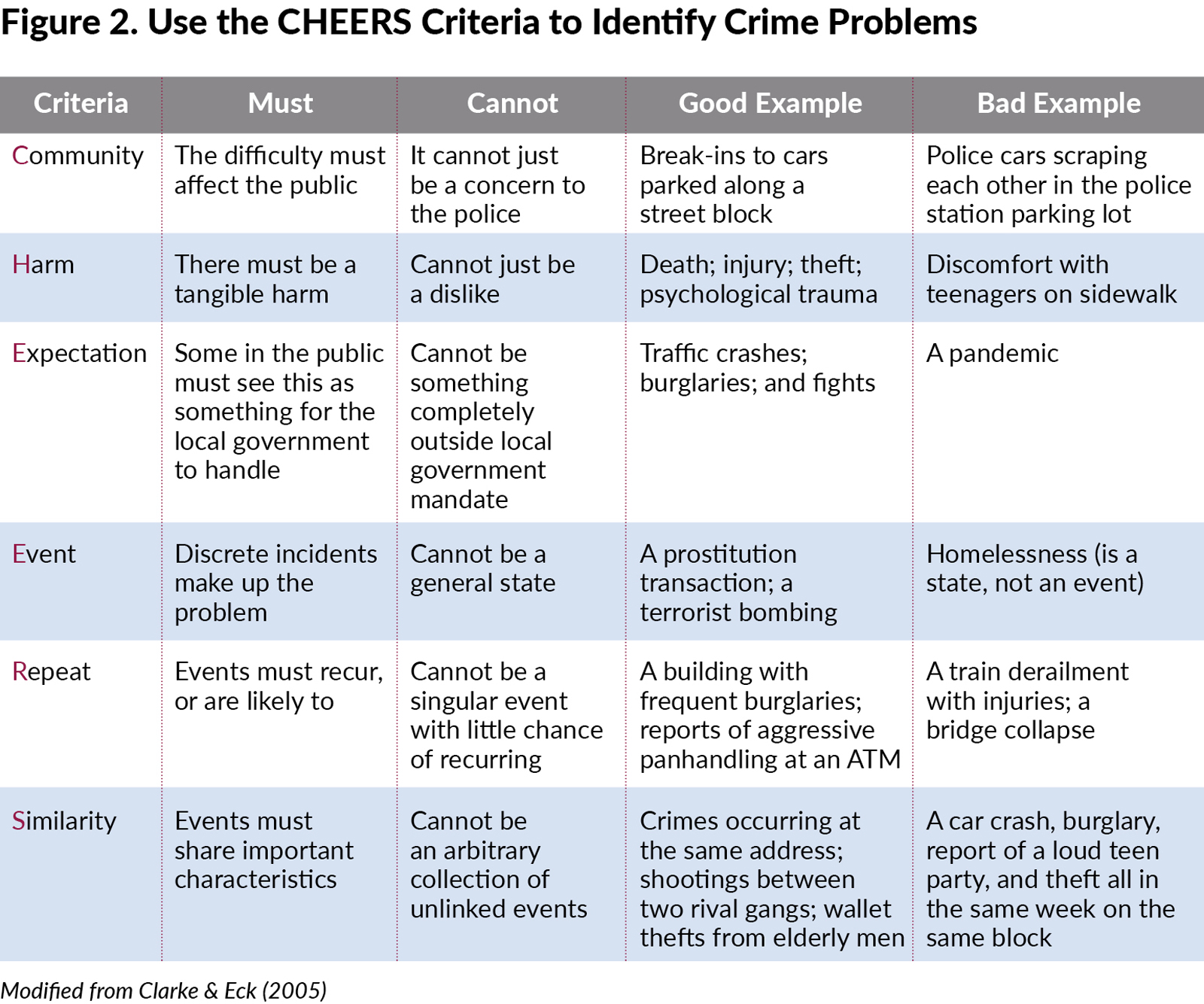

We have advocated for focusing on problems, but how do you know when you have a problem? One way to identify crime problems is to use a modification of the CHEERS criteria, created by crime scientists Ronald Clarke and John Eck. CHEERS is an acronym that represents the six components of crime problems (Figure 2).

First, the concern being described must occur in the community. It cannot be a concern solely for local government administrators, such as police officers not wearing their hats. Second, there must be something harmful happening: death, injury, taking or destroying something that belongs to someone else, or even fear of using public space. It cannot be just a state of being, such as homelessness or something that makes people uncomfortable, such as teenagers standing on a street corner as you pass by. Third, there must be some expectation among some members of the public that local government must be involved.

Fourth, all problems involve events, such as break-ins, threats, or transactions. It cannot be general states such as poverty or racism, or other general conditions like stupidity or declining morals. Fifth, the events need to repeat or have a high likelihood of repeating. If something is unlikely to recur (like a meteor strike), then there are no future events to prevent. Finally, these events that repeat must have something in common, a basis of similarity that indicates a common set of causes. They cannot be an arbitrary set of unconnected, albeit unfortunate, events.

Anything that does not meet all six CHEERS criteria is not a crime problem, in the technical sense. But if all six criteria are met, you can consider it a crime problem and begin your problem-solving process to understand why crime is occurring (covered in our next article).

Conclusion

We titled our article with the question, do solutions to crime need to be complicated? Our answer is no.

If you focus your efforts on major societal issues, you probably won’t get very far, and you’ll likely waste a lot of time and money. If you focus your efforts on immediate troublesome events, you probably won’t get very far either. Your police department will spend their time responding to 911 calls that simply address symptoms of underlying problems. They’ll keep having to go back to the same places about the same concerns.

Instead, ask yourself, what is the problem? Solving problems in your city/county will reduce crime. And as we will demonstrate in our next article, these problems will repeatedly occur at a tiny fraction of your city’s properties. If you can dismantle the crime opportunities at those few places, you will reduce your crime rate.

SHANNON J. LINNING, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada. She researches place-based crime prevention and problem-oriented policing.

TOM CARROLL, ICMA-CM, is city manager of Lexington, Virginia, USA, and a former ICMA research fellow.

DANIEL GERARD is a retired 32-year veteran (police captain) of the Cincinnati Police Department, USA. He currently works as a consultant for police agencies across North America.

JOHN E. ECK, PhD, is an emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Cincinnati, USA. For more than 45 years, he has studied police effectiveness and how to prevent crime at high-crime places.

Other articles in the series:

Part 2: Is Crime Widespread?

Part 3: Do Residents Matter Most in Reducing Crime?

Part 4: Do More Arrests Reduce Crime?

Part 5: Can the Police Solve All Crime Problems?

Part 6: How Can You SCRAP Crime Proposals that Are Likely to Fail?

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!