This is the third in a series of six articles about crime reduction. Links to the other articles in the series are listed at the bottom of the page.

For years, police officers in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, had a thorn in their side: the Klondiker Hotel, one of three hotels along a business strip. Residents complained that the property was riddled with crime problems, such as prostitution, drug sales and use, public intoxication, assaults, and knifings on or near the property.

The usual police responses did not work. Arrest-focused strategies caused a temporary dip in criminal activity, but crime always returned. Community-oriented policing strategies uncovered information from residents but did not provide solutions. Were there any alternatives?

Police identified the hotel’s owners. They were absentee owners who paid little attention to how the property was being managed. The police informed the owners about the corrupt staff who were facilitating criminal activity on their property. The Alberta Liquor Board issued a suspension on their liquor license until the owners addressed problems on the property. The police arrested the corrupt bar manager. The owners hired an entire new staff and banned the drug dealers from the premises.

Once these changes were made, crime at the Klondiker plummeted. The Klondiker also experienced a 30% increase in their sales because the changes attracted more customers. And nearby businesses reported fewer crimes, such as shoplifted goods, which were being stolen to purchase drugs at the Klondiker.

In a similar example, the city of Chula Vista, California, was experiencing problems at some of its 27 motels. Problems ranged from drug dealing, prostitution, parolee violations, thefts from rooms, and disputes over payment. Crime analysts found that only five motels generated more than half of all calls for police service at motels. Wanting to solve the problem, the city council decided to roll out a three-stage crime prevention strategy. In stage one, police visited the motels and educated the managers on crime prevention improvements they could make specific to their properties. In stage two, the city sent code enforcement officers to inspect whether the motels complied with the police’s requests in stage one. In stage three, the city enacted a permit-to-operate ordinance; if motels exceeded the acceptable number of calls for service to police, they were required to enter into a memorandum of understanding with the city to take appropriate corrective action.

The three-stage process was successful. The five top-tier properties generating the most calls experienced a 68% reduction in calls for police service. Mid-tier properties experienced an additional 36% reduction.

These motel examples illustrate two important facts about crime. First, residents can seldom solve these crime problems. Resident-driven approaches, such as community-oriented policing and neighborhood watch, sound good in theory but research suggests they have little ability to reduce crime. This is because residents almost never have control over the places experiencing crime, even if they live there. Second, to reduce crime, you need to get the owners of crime-ridden properties to change the way they operate their properties. This can either be physical changes to the building (e.g., fixing broken windows) or changes to how people use the property (e.g., employee training or setting rules for place users). In short, police and residents cannot fix broken windows, but property owners can.

But how did these cities know to incorporate property owners into their crime reduction strategies? There are two reasons. First, they understood the necessary elements of a crime. Second, they understood that one element—place managers—is the most important in reducing crime. In this article, we explain the power of place managers and how they can help you solve your city’s crime problems.

Why Do Such a Tiny Fraction of Places Have a Lot of Crime?

People tend to make two mistakes when thinking about crime. The first is that they focus on the people who commit the crimes. This often leads to the public demanding that the police make more arrests, usually leading to little change in a city’s crime rate. The second is that they focus on victims. The media tends to focus on those who are harmed by the crimes to spark public outcries, which usually lead to demands for increased arrests or community policing, which again, seldom reduce crime. While offenders and victims are important, they only make up part of the story. People often overlook the places where crime occurs.

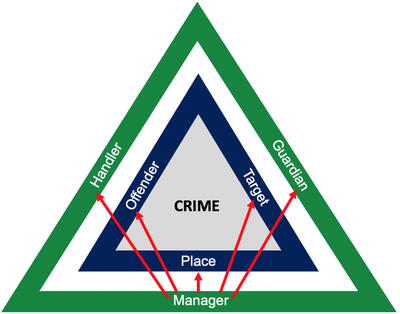

In 2005, Ronald Clarke and John Eck created a tool for police to understand why crime occurs: the problem analysis triangle (Figure 1).

The inner triangle, colored in blue, depicts the necessary conditions for a crime to occur. You need a motivated offender to converge with a target at a place. A motivated offender is anyone sufficiently willing to commit a crime. A target can be a person or object—such as a car, smartphone, or jewelry—that is enticing to an offender. A place refers to a property parcel. When these elements converge, it creates a crime opportunity. If you remove one of the elements, crime cannot occur. This is like what we learned in kindergarten about fire: if you remove heat, fuel, or oxygen, there is no fire.

The outer triangle, colored in green, depicts controllers. These are the people or organizations who influence or control the inner elements. Guardians, such as bystanders or security guards, protect targets by guarding or watching out for them. Handlers, such as parents, spouses, or coaches, have an emotional connection to offenders. Managers are the owners and operators of places.

If a single controller is present, even when the inner three elements converge, crime is unlikely to occur. Controllers have sufficient power to prevent crime. For example, if a motivated offender encounters an unlocked car in a parking lot, but there is an attendant roaming around the lot guarding the vehicles, crime is unlikely. Although, a single crime might occur if all controllers are momentarily inattentive.

A place becomes a hotspot for crime when it has repeated convergence of the inner elements and consistent inattentiveness by controllers; this creates crime opportunities. As we explained in our second article of this series, while crime hotspots are rare, they generate most of a city’s crime. You could put “cops on dots” (hotspots policing), but the cops will have to keep returning to the dots every shift. Once police leave the hotspot, crime creeps back. And as it turns out, there is a way you can make crime problems disappear for good; you need to solve problems using place managers.

The Power of Place Management

Place managers are the most powerful actor in the crime triangle for two reasons. First, they can implement crime prevention changes on their properties because they have legal authority over their places (derived from property rights). Ownership instills a right to:

• Organize space, such as the layout of a building or making repairs (e.g., the right to renovate).

• Regulate the behavior of people who use their property (e.g., no shoes, no shirt, no service).

• Control access to their property (e.g., trespassing laws and business hours).

• Acquire resources (e.g., buy property to build equity).

These rights apply equally to owners of big-box stores, apartment buildings, single-family homes, as well as parks and public squares (i.e., the city government). Non-owners cannot make changes to property (e.g., renters cannot renovate their apartment units without the landlord’s consent).

Second, because of these property rights, place managers can influence all other components of the crime triangle. If the place manager of a big-box store decides to stock items that are at a high risk of theft, he is increasing the number of targets at his place. But he can simultaneously add guardians, such as hiring loss prevention or security officers, to mitigate this risk. Similarly, to reduce shoplifting, the owner of a convenience store can limit the number of teenagers who can enter the store at the same time (reducing offenders). A shopping mall owner can implement a policy where teenagers must be accompanied by an adult at the mall on Friday and Saturday evenings (adding handlers).

But the reverse is not true. Guardians, such as security guards, do not decide which products (potential targets) are sold in the store. And the adults (handlers) and teenaged shoppers (potential offenders) do not get to dictate a store’s or mall’s business hours, arrangements of shelving, or stocking of merchandise. Place managers are the only actor in the crime triangle who can dismantle crime opportunities by influencing all sides of the problem analysis triangle (more on this in our fifth article).

What Role Can Residents Play?

While place managers are your key actors for crime control, residents can still serve an important role in the process. A problem-solving effort in Kansas City, Missouri, illustrates this.

For years, police officers were receiving an average of 55 calls for service per month from residents about a single dilapidated apartment building called the Creston. Its crime problems ranged from drug dealing, thefts, and prostitution to assaults, robberies, and homicides. Officers spent hundreds of hours monitoring activity on the property trying to arrest people involved in the crimes. Violence escalated to the point that to ensure officer safety the police department had to deploy four officers every time they responded to a call at the property.

Having no success using traditional policing strategies, three officers decided to solve the problem. First, officers gave all nearby residents business cards with a number they could call anytime to report illegal activity. Second, officers conducted surveillance of the property to gather intelligence. Third, officers identified the owners of the building and tried to get them to address issues on their property. The owners refused.

Upon further investigation, the officers discovered that there was a Housing and Urban Development (HUD) lien on the building, making HUD just as responsible for the building as the owners. So, in the fourth stage, the officers began working with HUD, the fire department, and health inspector. They deemed the building uninhabitable. So, HUD took action to improve living conditions for tenants until they could find them new places to live. HUD also paid to improve security: they hired 24-hour security guards, a doorman who checked everyone’s photo identification upon entry, and installed a metal detector at the entrance. HUD also evicted drug dealers arrested by police. These changes were followed by a 60% drop in calls for police service. Because the building was uninhabitable, HUD tore it down.

The Creston apartment building example teaches three lessons about residents. First, residents can bring problems to the police and city’s attention, raising them at public meetings or by calling the police. Second, residents can provide valuable information. Residents helped police build a case for HUD action. Third, residents are often unable to carry out solutions. Only the place manager—in this case, HUD—had the authority to improve security and living conditions in the apartment, relocate residents to more livable housing, evict drug dealers, and demolish the building.

Conclusion

We titled our article with the question, do residents matter the most in reducing crime? Our answer is no.

When a noteworthy crime happens, residents demand action. And usually, cities respond with two ineffective solutions: engaging residents and arresting more people. In this article, we showed you why these strategies have limited effectiveness. Your police department and residents have no control over broken windows, literal or figurative.

Instead, ask yourself, who are the place managers? Or better yet, ask who owns the building with the broken window? And why haven’t they fixed it? By acting upon this question, you will identify the people who can dismantle crime opportunities (the subject of our fifth article). Place managers can also resolve other local government problems, such as reducing blight, preventing attractive nuisances, stopping illegal dumping, and eliminating pollution or sanitation problems.

While police can facilitate problem-solving, their ability to dismantle crime opportunities is limited. And as we will show in next month’s article, this is also why having officers arrest more people is an ineffective crime reduction tactic. We will explain how you can reduce crime in your city while simultaneously reducing the number of arrests your officers make.

SHANNON J. LINNING, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada. She researches place-based crime prevention and problem-oriented policing.

TOM CARROLL, ICMA-CM, is city manager of Lexington, Virginia, USA, and a former ICMA research fellow.

DANIEL GERARD is a retired 32-year veteran (police captain) of the Cincinnati Police Department, USA. He currently works as a consultant for police agencies across North America.

JOHN E. ECK, PhD, is an emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Cincinnati, USA. For more than 45 years, he has studied police effectiveness and how to prevent crime at high-crime places.

Other articles in the series:

Part 1: Do Solutions to Crime Need to Be Complicated?

Part 2: Is Crime Widespread?

Part 4: Do More Arrests Reduce Crime?

Part 5: Can the Police Solve All Crime Problems?

Part 6: How Can You SCRAP Crime Proposals that Are Likely to Fail?

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!