This is the second in a three-article series about high-crime places. Access the first article here and the third article here.

Problem Properties and Hot-Dot Radiation

In last month’s article, we showed how the police can be handcuffed by high-crime properties and how super controllers hold the key to making a difference. Some of these properties cause problems beyond their boundaries. Driving down crime at these high-crime properties will improve overall neighborhood safety. Consider the following example.

Residents of the Franklin neighborhood in Provo, Utah, repeatedly called the police about issues such as illicit drug distribution, drug use, overdoses, assaults, trespassing, sexual offenses, thefts, and impaired driving. When residents called for help, the police responded and arrested people involved in illegal activities. But this arrest-focused police response had little effect on neighborhood crime rates; new offenders would come along and repeat the same behavior, or arrested offenders would return to the same activities after their release. So, rightfully frustrated, residents kept calling.

Tired of responding endlessly to the same calls involving the same people, the Provo police decided to try a problem-oriented approach. They analyzed patterns in the calls for police service. Many of the neighborhood’s calls could be traced back to a single address. The police realized that one four-unit dilapidated apartment building had been generating an average of 135 calls for service a year for over a decade.

To put that number into context, the Provo Police respond to an average of 150,000 calls for service annually. At the time, Provo had 33,000 households. If each Provo household generated the same number of annual calls for police service (135) as this one problem apartment building, the 114 officers of the Provo police would have received nearly 4.5 million citizen calls for service yearly. The apartment building was an example of the law of crime concentration; a few cause the most.

The police probed further; they learned that the property had developed a reputation as a haven for people experiencing homelessness, mental health issues, and substance abuse. The three tenants, all behavioral health patients, were repeatedly victimized. Collectively, the tenants called the police 184 times in five years. One tenant, besides being regularly victimized, was also suspected of committing six crimes.

Data analysis also linked 911 calls at other properties in the neighborhood to the apartment building. Nearby residents reported that “crimes being committed at this address were bleeding onto their property diminishing property values and scaring away potential customers at surrounding businesses.” Crime was radiating from the problem apartment building to other properties; it was facilitating illegal activity nearby—such as burglary and theft—to fund the offenders’ substance use.

Crime researchers call places like the Provo apartment hot-dot radiators. They are high-crime places (i.e., properties) that increase crime at neighboring places. A key feature of hot-dot radiators is that there is no deliberate attempt to encourage crime at nearby places; crime nearby is merely an unfortunate byproduct of bad place management decisions at the radiator. Since radiators—like the Provo apartment—drive crime in the area, arresting offenders who target nearby properties won’t solve the problem. If you do not address problems at the radiator, it will remain a neighborhood crime attractor, used by either the same or new offenders.

Despite resident calls coming from properties all over the Franklin neighborhood, the data showed that this was a place problem, not a neighborhood problem. So, the police decided to adopt a place-based strategy. Provo police contacted the property owner with hopes of creating a partnership. The owner wanted to demolish the building and build a larger complex but could not due to zoning restrictions. So, the owner took no interest in the property, other than collecting subsidized monthly rent checks. Fortunately, the lack of cooperation did not deter the police. They decided to continue their place-based approach, but this time with the help of some super controllers.

When Property Owners Aren’t Cooperative

As we noted last month, crime-ridden properties often have many other problems not related to crime. Unsurprisingly, the police documented poor conditions at the Provo apartment building, including mold growth, insect and vermin infestation, sewage backups, non-functional heating systems, a lack of smoke detectors, and building code violations involving the electrical system. The numerous infrastructure problems created many safety hazards for the building’s tenants. Enforcement of these health and safety violations was outside of the police department’s authority; the violations were the responsibility of other city agencies.

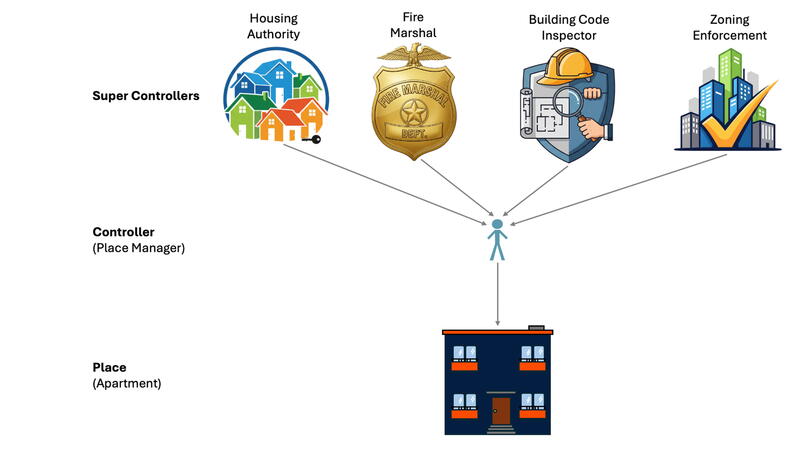

The Provo police assembled a team of super controllers to compel the owner to change the conditions at the apartment. Super controllers, acting in their formal capacity, have some type of legally enforceable relationship with the property owner and can mandate change or invoke sanctions for non-compliance, including shutting down a problem property.

The police identified four super controllers:

1. The housing authority, who applied pressure to the county’s behavioral health agency as their mental health clients resided in the building and the agency assisted with subsidizing the residents’ monthly rental payments.

2. The fire marshal, who discovered numerous fire code violations and issued violation orders.

3. The city building inspector, who issued several emergency repair orders to the building owner.

4. A civilian zoning enforcement division of the city, who uncovered a city licensing requirement that permitted building safety/health inspections, which facilitated the joint inspections and violation orders.

The housing authority convinced the behavioral health agency to move their clients out of the problem apartment building, which ended the guaranteed monthly rental income for the owner. The zoning officer, building inspector, and fire marshal jointly issued emergency work orders and notices of violations to the property owner. The owner was put on notice that if they did not correct the violations, the building would be condemned. They also warned that their team would be making regular monthly inspections of the property to monitor compliance.

The property owner promised to fix the property, but weeks went by with no action. The joint team of super controllers continued their inspections, issued more notices of violations/non-compliance and eventually the owner chose to sell the property. Provo police and the other city regulatory agencies involved in the project met with the new owner and outlined the building’s problems. The new owner renovated the building and began renting the units to new tenants.

Using a team of super controllers to change conditions at a long-term problem property worked. Calls to the Provo police about the building stopped. And calls to police from properties around the building immediately dropped nearly 50%. A year later, calls to Provo police had dropped 92%.

Other Crime Radiation Types to Consider

When dealing with a problem property, in addition to hot-dot radiators, city/county managers and police officials need to be aware of two other types of crime radiators that may occur: veiled-dot radiators and cold-dot radiators.

Veiled-dot radiators are places that, with the encouragement of place owners/managers, serve as hosts for consensual crimes. The scrapyard in last month’s article is a prime example. The scrapyard owner regularly purchased stolen metals thereby encouraging thieves to victimize nearby properties. There are many other examples. A few owners of auto wreckers will encourage catalytic converter theft throughout a city. A few convenience store owners will encourage shoplifting at nearby properties to stock their shelves. Because these crimes are consensual, the people involved are unlikely to report criminal activity. So, veiled-dot radiators will likely appear as low-crime or crime-free properties in police report data. They will not attract attention, unless police actively look for them. And until police connect the crimes to the radiator and address problems at the radiator, the police will continue playing a game of whack-a-mole traveling perpetually from call to call.

Cold-dot radiators are low- or no-crime places that unintentionally create or increase crime at nearby places. Some transit stations, for example, can be cold-dot radiators. Offenders know that vehicles parked nearby are often unattended for an extended period, so they have time to break into them. Unlike hot- or veiled-dot radiators, cold-dot radiators do not intentionally attract offenders for criminal purposes. Instead, offenders encounter them while going about their daily activities and take advantage of the opportunities for crime. Cold-dot radiators are difficult to identify from aggregate police data. Often, experienced patrol officers and investigators can identify them.

The bad news about crime radiation is that what happens at places doesn’t always stay at places; they spread crime. But the good news is that if you address problems at crime radiators, you usually spread benefits. Crime researchers call this a diffusion of benefits. Not only will crime decline at the place, but crime will also decline across the neighborhood.

Conclusion

The Provo apartment example teaches us three lessons. First, sometimes what appears to be a neighborhood crime problem is actually a place problem. It only takes a single, poorly managed property to generate a lot of crime in an area. Police need to gather intelligence and analyze data to determine if they are dealing with a crime radiator. And if a place is radiating crime, then suppressing crime at that place can create a diffusion of benefits; once the new owner addressed the problems at the Provo apartment, not only did crime on the property decline, but crime at nearby properties declined, too. In short, it’s more efficient and effective to treat places than to treat neighborhoods.

Second, crime radiation is not always obvious. This is particularly important when dealing with veiled- and cold-dot radiators that appear crime-free in police report data. Neighborhood residents may be calling about crime on their properties and will expect the police to take action on their respective properties. Residents may not know that another property is driving the problems they are experiencing. The police need to identify the connection between residents’ calls and the crime radiator.

Third, crime radiation is often best addressed by the place managers of crime radiators. If crime problems are caused by a place, then police repeatedly arresting offenders is unlikely to solve the problem. Instead, you need to adopt a place-based strategy to change conditions at the radiator. But when place managers are uncooperative, you can get super controllers involved. Crime-ridden properties often experience other non-crime problems. So, marshaling agencies who can pursue health and safety concerns, building code violations, unpaid tax liens, occupancy limits, and the like tend to also cut crime at and around these places.

What if you had a lot of the same types of places—motels or convenience stores, for example—that are experiencing problems? Next month, we look at regulatory approaches to address problem properties.

SHANNON J. LINNING, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada.

TOM CARROLL, ICMA-CM, is city manager of Lexington, Virginia, USA.

DANIEL W. GERARD is a retired 32-year veteran (police captain) of the Cincinnati Police Department, USA.

JOHN E. ECK, PhD, is an emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, and a lecturer at the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey, USA.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!