Companion animals are an important part of American life, with about 67% of U.S. households owning pets, over 60 million owning at least one dog, and over 40 million owning at least one cat.

Responsible pet ownership and caring for one’s pet as a family member is now common throughout the country, although regional and cultural differences exist. With the recognition that pets, for many, are surrogate family members, or simply accepted as part of the human family, they are treated just like other human family members in many ways. While in some situations this is a welcome development, in other cases, especially in households where there is domestic violence, or child/elder abuse/neglect, this can pose serious problems not only for the human family members, but also for the animals that are part of the family.

Several International City/County Management Association (ICMA) blog posts and publications have addressed strategies for managing animal services in communities. Most have discussed issues related to running the local animal shelter, solving problems associated with community cats, and finding ways to decrease the numbers of animals euthanized, while also increasing the number of animals who are returned to their owners when lost. The role of the animal control officer has been redefined in recent years, and increasingly communities are developing “innovative programs that keep people and pets safe, happy and healthy.”1,2,3

However, these articles have not really addressed an important issue, related to where, within the city or county’s organizational structure, the role of the animal control officer (ACO) resides, and how ACOs relate to and interact with law enforcement.

This article addresses that issue in the context of some recently released data from the FBI on animal cruelty crime across the country. The importance of understanding the link between animal cruelty and public safety is discussed briefly below, followed by some preliminary analyses of the data. This article will discuss the advantages of having animal services agencies and law enforcement working more closely together in communities, in order to facilitate the best mechanism for ensuring that incidents of animal cruelty are properly reported to the FBI along with other crimes against society, property, and people, as is typically done by law enforcement officers for other crime.

Background

Domestic and interpersonal violence (IPV) committed against family members is common in society and is a large public health concern.4 It is also well known that child abuse and neglect often co-occur in households where animals are abused or neglected.5 Research has shown that those who have committed both IPV and animal cruelty are also more likely to have been involved in other violent crimes such as property crimes, drug offenses, and assaults.6

On January 1, 2016 the FBI began collecting information about crimes of animal cruelty from law enforcement agencies that participate in the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). The decision to specifically track crimes involving animals, instead of just grouping them into an “all other offenses” category, was made, in part, to be able to examine, with actual data, the concurrent nature of animal cruelty and other forms of violence.

2018 NIBRS Animal Cruelty Data

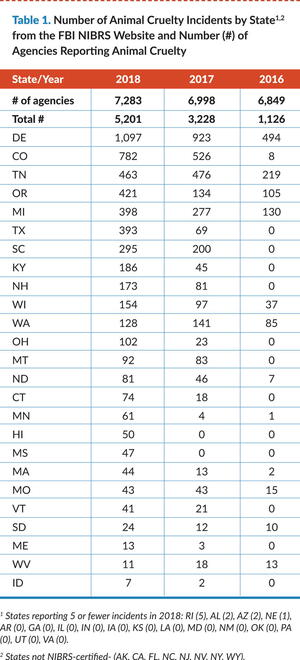

Table 1 shows the number of animal cruelty incidents reported in 2018, 2017, and 2016 from the NIBRS FBI websites. Although not broken out here, animal cruelty is classified by the FBI in one of four categories, including simple/gross neglect, intentional abuse and torture, organized abuse/animal fighting, and animal sexual abuse. In 2018, the majority (68%) of animal cruelty incidents involved neglect, and a lesser but still significant fraction of incidents involved intentional abuse and torture (29%). The remaining 3% of incidents were categorized as either organized abuse/animal fighting, sexual abuse, or some combination of the other types of abuse.

In 2018, there were 5,201 animal cruelty incidents reported from 29 states. This was an increase of about 61% from the numbers reported in 2017 (3,228) and an increase of over 460% from the 2016 total of 1,126. It is likely that the increase in numbers of animal cruelty incidents does not mean that more animal cruelty actually occurred in 2018 and 2017 over previous years, but instead that more jurisdictions were reporting, and also that more incidents were being reported from the communities submitting data. In 2018, only 7,283 (46%) of all (16,609) law enforcement agencies in the country were reporting data in NIBRS.

There are many reasons why a state’s animal cruelty crimes would not be reported in the NIBRS system. Some of these are alluded to in the footnotes to Table 1. For example, not all states are currently certified to report in NIBRS or they may be one of a handful of states that still use a different system for reporting their crime data to the FBI. Beginning in January 2021, however, NIBRS will be the only system that will be available to law enforcement agencies for crime reporting.7 In addition, although a state may be certified to report their crime data in NIBRS, the state’s Records Management System (RMS) for reporting crime may not be up-to-date to include the necessary data elements for animal cruelty. Finally, officers may not yet be trained on how to record the data for those new data elements and if ACOs are not within a law enforcement agency, there could be a disconnect between the crime data compiled by the law enforcement agencies in a community, and those working in animal services responsible for animal control and humane law enforcement.

Because only law enforcement agencies with an originating agency identifier (ORI) number are able to submit data in NIBRS, if animal cruelty incidents are being handled by a humane society, public health department, or other general services organization within the community, it is possible that crimes involving animal cruelty may go unreported to the FBI. In addition, the animal cruelty crimes may not be linked to other crimes that may have occurred at the same time as the animal cruelty if only an animal control officer responded to the incident, or if the agencies do not work together on data collection and reporting. One way to do this is by creating a memorandum of understanding (MOU) or other agreement for sharing of information between law enforcement agencies and animal control organizations.

A survey done in 2012 by Randour and Addington found that only about half of all animal control officers across the country work in law enforcement agencies.8 Therefore, unless an animal control agency has an existing working relationship with a law enforcement agency in their community, it is unlikely that the data that they collect will make it into the NIBRS database. Since NIBRS is an incident-based reporting system, it is important that all data associated with a single incident is captured together in the database. Therefore, there must be a holistic and well-integrated submission of data to the FBI that includes not only the crimes involving animal cruelty, but also the other crimes that law enforcement would typically be responsible for tracking.

Importance of Other Concurrent Crimes

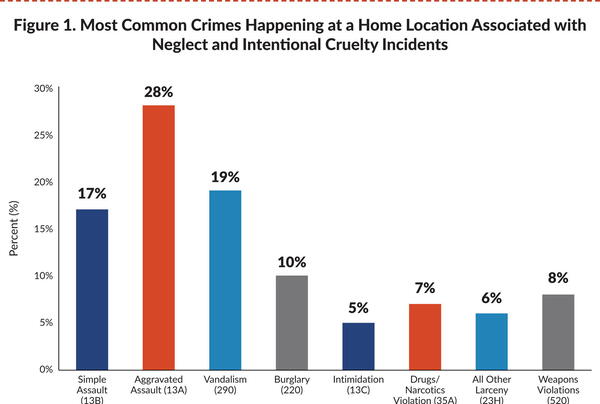

What other crimes typically occur in association with animal cruelty and how might this be used to help law enforcement agencies, animal management services, and humane law enforcement officers work together to try and reduce crime and increase public safety in the community? Figure 1 is a bar chart showing the most common offenses that were found to occur concurrently with animal cruelty, based on an analysis of the 2018 NIBRS animal cruelty data. Only crimes involving neglect and intentional cruelty were included in this analysis but recall that those two types of animal cruelty make up 97% of the data from 2018. The crimes most frequently found to occur in association with animal cruelty were assaults, vandalism, burglary, and other crimes against society, such as drugs/narcotics offenses and weapons law violations. The figure illustrates the importance of how paying attention to crimes involving animal cruelty could help communities anticipate when and where other types of crimes might occur.

Location of Animal Cruelty Crimes

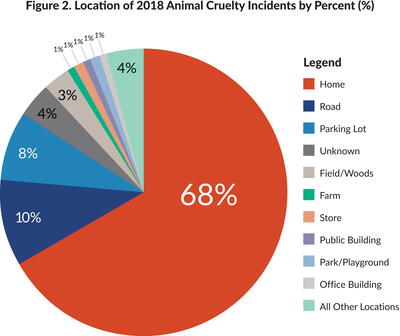

Recalling the discussion at the beginning of this paper about the importance of the link between animal cruelty and family violence, and the finding that child abuse and neglect often occur in households where animals are also abused or neglected, it is important to look at the data to see what we know about where animal cruelty crimes occur most frequently. Figure 2 shows this data in a pie chart and illustrates that the majority (68%) of animal cruelty crimes do, in fact, occur at a home or residential setting. Therefore, it is especially important to the health and welfare of all human family members to pay attention to reports of animal cruelty in the community. When one recognizes that these reports could be the tip of the iceberg for what else might be going on at that home, one realizes why calls to animal control about an abused dog or cat could help law enforcement identify situations where other crimes either have occurred or are likely to occur in the future.

Conclusion

The importance of collecting crime data involving animal cruelty has been illustrated in this article by sharing some of the 2018 NIBRS data from the FBI. The data illustrate how animal cruelty is related to other crimes and why this is important for improving public safety in the community. The recognition that other crimes often occur concurrently with animal cruelty provides an opportunity for both animal control and law enforcement agencies to work together to share information and collaborate for the benefit of the entire community.

In the blogpost mentioned at the beginning of this article about the ways in which the role of ACO has been redefined in recent years, the notion of a “community-minded field services liaison” was discussed. This new brand of ACO works on a personal level within the community doing community outreach and education, almost like a family pet social worker. This is an important model that all communities should consider. Given the link between animal cruelty and domestic and family violence, it would make sense if animal control officers teamed up with police and other law enforcement officers, to work together in the community to solve the problems that are encountered every day in cities and counties around the country. It would also help to improve the animal cruelty data collected by the FBI that is important for developing a better understanding of crimes involving animal cruelty.

Endnotes

1 https://icma.org/documents/win-win-strategies-communities-managing-animal-services

2 https://icma.org/blog-posts/how-get-innovative-animal-control

3 https://icma.org/blog-posts/redefining-role-dog-catcher

4 https://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/toolstemplates/entertainmented/tips/Violence.html

6 Hoffer, T., Hargreaves-Cormany, H., Muirhead, Y., and Meloy, J.R. Violence in Animal Cruelty Offenders. New York: Springer International Publishing, 2018.

7 https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ucr/nibrs

8 Randour, M.L. & Addington, L.A. (2012). “Summary of Survey to Animal Control Agencies on Animal Cruelty Crime Statistics,” Washington, D.C.: Animal Welfare Institute.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!