Organizations, whether in the public or private sector, must brand themselves as employers of choice, in order to attract and retain the right talent. The brand communicates the values of the organization, its culture, and how it values and treats its people. Decisions about what type of brand the organization wishes to create are typically made by the board/council, working with executive management, due to the importance of how positively talent views the organization as an employer in determining its success. The brand is also a signal to all parties of interest as to what the organization offers and how it intends to meet its objectives and purpose.

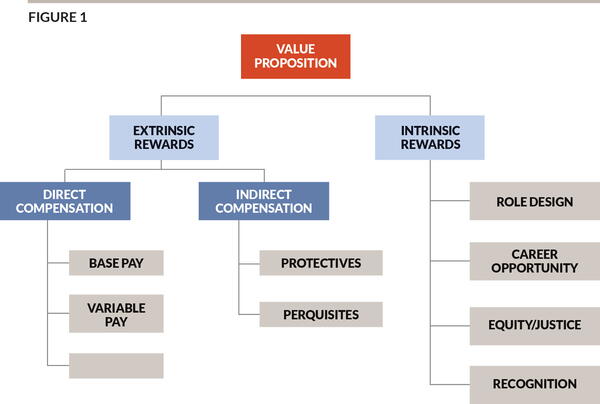

A significant component of the brand is the value proposition that is offered to talent. It consists of all the conditions of employment and what the organization offers in return for the contributions of workforce members. Figure 1 illustrates the components of a value proposition.

The components of the value proposition offered by organizations vary. Some employers will stress non-monetary items, such as career opportunities, an attractive culture, meaningful and challenging work, recognition, and fair treatment. Economics may preclude competing with other organizations on compensation and benefits alone. Public sector organizations and nonprofits with a charitable mission are more likely to attract those who value making a difference or serving a cause. Private sector organizations tend to stress monetary rewards more. Relying on money sometimes does not work well. (Henry Ford had to pay much more than others to get people to endure the assembly line—and still had turnover of 200 percent or more.) Public sector organizations may also face stricter limitations on the type of compensation used (e.g., stock programs) and may also face greater scrutiny on very high pay levels.

The extrinsic reward components consist of fixed costs and variable costs. Base pay and the cost of benefits generally increase each year. Health care costs continue to rise much faster than inflation and unless organizations reduce benefit levels or increase the percentage of costs paid by employees, the employer costs increase. Salaries and wages can be reduced in cases where contractual agreements do not prohibit it, but this can have a detrimental impact on employee satisfaction. People assume they can adjust their standard of living to fit their income stream and unilateral reductions in that stream can be viewed as a breach of contract (social if not legal).

The federal government and many state and local entities use automatic, time-based step increase programs to administer base pay. When revenues drop, as they did at the onset of the pandemic, costs can become misaligned with resources. During the 2007-2010 financial crisis, the GS step structure was frozen, but employees continued to receive step increases. Using automatic step progression removed options for controlling costs. Without reductions in current rates the only way for employers to adjust workforce costs downward to align them with revenues is to reduce headcount, which may mandate terminating people who will be needed when conditions improve.

Organizations must manage compensation in a manner that is sound from an economic and business perspective. One of the most common oversights is failing to be clear about the impact of the economy on pay budgets and pay adjustments. Employees often think high inflation rates should be offset with commensurate increases to sustain the purchasing power of their income. However, sustaining purchasing power is not the responsibility of employers. Economic metrics like inflation, cost of living, and unemployment rates do tend to have an impact on labor market conditions and competitive pay rates, and employers must consider the end result of economic conditions. But if inflation does not result in increased market pay levels, the organization must focus on remaining competitive and not assume responsibility for maintaining employer real income levels.

Employers must respond to the cost of labor and not the cost of living. Macro-economic conditions cannot be controlled by organizations. If the competitive cost of labor changes for specific occupations, the employer must consider how to respond in order to remain competitive for talent. The cost of labor is more strongly influenced by the relationship of supply to demand for specific skill sets than it is by inflation or unemployment levels. For example, competitive market rates for IT specialists may be increasing rapidly, even during periods of low inflation, caused by a shortage of people who are competent to work with the latest technology. Even during periods of high inflation, market rates for skill sets not in demand may be static.

What Purpose Does a Compensation Philosophy Serve?

A compensation philosophy establishes agreed upon principles that will guide how compensation is administered. If the organization commits to paying for performance, however defined, that principle will guide program design and administration. The philosophy can also establish a commitment to values, such as pay equity. Sound compensation management ensures people are rewarded based on:

1. The value of the role they play (both to the organization and in the labor market).

2. The person’s competence in the role.

3. The contributions made that help the organization meet its objectives.

What a person looks like, what they believe, where they came from, and any other personal characteristics not related to the value they provide should not impact how much or in what manner they are rewarded. A commitment to equitable pay enables an organization to develop analytical processes to monitor pay relationships and ensure they reflect equitable treatment.

Merely putting a philosophy statement on paper does little; the principles it defines must be adhered to. If employees and other parties do not agree with the philosophy, management must decide how to address their views. If actual practice is not consistent with the stated principles, management must evaluate how programs are designed and administered and determine if changes to the philosophy or the practices are needed. If an organization does not ensure that employees know clearly what is expected of them and how they are performing on a continuous basis, it will make convincing them that they are being treated fairly and appropriately more difficult.

Longevity

Research supports the principle that paying for performance increases the motivation to perform well. Research also shows that performance must be defined in a manner that fits the situation. For example, using longevity as one of the determinants of pay may be justified if experience in a role is highly correlated with the ability of an incumbent to perform well. Field crew members in a water utility will typically become more familiar with the system, increasing the knowledge and skill they use to maintain the system. When knowledge and skills are organization-specific, they can only be acquired by being on the job. When consulting with a water utility we realized that having a system that was several hundred years old had resulted in a myriad of hookup methods that were not reflected in the engineering plans, making experience with that system valuable. Conversely, newer incumbents in technical fields can have more up-to-date knowledge, making longevity less relevant. The relative value of education and experience will vary based on how specific the knowledge is to the organization and how important it is to utilize conceptual principles to deal with unique situations. An automatic link between longevity and pay rates makes no provision for reflecting unsatisfactory performance in someone’s compensation, leaving termination as the sole consequence available.

Performance

Other principles must be included in the compensation philosophy. It should also address the methods and processes that will be used to manage performance and administer pay. Adopting a strategy that results in paying people in a manner that reflects the relative internal value of the roles they play can result in using a formal job evaluation system to ensure the relative internal values that determine the grade and pay range assigned each job.

Geographic Market Rates

Alternatively, adopting a strategy that results in paying people in a manner that is externally competitive alters the primary basis for establishing pay ranges. A policy that emphasizes the establishment of externally competitive pay ranges must define how the organization defines its competition for talent. A city with a population of 50,000 may decide to compare to cities of a similar size that are within a specific geographic area. But it may also choose to compare to the state government and counties. Further, it may decide to compare to private sector organizations for occupations that have cross-sector mobility. Finally, it must decide on a posture relative to prevailing market rates—above, below, or at market average. It is also possible to pay at different levels relative to competition. Critical occupations may be paid above market levels while others are paid at market levels.

Remote Work

One of the conditions of employment that has recently seen dramatic change is the location of work. Historically employees have lived close enough to a central location to enable commuting. But when the pandemic began, a large percentage of workers were driven to remote work locations. Surveys indicate that a significant number of employees do not see the need to return to the office and do not want to do so. Some will want to vary their location day to day, based on the need for face-to-face interaction with colleagues or the public to be effective. This makes permanent remote work a viable alternative. But new issues are created if people relocate to distant places. There has been an outflow of professionals from the San Francisco Bay Area to Northern Nevada and other lower cost locations, bringing into question whether it is still necessary to pay the same rates for someone working elsewhere.

An employer that is willing to let employees make decisions about where they do their work may be viewed more positively than one mandating that everyone must work in a central location. But the impact of work location on productivity and on the effectiveness of peers and customers must also be considered. An employee who processes permit applications submitted by contractors may feel they have to do their work face to face, while an IT or accounting specialist can be just as effective from any location.

What Issues Does a Philosophy Need to Address?

The board/council and executive management need to agree on the compensation philosophy:

- What forms of compensation will be used?

- How will the value of each role be determined (internal equity, external competitiveness)?

- How will performance be defined, measured, and rewarded?

- What process will be used to administer compensation? Who is involved? Who decides?

- How does the organization define its competition for talent?

- What will the organization’s competitive posture be?

- How will the compensation philosophy be communicated and to whom?

- When, how, and by whom is the philosophy evaluated to ensure its continued relevance?

When consulting with organizations, the first step we take is to ascertain the views of important stakeholders and to seek agreement on the principles. Without a clear understanding of how a compensation philosophy will impact the effectiveness and acceptance of strategies and programs, it is possible to develop recommendations that ultimately will not be used by decision-makers. Philosophy is not a theoretical exercise; it serves as the navigational system to guide the organization to its desired destination.

The Value of a Clearly Articulated Philosophy

Without a clear compensation philosophy, decisions tend to be made independently case by case. This can result in inconsistent administration across departments, occupations, and time. And even though a compensation philosophy is a good fit to the context within which it was developed, environmental change may necessitate re-evaluating the principles that are being applied. The pandemic has administered an unanticipated shock and being able to call upon a well formulated and clearly articulated compensation philosophy can facilitate sound decisions about how to react to the altered context. Continuous evaluation of the compensation philosophy to ensure it meets current conditions has become mandatory.

Taking the views of all parties-at-interest into consideration when a philosophy is developed and when alterations are being considered can increase the level of acceptance. Although management may be unwilling to hold a democratic election, it is important to create an open channel of communication that can gather opinions and enable decisions to be explained once they are made. Dialogue on a continuous basis can engage employees and assure them that their views have been heard and considered.

A well-articulated compensation philosophy establishes the guiding principles that underlie compensation management. The methods and processes that are used may vary across the organization due to local contextual differences, but should be consistent with those principles. The philosophy statement communicates a good deal about an organization’s values, its culture, and its views related to how it values its people and informs all parties-at-interest as to the principles that guide compensation administration. It is an important part of both the employer brand and the value proposition.

ROBERT J. GREENE, PhD, is a consulting principal at Pontifex (rewardsystems@sbcglobal.net).

PETER P. RONZA is president of Pontifex (pronz@pontifex-hr.com).

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!