Local governments’ uptake in strategy has been growing. You rarely see a municipality that doesn’t have a strategic plan or any sort of strategy. It is important work as it leads to better community engagement, employee engagement, and prioritization.1 But nothing is perfect. Are you aware of its limitations? Does it build the foundation you need to serve the community and to manage your organization? To better answer those questions, let’s take a step back and understand the approach that activates this work.

The Evolution of the Approach

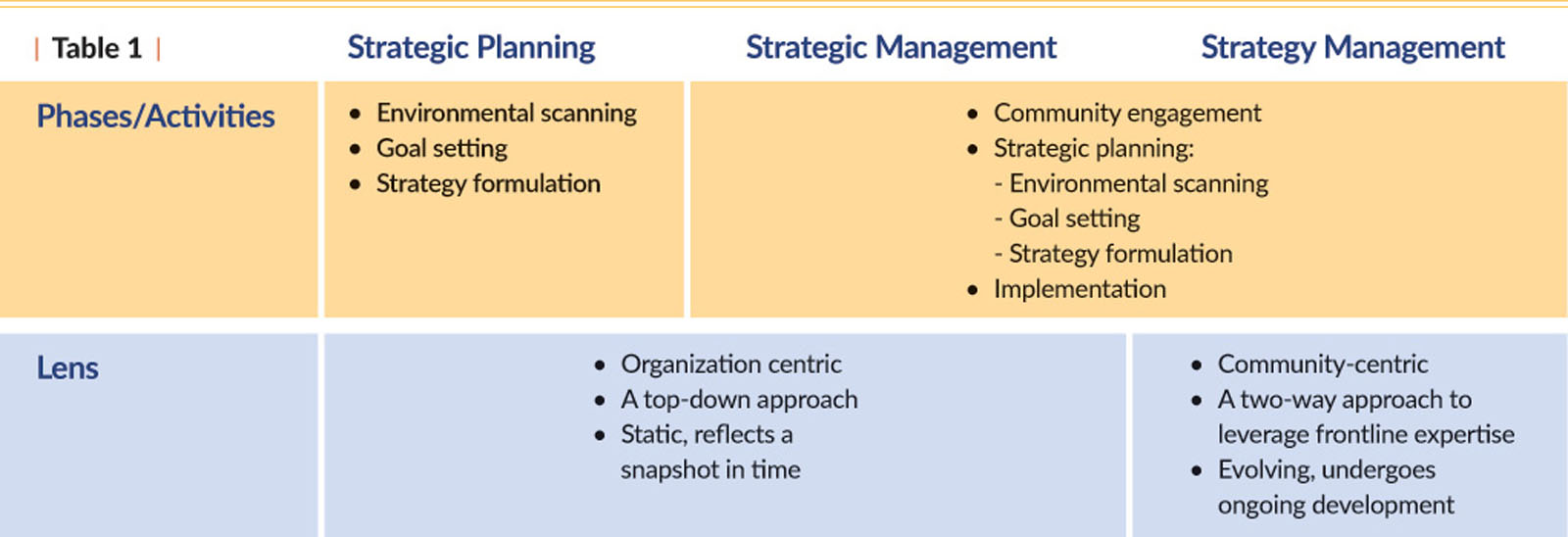

The work to develop a strategic plan or any sort of strategy is guided by a discipline called strategic planning. The approach was introduced to the public sector in the early 1980s as an innovation from the best-run private sector companies. It includes a series of phases or activities: scanning the environment, setting the vision and goals, and formulating the strategy. Strategic planning allows managers to think systematically about the future of the organization and the environment in which it operates by blending futuristic thinking, objective analysis, and subjective evaluation of values, goals, and priorities to chart future direction and courses of action.2 But the value of good strategic planning is more than just inspiring strategic thinking. Many feel the need to use strategy to drive decisions and actions and to manage changes more effectively.3

To further enhance the organization’s ability to advance the goals and implement the strategy, many organizations have been looking into a few more phases or activities: identifying and monitoring performance measures, aligning budgets to the strategy, internal change management throughout the organization, and engaging the community and soliciting their buy-in before the strategy is approved. This renewed version of strategic planning is known as strategic management. The idea is to follow through the strategic planning approach on multiple fronts, not just on the development of the strategy. It brings the community and a stronger organizational perspective into the equation.

A New Decade, A New Opportunity, A New Approach

Fast forward to where we are today, the pandemic we are currently experiencing has put our organizations’ strategic capabilities to the test:

A community’s needs and expectations for services have shifted. Due to physical distancing, people prefer remote and contactless access. It is likely that the shift will continue as we reopen our economy. You may have already seen the need for new services, such as the business support service, that helps local businesses access government support programs.4 So our understanding and traditional way of serving may not be most relevant. It is important to understand the changing needs so we can better serve.

The world is connected and fuzzy. Our local communities and organizations are not immune to external shocks. We have seen places that have managed to watch emerging issues globally and have responded timely in their own ways.5 Those places not only created more lead time for themselves, but supported other communities in great need. It is important to have a better sense of the surrounding, so we can be more informed and less likely to be caught by surprise.

We have to address the above two points by bringing the organization together. Our organization is like a human body. It is crucial that the left hand knows what the right hand is doing. Leadership, prioritization, and accountability all play important roles in bringing the organization together. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Canadian Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam were role models of those qualities.

While the pandemic has affected us in many different ways, it can also be an opportunity to improve the way we develop strategies. In the last article, we introduced strategy management as a new approach and gave a few examples to demonstrate how it has assisted public organizations fighting the pandemic.6 Here, we would like to dive in and articulate three benefits of strategy management compared to strategic management:

1. Community-centric

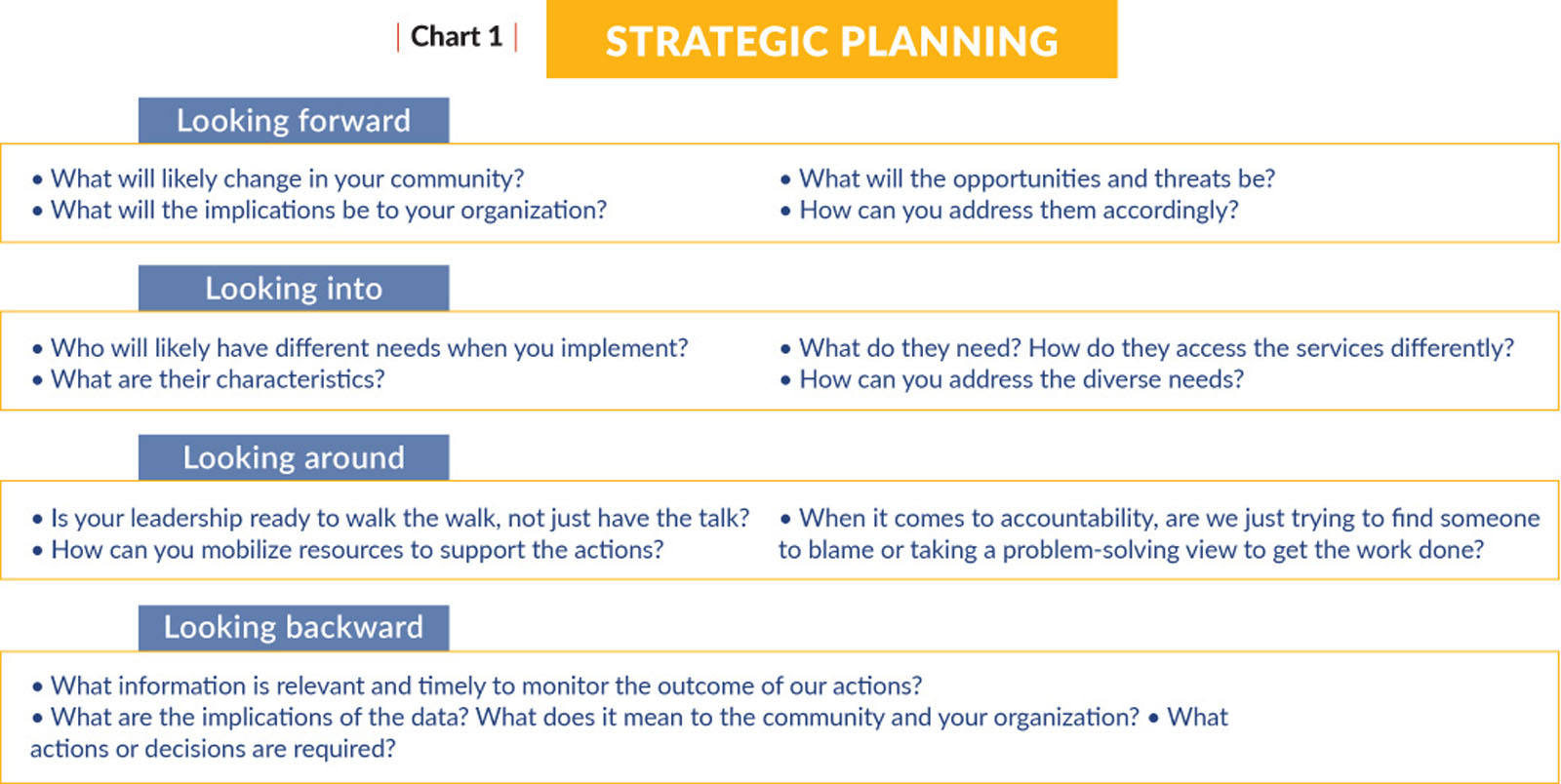

Community is front and center in strategy management. Strategy management focuses on developing organizational capabilities in “looking forward” to understand the changes in our community, in “looking into” our community to understand the diverse needs, and in “looking backward” to understand the implications to the community.

Under strategic management, community engagement tends to happen at the beginning of the development process. The engagement is based on a one-size-fits-all approach without recognizing multiple lines of services our organizations provide, and also without recognizing the diverse needs of the community in each line of service. In addition, the impact of our actions on the community are often overlooked.

2. A Two-way Approach

Strategy management values the input of frontline staff. While the project team leads the process to ensure the work is done properly, subject matter expertise is sought throughout the entire process because it is the best source of information when it comes to our community. Our front line staff are essential to the development and implementation of the strategy.

Under strategic management, the strategy is often developed between the project team and project sponsors (executives or council). Subject matter experts are brought in as needed. Because of the tight development process, after the strategy is approved, the project team or a separate team promotes the strategy within the organization and incorporates the strategy in employees’ performance planning and rewarding processes. Most of the communication is one-way.

3. Ongoing Development

Strategy work is not considered a piece of work that happens at a point in time under strategy management. The world is connected, the change is constant, and our community’s expectations are evolving; thus, the need to develop organizational capabilities to address those issues is ongoing. By that we mean each service area needs to change the way we do our work by developing a holistic view. The work should not be seen as just fulfilling a corporate ask that comes from the top. Developing organizational capabilities to answer those questions (see Chart 1) should also be the focus of our service areas—not solely the focus of the project team.

Under strategic management, the strategy work is a snapshot in time. By nature, each strategy has a life span valid for a limited period of time, but even so, the strategy can quickly become obsolete when the project sponsor is leaving the organization or the direction from council has changed significantly. Secondly, the development process is fairly lengthy. Depending on the size of your organization, the development and approval process can take anywhere from three to 24 months. It is possible that the information collected during the community engagement and environment scanning phases could become outdated by the time the strategy is approved.

Conclusion

We have gone through two iterations of strategy development approaches, moving from strategic planning to strategic management (see Table 1). Much of what Professor Poister predicted in 2010 has been realized7 and yet, new issues continue to arise: evolving community expectations, a call for an evidence-based approach, and a need to be more responsive and agile in strategy development. Just like Rome wasn’t built in a day, our work in strategy isn’t completed through a one-time effort. Moving from strategic management to strategy management is the next level of maturity (see Table 1). While the change from planning to management represents the need for a more proactive approach, the change from strategic to strategy represents the need for a more rigorous approach that is holistic, evidence-based, and timely.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, we have demonstrated our ability to innovate and adapt to changing conditions in a very quick turnaround. But how can we sustain the momentum and innovate organically over time? We don’t have a perfect answer to this yet, but strategy management could be the answer for your organization.

Endnotes and Resources

1 “Strategic Planning Revisited,” Kel Wang and Michael Sambir, PM magazine, August 2019.

2 Poister, Theodore H. 2010. “The Future of Strategic Planning in the Public Sector: Linking Strategic Management and Performance.” Public Administration Review : December 2010 Special Issue, ppS246–S255.

3 Vinzant, Douglas H., and Janet C. Vinzant. 1996. “Strategy and Organizational Capacity: Finding a Fit.” Public Productivity and Management Review 20(2): 139–57.

4 The city of Toronto has been providing this service since April.

5 See examples in “Look Beyond the Crisis,” PM magazine, June 2020, from the city of Surrey and Alberta Health Services in Canada.

6 “Look Beyond the Crisis,” Kel Wang and Michael Sambir, PM magazine, June 2020.

7 See endnote 2. Three predictions: (1) Shifting from strategic planning to strategic management; (2) moving from performance measurement to performance management; and (3) linking strategy and performance management more effectively.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!