“Whoever is detected in a shameful fraud is ever after not believed even if they speak the truth.” —Phaedrus, 370 BC

Spring Lake, North Carolina, is a small town of 12,000 residents just outside of Fayetteville, adjacent to Fort Liberty Army base (formerly named Fort Bragg). In 2022, the town received undesired national notoriety as their finance director was convicted of fraud and embezzlement. She embezzled more than $567,000 over five years for her personal use by either depositing it into her bank account or using it to pay for rent at the assisted living facility where her husband lived. Unbelievably, city checks were used to pay the rent and the husband’s name was listed in the memo section of the check. After the state auditor became involved, it was revealed the town has no record of over 25 vehicles that had been purchased for the town now either missing from fleet records or stolen. The town operations are now under state oversight.

It may be understandable when a corrupt individual strikes a small, understaffed community like Spring Lake, but scores of cities and counties of all sizes across the country with solid management teams and reputations have had scandals over alleged and realized fraud and embezzlement. A summary of recent embezzlement cases from internet news sources found over 650 alleged cases that were as high as $53,000,000 in Dixon, Illinois.

The Magnitude of the Fraud Problem

According to statistics from the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) 2022 Report to the Nations, fraud and embezzlement is on the rise. Recently, inadequate staffing levels and workplace changes due to COVID-19 responses and new technology may have contributed as former processes were disrupted. Fraud accelerates as system safeguards are set aside and control processes are stressed due to staffing turnover and remote work impacts. Every ICMA manager reading this should ponder their recent post-COVID operational changes, often made in haste or temporarily, to accommodate workplace and staffing changes.

According to the ACFE, the most common types of fraud committed in government are corruption, billing schemes, non-cash fraud (including asset misappropriation), payroll fraud, and expense reimbursement fraud. Half of all frauds are due to either a lack of effective controls or someone overriding existing controls without detection. Asset misappropriation represented 86% of all fraud in 2021, with a median loss of $100,000. The average loss to fraud increases dramatically to over $800,000 dollars when its duration exceeds five years. The average loss to government agencies is greater than other corporate entities and local government fraud cases averaged 123% higher in dollar loss than in state governments. Average dollar loss was similar whether the government had fewer than 100 employees or more than 10,000 employees.

Managers May Know and Trust the Perpetrator

The ACFE report also sheds light on the profile and techniques of the perpetrators of fraud. Sixty-two percent of all fraud was committed by management-level employees, with ages ranging from 31 to 50, and in 65% of cases, committed by someone with a college degree. The average loss per fraud is 150% greater and continues for twice as long a period when committed by a manager. Typically, 18-24 months pass before a government identifies and acknowledges that it has experienced fraud.

Half of all fraud cases are committed by a long-term trusted employee (25% with more than six years of employment and 20% with more than 10 years). These long-tenured employees steal almost three times more than less tenured perpetrators and are also more likely to collude with others and take longer to detect. The six most recent red flags associated with long-tenured employees are someone living beyond one’s means, having a close relationship with a vendor, having control issues, being unwilling to share duties with a peer, bullying or intimidation, and irritability or defensiveness. Typically, 85% of fraudsters displayed at least one of these six behavioral red flags.

Retroactive Annual Audits Are Insufficient in Protecting You

Most managers publicly promote and may believe that their annual audit will protect their jurisdiction’s and their own reputations, but according to the ACFE report, that is misplaced trust. When it comes to fraud prevention, “trust but verify” and “eternal vigilance” are better mantras. The ACFE report found that an external audit is associated with detecting fraud only 4% of the time. Good fiscal and inventory controls do assist in preventing fraud, but the most common control implemented after a known incident is “management review.” Therefore, it is more beneficial to proactively complete a fraud risk assessment to identify vulnerabilities before something happens. Proactive data monitoring and analysis is associated with the greatest reduction in the duration of fraud (56%) and a 47% reduction in the financial cost of the fraud experienced.

This article will assist managers in understanding the best practices to save you from experiencing fraud within your organization. The review in the previous paragraphs provides some solid statistical insights into fraud, but PM readers will benefit from hearing some of thoughts from interviews with two ICMA members who are familiar as both managers and recognized consultants on the best financial practices for fraud prevention: Kevin Knutson, ICMA-CM, is assistant county administrator of Pinellas County, Florida; and David Ross, ICMA-CM, is president of 65th North Group, a national government fraud risk consulting firm. The following questions were posed by Randall Reid, ICMA southeast regional director.

From your work experience, what do you see as the principal damage to organizations that have experienced fraud?

Kevin Knutson (KK): The rising rates of white-collar crimes, including fraud and embezzlement, should make every local government manager take note, as it is never just a financial issue.

Fraud also undermines public confidence and trust in the government. Fraud destroys reputations and the brand and self-image of communities. It has broader consequences for society and robs other programs of resources. It doesn’t matter if it’s perpetrated by internal staff or outside threats either. An increasing number of public organizations have experienced cyber fraud perpetrated by isolated hackers or highly sophisticated networks with links to organized crime and international drug cartels.

Local governments will require increasing use of data analytics and artificial intelligence tools in local government to prevent fraud and global-based cyber schemes through continuous monitoring and data integration. There will be additional continuing expenses to do this properly in addition to the occasional loss.

What are the best practices for proactive fraud risk mitigation that a local manager should employ?

David Ross (DR): The best fraud risk mitigation practices for government organizations are to begin with the mindset that the annual external audit does not protect you from fraud, nor is it designed to find your organization’s fraud and embezzlement risk vulnerabilities. Managers must never use trust as a control.

Many frauds in local government happen for years, after receiving several “clean” audit reports. External audits serve a valuable purpose, but fraud risk reduction is not one of them. All government fraud incidents happen in organizations with professional staff in place (many have been there for years), the organization received a clean (unqualified opinion) on their most recent external audit, and they have professional policies in place.

For most of these organizations, the fraud incident caught them completely by surprise. They didn’t realize they had vulnerabilities in their processes and the person who committed the fraud was a trusted employee. For managers, trusting employees is essential to support a positive workplace; however, trust must never be used as a control. Placing trust in someone to the exclusion of ensuring proper safeguards are actually in place (not just you thinking they are in place) is one of the top reasons why fraud happens in local government.

A comprehensive fraud and embezzlement risk assessment is one of the most important recommendations for local government leaders to identify vulnerabilities in existing processes. While it might be uncomfortable to complete an assessment because it will show vulnerabilities, not completing one means that all the vulnerabilities that exist will remain. It’s better to keep your eyes open, know what you are dealing with, and address vulnerabilities before falling victim.

The next best move mitigate risk is to ensure you are performing regular data analytics, at a minimum, on your employee purchases. Procurement systems are a top fraud scheme and advanced data analytics with professional monitoring of the data results is known to significantly reduce fraud risks and duration.

KK: Awareness of the potential for fraud, detection procedures, and clear prevention policies should be part of ongoing operational planning and performance management by the leadership team. Demonstrating that senior leaders are paying attention can alone reduce the risk of fraud and increase the potential for identifying unethical behavior. In our organization, we have assigned certain compliance and analysis functions to staff to ensure that there is appropriate analysis and oversight.

We must start with the attitude that “it can happen here,” and has. We all hope that nothing like that is happening in our organizations, but we can’t assume it. We also should not be afraid of asking the right kinds of probing questions when things don’t add up or our intuition suggests something is awry.

What are the differences between an “annual audit” and a fraud risk assessment?

DR: An annual audit looks at whether funds are recorded properly in all the right buckets (whether the organization presented its financial statement information fairly and in accordance with U.S.-accepted accounting principles). There is often limited sampling of certain controls (such as purchasing or payroll), and it looks back in time to see if those limited samples reveal any issues.

A fraud risk assessment is forward-looking based on existing practices and policies. It is a means to identify vulnerabilities that expose the organization to fraud, regardless of whether someone has exploited those vulnerabilities in the past.

Joy Tozzi, township administrator of Robbinsville Township, New Jersey, states it well. “An audit only takes you so far. It provides a snapshot of where you were, and its focus is on its financials. A fraud risk assessment is an overall risk assessment of the entirety of your organization. It takes a deep dive into your practices and shows you where there are potential vulnerabilities and makes recommendations regarding policies and procedures, asset management, and cyber security vulnerabilities. Once the assessment is completed, any threats to your organization have been greatly reduced.”

KK: An audit is designed to ensure that what’s in your financial statements can be reasonably assumed to be accurate, not whether the transactions were appropriate. Working as a consultant, I have stumbled across fraud where all the financial paperwork was executed and passed a financial audit, but the work was either not completed or the materials were used for other purposes. In one example, an employee was building a vacation home out of materials purchased by his agency.

We recognized that many types of fraud by insiders will look legitimate on the surface—appropriate paperwork and proper documentation on the general ledger—so there is no way to catch it through an annual audit. We wanted to ensure that we had better ways to detect potential fraud and make it difficult for anyone to find a way to misuse taxpayers’ money.

What are the dangers of dependence on your annual audit when it comes to fraud risk?

DR: Solely depending on an annual audit for fraud risk identification, which was never designed to identify fraud risks or vulnerabilities to fraud within the organization, has been disastrous for local government managers. Only a fraud risk vulnerability assessment will comprehensively identify vulnerabilities to fraud within the organization. Ask any of the hundreds of current or former managers in local government whose organization fell victim to a multi-year fraud after having received multiple clean audit reports.

Where do you begin if you want your organization to be better protected and what are some sources of assistance for managers?

DR: Once you’ve identified your vulnerabilities, it is important to begin addressing them in a systematic manner. A good assessment will prioritize recommendations with the knowledge that there are only so many employees to implement them, and money can be a factor as well. Certain audit or CPA firms can complete fraud risk assessments; however, while not taking away from their work, it is best to ensure that whoever completes the fraud risk assessment is highly trained in internal controls within a government setting, is knowledgeable about government operations, is a certified fraud examiner, and ideally has completed numerous fraud risk vulnerability assessments in the past. An in-house employee with this level of training or a consultant specializing in fraud risk assessments will help ensure your needs are met.

KK: After uncovering an instance of fraud in our organization that went undetected until we received a tip from the public, we decided to conduct a comprehensive risk assessment to accomplish two main goals. First was to see if there were other areas where we might be unknowingly experiencing fraud, and second, to identify gaps in our policies and procedures that could be exploited by bad actors. As part of that effort, we have looked at recommended practices from the Government Finance Officers Association, the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, and the Institute for Internal Auditors.

What are the widespread problem areas or specific assessments to consider in reducing fraud vulnerabilities?

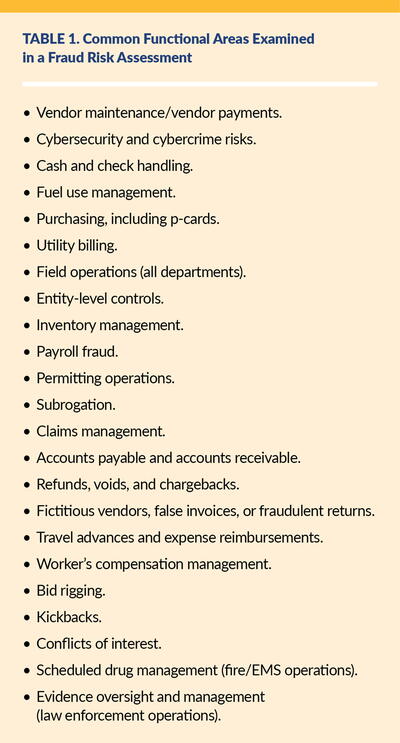

DR: Organizations should consider their needs and decide whether to complete an assessment of all functions or a limited number of functions. Simply put, any internal processes, point of customer interaction or payment, inventory storage or distribution center, fleet maintenance, property or equipment acquisition, and any automated systems could be appropriate, as could a review of a department organizational unit. Common functional areas looked at during a fraud risk assessment are included in Table 1.

What frequency for assessments is most effective?

DR: In addition to an initial comprehensive fraud/embezzlement risk reduction assessment, annual follow-up assessments are also highly beneficial since computer systems change, employees change, fraudsters are always coming up with new ways to steal, and employees have been known to override controls.

Performing monthly disaggregated data analytics of purchases, including p-cards, is a fantastic way to reduce purchasing risks by identifying risky vendors and risky employee purchase transactions. It is amazing what disaggregated data analytics can do as they create a picture that a good fraud examiner can look at that isn’t otherwise visible when just looking at raw purchasing data each month.

Once a risk assessment is completed, how should this information be shared with elected officials?

DR: This is something that is best left to each organization; however, as a rule, it is appropriate for elected officials to be aware that a fraud and embezzlement risk assessment is being completed. These assessments serve several important purposes that elected officials and constitutional officers often find valuable:

- They identify fraud and embezzlement risk vulnerabilities not previously known.

- They are a best practice.

- They create accountability in operations.

- They improve resident trust in employees and operational performance.

- They significantly reduce risk of a multitude of different types of fraud schemes that could occur or go undetected.

What considerations are appropriate when considering a fraud risk vulnerability assessment in house versus using a consultant?

DR: It all comes down to the level of knowledge and expertise by the in-house employee. If they are a certified fraud examiner who is trained and knowledgeable in conducting a comprehensive fraud and embezzlement vulnerability assessment, then it can be appropriate to use in-house employees. Then it comes down to whether these employees have the time to complete the assessment and author the report with recommendations. A typical assessment takes approximately three months to complete. If cost is a factor, a good consultant can often do the work much more cost-effectively than in-house employees, when considering salary and benefits.

KK: For our organization, getting expertise from the outside was critical because of the size and complexity of our operations, but also to ensure that it was “arm’s length”—that no one in a position to commit fraud participated in the analysis. Most county governments collaborate with constitutional officers and internal auditors cooperatively to identify and schedule when system or departmental assessment reviews should occur and contract external assistance if needed. We have the good fortune of having an internal auditor function that can conduct specific investigations and reviews of individual processes, where many other organizations would benefit from outside help for those kinds of activities as well.

What training can assist internal staff with completing an in-house assessment?

DR: The best training is taking steps to become a certified fraud examiner who specializes in government operations. Obtaining this certification can take years, depending on the employee, but this is the best place to start. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners has resources available that include a fraud resource library and training courses that will be of benefit to anyone working on a fraud risk assessment.

ICMA managers reside in numerous countries around the world, and while ethics and laws vary, do you see risk assessment innovations outside of the United States?

DR: As a former police officer, I know fraud is an international problem, and the response to fraud vulnerabilities in each country is different based on their laws and culture. The UK is in the process of making “failure to prevent fraud” a criminal offense. The law would make it a crime for an organization’s leaders to not have “adequate” and “reasonable” controls to prevent wrongdoing.

The fraud problem in the United States for local government is getting worse and it may only be a matter of time before similar action is taken here. Regardless of the possibility of a new law being enacted, this should be about taking proactive measures to reduce risk and protect the organization, its employees, and taxpayer money.

Are there other advantages of risk assessments over audit dependency for local governments?

KK: Risk assessment can be a critical component and catalyst for a continuous improvement effort in your organization and can improve operations, reduce waste, or streamline processes. Maryann Ustick, city manager of Gallup, New Mexico, shared how her community benefited. “We contracted and conducted a fraud risk assessment for internal service departments in Gallup. The outside consultant’s report provided invaluable information that enabled the city to revamp processes and procedures to significantly reduce the risk of fraud especially in our financial and procurement processes. This risk assessment not only assisted the city in developing procedures and processes to reduce the risk of fraud, but it also uncovered very serious deficiencies in the city’s warehouse, which resulted in a complete overhaul of staffing and procedures. The outcome resulted in eliminating potential fraud, but also resulted in a much more efficient and effective warehousing system.”

While audits focus on procedural compliance, a quality risk assessment review can bring a positive perspective and process to build awareness and solicit input. Supporting this viewpoint is Sharon Gilman, deputy county administrator of Cochise County, Arizona. “The fraud risk assessment is an amazing tool for improvement, especially since it is not intended to look backward, but rather forward to raise awareness within our organization of how we can better protect our employees and the organization as a whole.”

Additionally, Catherine Traywick, Cochise County treasurer, states, “I recommend that other governments look at a similar study on their own operations. We have already implemented several recommendations from our internal control and fraud/embezzlement risk reduction study. My office, my employees, and of course, our taxpayers’ money are much safer due to following our consultant’s recommendations.”

How should managers prepare for artificial intelligence (AI) and how will it impact fraud prevention?

KK: For most managers, the first step is awareness of AI’s potential and how it will be phased into analytical software we are presently using in local government. According to the ACFE, AI will increasingly assist cleaning and compiling data, preparing it for faster analysis, generating and analyzing networks, identifying anomalies, and scoring for potential fraud, error, and abuse. It should furthermore efficiently identify potential fraud, scenario prioritizing, and comprehensive documentation.

Confronting Fraud Is in ICMA’s DNA

The history and purpose of our profession, arising out of the early progressive reform movement, was in large part to fight municipal corruption. Preventing fraud is in our professional DNA. Research from Dr. Kim Nelson at the University of North Carolina shows that the form of government does matter in this regard. Her findings “indicate that municipalities with the council-manager form in North Carolina are 57% less likely to have corruption convictions than municipalities with the mayor-council form.” Our ICMA Code of Ethics also requires us to set exacting standards of integrity to safeguard and protect public resources. This must be routinely reinforced among all our employees, particularly the long-tenured, who we may trust completely. At the personal and global level, an ethical culture will fortify and assist compliance where accountable systems are assessed and proactively evaluated.

Preventing Fraud with a Culture of Accountability

The Fraud Triangle (seen in Figure 1) demonstrates that to commit an act of fraud, someone experiences pressure (often financial), they then rationalize their action, and there must be opportunity to do so. Organizational cultures can help address pressure. Ethics and values training can reduce self-serving rationalization. However, reducing opportunity is where local government leaders can make the biggest impact to minimizing their risk. This means a fraud may not start with the perpetrator intending to profit from it, but that those involved gradually read the possibilities, and then develop and refine the fraud over time.

The fact that fraud and embezzlement remain a growing problem within our organizations is a clarion call for a more robust focus on their elimination and prevention. Portraying our unqualified annual audits as a flag of purity in our operations is a surefire way of setting ourselves up for embarrassment. As ICMA managers, we need to embrace creating a culture of accountability and continuous improvement to prevent fraud. A culture where we use proactive risk assessment, strategically update policies aligned with technology and workforce changes, and utilize modern disaggregated data analytics to routinely manage records, test our systems, and verify that checks and balances are in place will protect public resources and remove temptations from our employees during these socially and economically stressful times.

RANDALL REID is southeast regional director of ICMA (rreid@icma.org).

DAVID ROSS, ICMA-CM, is president and CEO of 65th North Group, LLC (dross@65thnorth.com).

KEVIN KNUTSON, ICMA-CM, is an assistant county administrator for Pinellas County, Florida (kknutson@pinellas.gov).

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!