The last few years have been eventful to say the least. Social unrest. Mass shootings. A financial meltdown. A pandemic that forced many first responders to sleep in their cars or at hotels for fear of infecting their children or others in their home. The same pandemic that would kill friends, colleagues, and others in their community or that filled the emergency room and hospital beds to a breaking point. And a belief that our first responders must somehow perform above it all and without intervention. Our message to them is often “It is not okay to not be okay.”

Scope of the Problem

Two years ago, I stood on the National Mall in Washington, DC, as names were read of police officers who died in the line of duty and that will now be added to the National Police Memorial Wall. Their families were escorted in, many with tears in their eyes as hundreds of officers were saluted. Candlelight would eventually light the mall as a thin blue laser shot into the night.

It is a sad fact that police officers are more likely to die from suicide than in the line of duty. In 2020, 116 police officers died by suicide while 113 died in the line of duty (Stanton, 2022). In 2021, that number rose to 150 officers dying by suicide. Tragically, law enforcement officers have a 54% increase in suicide risk compared to the civilian population.

No department is immune. The problem seems to be even worse in smaller departments, which may not have an extensive support system or peer support resources. A 2012 study published in the International Journal of Emergency Mental Health found that departments with fewer than 50 full-time officers had a suicide rate over triple that of departments that had over 500 full-time officers. This is concerning, as 49% of the police departments in the United States employ less than 10 full-time officers.1

The number of firefighter suicides is estimated to be at least 100 per year. According to the Ruderman White Paper on Mental Health and Suicide of First Responders, the suicide rate for firefighters is 18 per 100,000 compared to 13 per 100,000 for the general public. The Ruderman research showed an increasing number of firefighters are dying by suicide as a result of suffering from behavioral health issues—including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—from exposures that they have suffered while delivering emergency services to the public. The paper concluded, “There is a lack of culturally competent behavioral health specialists to assist firefighters and local employee assistance programs are ill-equipped to assist first responders.

Personal Story

Suicide and mental health issues have become a significant crusade for me since I returned home in May 2016 to find my husband dead by suicide. At the time, friends, family, and I saw no warning signs that indicated he had contemplated taking his life. He was the life of every event, the sought-after stylist for pageants and events. People sought his counsel when planning productions, thus he found himself actively engaged throughout the Washington, DC area and even outside the United States.

It was only after his death that I began to look at his personal journals and emails that he had sent to me and various friends and began to notice a pattern. This was the same pattern demonstrated by others that we have lost to suicide, such as Robin Williams, Kate Spade, and Anthony Bourdain. Undiagnosed depression hidden by a façade had led others to believe there was no possibility of such a demon hiding within.

I was lucky in many ways because of professional friends, acquaintances, and national efforts at preventing suicide being located nearby in the Washington, DC area. A good friend called me about three weeks after Barry’s funeral and invited me to a group of survivors of suicide. It was through that involvement that I became active with the DC Chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

You can imagine my shock when I attended classes that described warning signs that repeated nearly word for word what my husband had expressed in journals, in emails, and even that he would laugh and exclaim to me. As a stylist, he spent hours making sure every hair was perfect in his look, adding various potions and lotions to ensure a healthy head. But in the weeks leading up to his death, he abandoned both—one of the signs we talked about with experts.

Warning Signs

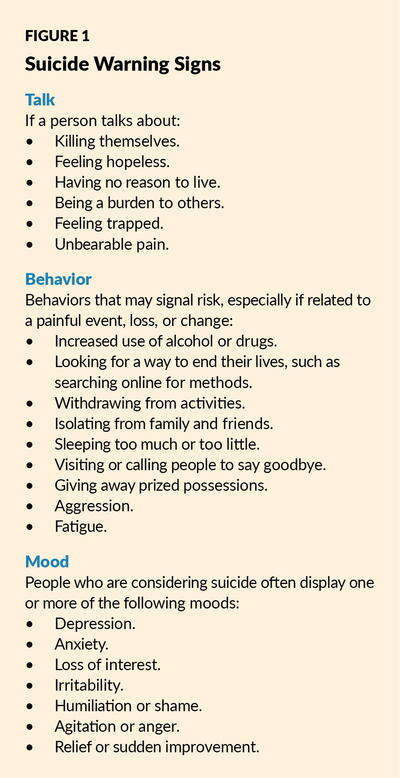

The following warning signs do not necessarily mean someone has decided to take their own life, but may be indicative of mental health problems that could build up to that point.

Something to look out for when concerned that a person may be suicidal is a change in behavior or the presence of entirely new behaviors. This is of most concern if the new or changed behavior is related to a painful event, loss, or change. Most people who take their own lives exhibit one or more warning signs, either through what they say or what they do. See Figure 1 for the full list of warnings signs, such as those found in one’s way of speaking, behavior, and mood.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Firefighters and other rescue personnel develop PTSD at a similar rate to military service members returning from combat, according to a 2016 study from the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. The report reveals that approximately 20% of firefighters and paramedics meet the criteria for PTSD at some point during their career. This compares to a 6.8% lifetime risk for the general population. The connection between PTSD and traumatizing rescue work is clear. In fact, the FBI launched the Law Enforcement Suicide Data Collection in 2022 to help improve understanding and prevent suicide among law enforcement officers.

What Is PTSD?

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a disorder that develops in some people who have experienced a shocking, scary, or dangerous event. It is natural to feel afraid during and after a traumatic situation. Fear is a part of the body’s “fight-or-flight” response, which helps us avoid or respond to potential danger. People may experience a range of reactions after trauma, and most people recover from initial symptoms over time. Those who continue to experience problems may be diagnosed with PTSD.

Who Gets PTSD?

Anyone can develop PTSD at any age. This includes combat veterans and people who have experienced or witnessed a physical or sexual assault, abuse, an accident, a disaster, or other serious events. People who have PTSD may feel stressed or frightened, even when they are not in danger.

Not everyone with PTSD has been through a dangerous event. Sometimes, learning that a friend or family member experienced trauma can cause PTSD.

According to the National Center for PTSD, a program of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, about six out of every 100 people will experience PTSD at some point in their lives. Women are more likely to develop PTSD than men. Certain aspects of the traumatic event and some biological factors (such as genes) may make some people more likely to develop PTSD.

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of PTSD?

Symptoms of PTSD usually begin within three months of the traumatic event, but they sometimes emerge later. To meet the criteria for PTSD, a person must have symptoms for longer than one month, and the symptoms must be severe enough to interfere with aspects of daily life, such as relationships or work. The symptoms also must be unrelated to medication, substance use, or other illness.

The course of the disorder varies. Some people recover within six months, while others have symptoms that last for a year or longer. People with PTSD often have co-occurring conditions, such as depression, substance use, or one or more anxiety disorders.

After a dangerous event, it is natural to have some symptoms. For example, some people may feel detached from the experience, as though they are observing things rather than experiencing them. A A mental health professional who has experience helping people with PTSD, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, or clinical social worker, can determine whether symptoms meet the criteria for PTSD. Cognition and mood symptoms include:

- Having trouble remembering key features of the traumatic event.

- Having negative thoughts about oneself or the world.

- Having exaggerated feelings of blame directed toward oneself or others.

- Having ongoing negative emotions, such as fear, anger, guilt, or shame.

- Losing interest in enjoyable activities.

- Having feelings of social isolation.

- Having difficulty feeling positive emotions, such as happiness or satisfaction.

Cognition and mood symptoms can begin or worsen after the traumatic event. They can lead a person to feel detached from friends or family members.

The Gorilla in the Room

Police, fire, and EMS employees have faced and continue to face unprecedented situations. Gun violence and death have reached epidemic proportions in many of our cities and communities. School shootings involving multiple victims are not limited to urban areas but have been shown to occur in rural, urban, and suburban areas with an ever-increasing frequency.

Dealing with communities that have experienced gun violence at shopping centers, synagogues, religious places of worship, or even parades challenges anyone. First responders have to witness firsthand the carnage that has taken place. Talking to a responder at one of these events, they explained they were totally unprepared to see a young victim that was rendered unidentifiable, and it was made worse because their own child had an outfit like that worn by the victim.

As a former chief, it brought back memories of when we were called to a scene in which two beautiful children and a mother died in a house fire that was of suspicious origin. Two of my paid-on-call firefighters came in the following day and turned in their gear, tears in their eyes, as they explained what it was like to recover one of the bodies, which had been wearing a sleeper like their own child.

And what did we usually do in those cases or other traumatic events? Often we told people it was not okay to not be okay and to just get back to work.

If someone expressed emotional or mental health problems, they often feared (and were) labeled as unfit for duty or certainly for promotion. It reminds me of the trauma many World War II veterans may talk about but that they stuffed inside for the last 70 years.

We must make our workplaces a safe space to say I’m not okay.

We should also have the expectation of grief in many situations and help our teams work through that grief process. The stages are not always linear; people will often regress, move ahead, take several steps back, and often get locked into an area. It is important to have policy, process, and experts identified that can help your team and staff during and after traumatic events.

And those events do not have to include death. Communities in Florida remain traumatized by the damage and destruction caused by last year’s hurricane. I have a good friend who was a manager on the Florida coast that can tell you the struggles he and his team had following Hurricane Katrina.

Risk Factors and Protective Factors

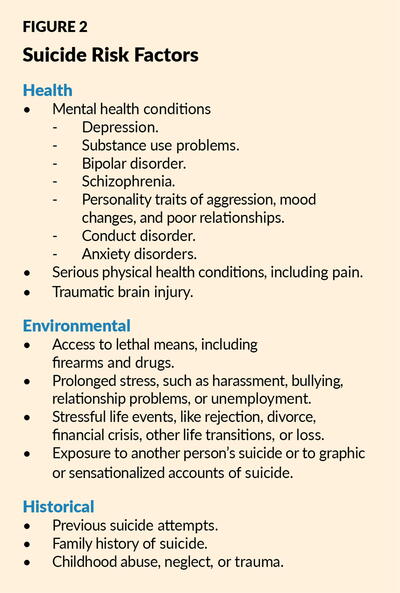

What are the risk factors that may increase the chance that a person’s mental health crisis will lead to death by suicide? Risk factors are characteristics or conditions that increase the chance that a person may try to take their life. See Figure 2 for the full list of suicide risk factors, including environmental, historical, and those related to one’s health.

While risk factors increase the chance of suicide, protective factors help to decrease that risk. Protective factors include the following:

- Access to mental health care and being proactive about mental health.

- Feeling connected to family and community support.

- Problem-solving and coping skills.

- Limited access to lethal means.

- Cultural and religious beliefs that encourage connecting and help-seeking, discourage suicidal behavior, or create a strong sense of purpose or self-esteem.

Resources

There are many resources that can aid your team; many that are no cost:

- Every state has at least one chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. You’ll find various classes that are offered in person or online and deal with looking for symptoms, assisting survivors, dealing with youth and teens, working with a military community, LGBTQIA+ community, schools, etc.

- The International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) is working with researchers at Texas A&M College of Medicine and Baylor Scott & White Healthcare to offer new resources for IAFF members dealing with the tragic loss of a fellow brother or sister to suicide. 5

- The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) created The National Consortium on Preventing Law Enforcement Suicide, a group of multidisciplinary experts with a common goal of preventing officer suicide. Convened by the IACP, the consortium focuses on solutions to emerging challenges and successes of the field in addressing mental health and preventing officer suicide. 6

- The 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (formerly known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) provides free and confidential emotional support to people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, across the United States. The lifeline is comprised of a national network of over 200 local crisis centers, combining custom local care and resources with national standards and best practices. 7

Conclusion

First responders, along with all of our public safety personnel, need to know that their organization is behind them and ready to assist in all aspects of their mental health. The stigma of mental health in this profession is no longer tolerable, but this message must come from leadership. We owe it to our employees to educate ourselves and each other on the warning signs and risk factors of suicide ideation, the signs and symptoms of PTSD, the stages of grief, and most importantly, the mental health resources available to those in need.

TOM WIECZOREK is director of the Center for Public Safety Management, LLC. He is an expert in fire and emergency medical services operations. He has served as a police officer, fire chief, director of public safety, and city manager, and is former executive director of the Center for Public Safety Excellence.

Endnote

1 Volanti JM, Andrew ME, Burchfiel CM, Dorn J, Hartley T, Miller DB (2016) Posttraumatic stress symptoms and subclinical cardiovascular disease in police officers. Int J Stress Manag 13 (4):541–554.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!