The metropolis of Mumbai is the capital of the Indian State of Maharashtra. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-most inhabited city in the country after Delhi and the seventh-most inhabited city in the world, with a population of roughly 20 million.

According to the 2011 census, the population of Mumbai city was 12,479,608. The population density is calculated to be 20,482 persons per square kilometer, with living space at 4.5 sqm per person. The total number of slum-dwellers is calculated to be nine million, up from six million in 2001, so 62 percent of all Mumbaikars (inhabitants of Mumbai) live in informal slums. Looking at that kind of densification in the city, particularly in slums, it becomes difficult to manage any type of calamity, disaster, or pandemic.

Just as in the rest of India, the COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged Mumbai. As of June 29, 2021, Mumbai has had 721,516 cases since the beginning of the pandemic, with a death toll of 15,426. But those numbers could have been much worse had it not been for the Mumbai Model, a series of initiatives taken by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), Mumbai’s top civic body, under the leadership of City Commissioner Iqbal Singh Chahal.

Mumbai is regarded as India’s financial capital, so the impact of the pandemic on the economy was of great concern as well. There was a surge with Mumbai’s decision to loosen up limitations following three months of the severe lockdown that was proposed to control the spread of the infection. On June 8, 2020, after the first peak, shopping centers, public parks, and workplaces were permitted to open. Prior to that, shops, commercial centers, and transport administrations had all been under lockdown. Experts say that there could have been no other alternative except lifting the lockdown, which demanded a huge financial cost for the country.

Millions have effectively lost their positions and vocations, factories were closed, and the fear of hunger drove masses of daily-wage migrant workers to flee cities, mostly on foot because public transport was halted overnight. A large number died of depletion and starvation. The expectation—which likewise urged the public authority to lift the lockdown—was that the majority of India’s undetected contaminations would not be sufficiently extreme as to require hospitalization. However, the number of rising cases shows that the city had an urgent need to take action.

First Wave

Based on a report by Azman Usmani, the first wave of COVID-19 in Mumbai was at its highest at the end of May 2020. Looking at figures in April and May, it was getting scarier day by day. Observing the peak, there was definitely something to be worried about.

The rise in the number of cases also resulted in a rise in the number of deaths. The situation was not under control, and people were dying due to inadequate medication facility, a lack of proper consultation, and a lack of appropriate public awareness. From March to mid-August, there was a tremendous increase in the number of cases. Putting a strict lockdown into effect resulted in a subsequent decline in cases from the end of August through the end of September.

We continued to track COVID-19 throughout the rest of 2020. After September, the intensity of cases seemed comparatively less. All festivals, such as Navratri, Diwali, and Christmas, were celebrated at individual homes rather than in public, as the city had restrictions in place set by the municipal corporation as a way to stop the spread of the virus in the city.

Second Wave

The second wave, which started on February 7, 2021, with 414 daily cases, continued to rise and reached to 9,792 daily cases on April 4, 2021, an increase of over 20 times the amount of active cases. Many discussions were held in Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), and City Commissioner Iqbal Singh Chahal was put in charge of managing the pandemic.

On April 16, 2021, BMC was hit with a surge of cases. Six hospitals under its administration were at risk for running out of oxygen, putting the lives of patients in danger. From 1:00 a.m. until 5:00 a.m. the following morning, under Commissioner Chahal, the BMC arranged ambulances to move patients to various emergency hospitals across the city.

The fact that Mumbai is a commercial hub with a high population density with many residents taking public transportation led to a severe spike in number of cases in the second wave. Hospitals in the city reported continued shortages of medical oxygen, patients struggled to find beds, and social media was flooded with messages for help.

The Mumbai Model

BMC’s management of the second wave, under the leadership of the municipal commissioner, is a prime example of leadership in crisis. Commissioner Chahal who took control of the situation by having a strategic mix of decentralization, augmenting infrastructure, and keeping a close watch on the loopholes in order to plug them. Decreasing from 12,000 daily cases to 2,000 daily cases, BMC played major role and did a commendable job under the leadership of the city commissioner.

The efforts of BMC have been applauded by the Supreme Court of India and referred to other states to adopt and follow. The commissioner and his team credit the combination of multiple initiatives that helped Mumbai fight COVID-19 impactfully. It takes a strong determination to wade through a crisis and turn the situation around, particularly in public systems such as healthcare. There are so many influencing factors that mostly lie outside of a municipal corporation’s control, yet to predict them and strategize for creating a visible impact needs fine planning, systems thinking, quick decisions, intrinsic motivation, and team spirit. Proper planning and management with attention to detail and linkages is the key. The municipal commissioner started by visiting the hospitals himself. He visited Dharavi, the biggest slum in Mumbai, and evaluated the criticality of the situation with respect to supplies. Such on-the-ground evaluation led to some key insights relative to the first wave. During the first wave, people were more patient, took precautions, and were careful in their interactions and movements. It was observed that during the second wave people were getting edgy and restless, and were not adhering to the preventive behaviors. Once hit with a surge in the pandemic, they pressed their panic buttons and wanted relief instantly.

At this point in time, BMC already had a central control room, which was flooded with frantic calls for beds, oxygen, and so on. At one point in time, around 10,000 people were looking for medical care.

The municipal commissioner, along with his team, began working relentlessly by decentralizing everything. The commissioner created war rooms for immediate action, and planned in detail for patient admission, medical services, patient recovery, and in case of death, a proper system of disposal of dead bodies.

Across all 24 wards, wars rooms were created, which served as control centers where doctors, medical interns, and professionals provided data to be fed into the tracker, which gave the BMC a real-time picture of available resources. Each ward has a war room with 10 dashboards with information about hospitals and availability of infrastructure facilities. Thirty telephone lines, 10 telephone operators, 10 doctors with medical staff, and 10 ambulances to take patients to hospitals were manning the war room in three shifts and were available 24/7.

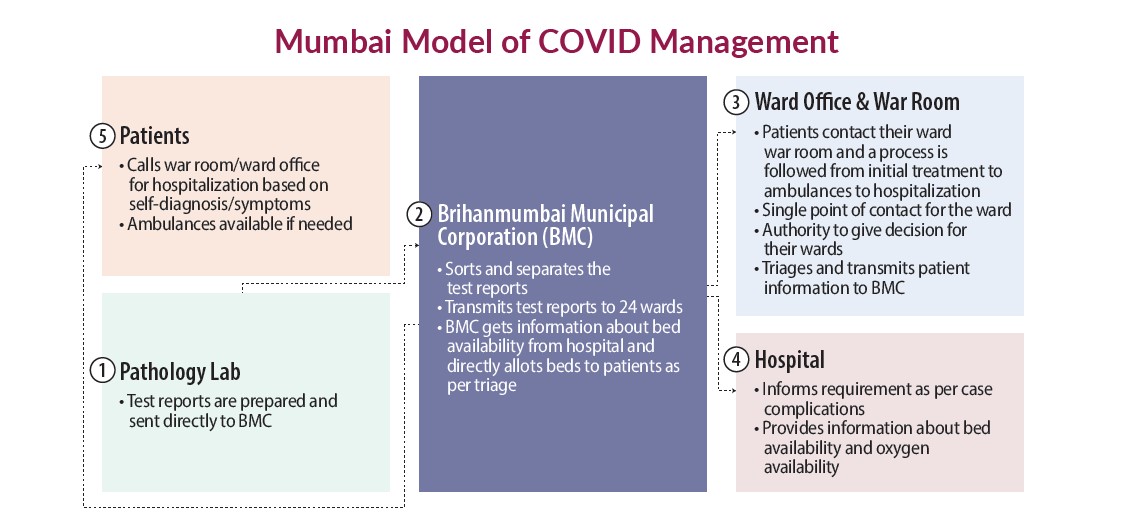

As reported by Mumbai television channel News 18, in the hub and spoke model of service delivery (as shown in the figure below) the BMC head office acted as a hub that received and sorted nearly 10,000 reports coming in from 55 testing labs every day and transmitted them to 24 wards. This kind of sorting enabled the ward to cater to their specific population cases, which reduced the load to approximately 400 reports per ward.

Patients contacted their respective ward war room and then followed the process from the war room to initial treatment to ambulance to hospitalization. Ward offices became a single point of contact for COVID-19 patients and were given authority to make quick decisions for the patients of their ward. This is an example of decentralization with appropriate devolution for achieving the outcomes at ground level.

Resource Efficiency

Various strategies for resource efficiency were deployed to make up the deficiency in the appropriate number of ambulances to ferry patients with medical care. Over 800 SUVs were refurbished and converted into makeshift ambulances with a partition between driver and patient. This led to quicker movement of critical patients to hospitals. The ride service company Uber loaned its backend technology to BMC for tracking ambulances closest to patients to minimize turnaround time.

Over 800 junior doctors and nurses, especially fresh graduates from medical colleges and nursing schools, were deployed in hospitals with appropriate remuneration as stipends. They were mobilized and stationed at hospitals and war rooms and were lodged in hotels at walkable distances from their war rooms, along with the best of safety practices.

A special team of professionals were assigned as a crisis team that closely monitored critical hospitals and their requirements. They made sure oxygen was in apt supply at all times, and supplies were arranged with appropriate information flowing from the BMC hub. BMC’s centralized dashboard monitored 172 hospitals, which made available 80% of beds and COVID facilities, including many jumbo centers set up in open grounds, along with government and private hospitals. The allocation of beds happened through triaging in a centralized manner from the BMC hub across Mumbai, where patients were allotted hospitals depending on severity and chances of recovery instead of a first-come first-served basis. The temporary structures, which were erected overnight, had every facility, from an intensive care unit to ventilators to oxygen beds. Additionally, over 65,000 beds were made available for isolation.

BMC allowed patients to walk into any of the seven jumbo centers set up across the city to be tested or admitted directly, without waiting for swab tests and results. Mr. Chahal says over 20,000 people have visited these facilities. In the Dharavi slum, around one million people live in a 2.5 square kilometer sprawl, making it not only very densely populated, but the largest slum in Asia. Managing COVID-19 in such a sprawl is quite challenging, so BMC adopted a “screen, test, and isolate” model for Dharavi. Fever clinics were set up, along with mobile testing vans to cover narrow alleys. Similar vans were deployed for making announcements and creating awareness about symptoms and location of fever clinics. Since May 10 after the surge, Dharavi has witnessed a daily drop in cases.

Crematoriums

As reported by Express News Service, the municipal commissioner worked with the Indian Institute of Technology to create an online dashboard of Mumbai’s crematoriums. The city has 46 traditional and 11 electric crematoriums, along with 18 gas pyres. Real-time information about availability of slots to cremate the deceased were provided to relatives who could then book the slots. A helpline number was also established through which relatives can acquire the slot for cremation, thus reducing chaos and long queues at the crematorium.

Preparing for the Third Wave

According to Times of India, the second wave is very much under control, with the daily case load of the city falling below 1,000 cases per day as of May 27, 2021. Preparing for the future—as it is observed that a third wave is likely to happen in July—Commissioner Chahal says 5,500 beds, including nearly 3,000 oxygen beds, are vacant. These include nearly 2,000 ICU beds with oxygen and ventilators. Four more jumbo centers are being set up, which will further increase patient capacity by 2,000 beds, including 200 ICU beds. In effect, Mumbai has 22,000 beds today and that capacity will go up to 30,000 beds in three weeks.

BMC plans to hand over each of these jumbo centers to be run by large private hospitals, along with five-star hospitals like Hinduja for patients who want to be treated with luxurious facilities. This is expected to augment the capacity of beds of well-off Mumbaikars. Along with this, a decentralized system for vaccines and drive-in centers for vaccinations are also being planned.

These incredible management interventions of strategizing resource sufficiency, demand-based resource allocation, decentralized management units, centralized allocation, and use of technology for information dissemination at appropriate levels led to Mumbai’s COVID-19 positivity rate to come down to eight percent. The city and the rest of the state of Maharashtra have been under severe restrictions since April 14. The restrictions are likely to be eased once the positivity rate further drops below five percent.

The Mumbai Model is a successful combination of multiple initiatives that were undertaken, albeit late in the pandemic, but as the saying goes, better late than never. All of this was possible because of the grit and determination of city leaders like Municipal Commissioner Iqbal Singh Chahal, who in spite of the severity of the problem and extensive criticism, never lost his hope to turn around a public health crisis for a densely populated and diverse city like Mumbai. When leaders take on a crisis as a challenge rather than just being impacted by it, cities witness change with positive outcomes.

DR. MERCY SAMUEL is associate professor, Faculty of Management at CEPT University in Ahmedabad, India.

HIMADRI PANCHAL is a teaching assistant at CEPT University in Ahmedabad, India.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!