By Gerald Cliff

A direct result of the ever-increasing reliance on technology and the Internet is that governments at all levels are rapidly becoming dependent on these technologies for provision of essential services. The downside to this reliance is that it magnifies the risk of cyberintrusions and data breaches.

These breaches can result in the compromise of personally identifiable information (PII) of every resident whose name, date of birth, and Social Security number reside on a local government server. Governmental entities also maintain records of personal health information (PHI) pertaining to their employees that, if compromised, could expose employees to serious problems.

Data breaches from phishing, hacking, and insider threat are on the increase and causing considerable damage in terms of costs to seal the breach and address the potential damage to those whose PII has been compromised. Here are examples:

In April 2015, the Florida Department of Children and Family Services (DCF) suffered a data breach when a state employee used the employee's employment-related access to obtain the personal information of thousands of Floridians.

According to the Department of Economic Opportunity (DEO), one of its employees managed to access the Florida Department of Children and Families' Florida ACCESS system. He then obtained the names and Social Security numbers of more than 200,000 people in the DCF system. In March 2015, the DEO employee was arrested and charged with alleged trafficking and unauthorized use of PII.

In May 2016, more than 100 Los Angeles County employees fell prey to a phishing scam, revealing usernames and passwords that were then used to disclose personal information of approximately 756,000 individuals who had done business with county departments.

The 2016 IBM Cost of Data Breach Report finds the average consolidated total cost of a data breach grew from $3.8 million to $4 million. The study also reports that the average cost incurred for each lost or stolen record containing sensitive and confidential information increased from $154 to $158 per record.

Ransomware on the Rise

Crypto-ransomware attacks software that encrypts a victim's data and then offers to sell the victim the decryption key are on the rise and have already crippled hospitals, police departments, educational systems, critical municipal infrastructure, and other vital cornerstones of the public sector. Examples include:

- An April 2016 ransomware attack against the Lansing Michigan Board of Water and Light crippled the agency's ability to communicate internally and with its customers, and ultimately cost the city-owned utility about $2 million for technical support and equipment to upgrade its security.

- In June 2016, a police department in Collinsville, Alabama, refused to pay the ransom and lost access to a database of mugshots.

- The Cockrell Hill, Texas, police department was attacked in December 2016. The department thought that it could restore files; however, the files were not properly backed up and the department lost eight years' worth of digital evidence, including some documents, spreadsheets, video from body-worn and in-car cameras, photos, and surveillance video.

- In February 2017, the Roxana, Illinois, Police Department fell victim to a ransomware attack. Although the department refused to pay the ransom, the incident still cost the city considerable time and money. Rather than pay the ransom, the department was forced to "wipe the system." The department had backups of all important information, though restoring those backups in a usable manner is requiring significant manpower.

In a 2016 whitepaper on the topic of ransomware, the Osterman Research Corporation stated "both phishing and crypto ransomware are increasing at the rate of several hundred percent per quarter, a trend that it is believed will continue for at least the next 18 to 24 months." The report went on to point out the "FBI estimates that ransomware alone cost organizations $209 million in just the first three months of 2016."

According to former U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey, "Cybercrime is becoming everything in crime. Again, because people have connected their entire lives to the Internet, that's where those who want to steal money or hurt kids or defraud go."

Various foreign entities, such as China, Russia, and North Korea, are known to be engaged in hacking activities. But there are also literally millions of individuals who operate on their own by purchasing hacking tools on the dark Web.

According to the 2015 Trustwave Global Security Report, attackers receive an estimated 1,425 percent return on investment ($84,100 net revenue for each $5,900 investment in software and tools). Cybercrime is becoming easier and safer to commit thanks to the relative anonymity of the Internet and the availability of hacking tools for purchase, also referred to as "malware as a service" schemes.

This means that literally, anyone with a computer and Internet access can become a hacker, as programming and networking skills are no longer a requirement.

Legal Liability

The immediate damages caused by a breach are just the tip of the iceberg. A class-action lawsuit from residents whose credit card information was exposed through a local government's online fee payment system will hurt, but relatively few of them will have suffered direct, unreimbursed losses. Their losses were generally absorbed by their banks and insurance companies.

What do you tell the voters who's PII and PHI is exposed to identity thieves through the actions (or inaction) of their state or local government? How do you deal with the loss of public trust that accompanies this type of event?

As the holder of that confidential information, there comes a level of responsibility to take proper precautions to protect it. Breach that responsibility and there may be consequences.

Think of how the information your organization collects and processes could be used to commit a crime:

- PII could be used to commit identity theft.

- Personal information on children, witnesses, informants, victims of crimes, and other vulnerable populations could be used to violate their privacy or facilitate crimes against them.

- Information on regulated business could be used by business rivals.

- Information on government bidding, contracting, or economic development plans could be used to competitive advantage.

- Information dealing with active investigations (civil, criminal, or administrative) could be used to compromise those investigations.

Personal information on government employees could be used to exact revenge for unpopular decisions or actions.

Insurance Loopholes

A governmental insurance policy can provide protection; however, in the face of the extreme costs of a breach, insurance companies may find ways to decline coverage.

If the insurance policy doesn't specifically provide coverage for data breach-related damage, or if the insured agency fails to adhere to the details specified by the insurer pertaining to security measures, the insurer is likely to refuse payment.

Insurance companies may agree to cover a governmental entity for losses caused by cyberintrusions and data breaches, but there will be requirements that must be met by the insured. Where a claim is submitted, an investigation will ensue, and where security requirements have not been met, a claim will likely be denied.

In what appears to be a landmark case, Cottage Health System of California suffered a data breach in which 30,000 records containing PII were exposed in a cyber incident. A class action suit in 2014, filed on behalf of the affected clients, resulted in a $4.125 million award against the health system, in state court.

Although Cottage Health had a cyberinsurance policy with Columbia Casualty, the insurer pointed out that the insured stored the confidential information on an Internet accessible system, but failed to install encryption or other safeguards. The insurer denied the claim. Imagine if your locality were suddenly confronted with that kind of financial loss.

To effectively mitigate the dangers involved in data breach and cyberintrusion, it is important to understand as much as possible about these types of attacks. In an effort to better understand the impact these crimes are having on state, local, territorial, and tribal government, the National White Collar Crime Center (NW3C) has for several years assembled a data set of incidents using publicly available data from a wide range of sources.

Analyzing the Data

As of January 1, 2017, NW3C's data set of state and local governmental entities reporting data breaches totaled slightly more than 1,900 incidents. The organization's analysis of this information points to some important differences between the public and private sectors.

Recall that a data breach does not require a cyberintrusion; it can involve the exposure of confidential information through lost paper files, improperly disposed of electronic devices with digital memory, even intentional theft.

A cyberintrusion also may not necessarily involve a data breach. Technically hacktivism is where a hacker illegally accesses a computer network for the purpose of defacing or otherwise interfering with that network is a cyberintrusion but does not involve the breach of confidential PII and PHI.

When examined across all sectors, the data breaches resulting from cyberintrusions or hacking within the past 10 years account for less than 30 percent of the more than 5,000 data breaches reported by the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse. This includes not only the public sector but also retail, education, and health sectors.

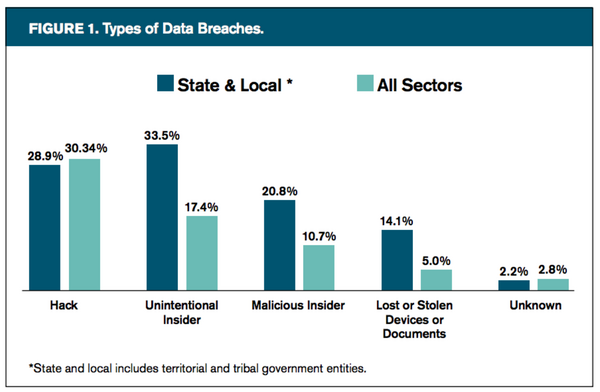

Analysis of the state/local-specific data that NW3C compiled showed the percentage of government cyber incidents involving hacking differs somewhat from that of the combined sectors of retail, education, healthcare, and nonprofits. What stands out most in our analysis is that insiders in government-related data breaches played a far greater role (see Figure 1).

Analysis of the cases in NW3C's dataset indicates the government sector shows a 48.05 percent greater propensity (difference between 17.4 percent and 33.5 percent) to suffer from unintentional insider breaches and a 48.55 percent greater propensity to suffer from malicious insider breaches, while the probability of suffering a data breach through lost or stolen devices is 64.53 percent less in the government sector.

The insider seems to play a noticeably greater role in data breaches in government than in the other sectors commonly tracked. Regardless of why public employees appear more prone to causing data breaches, the importance of our findings is that it facilitates identification of potential solutions that can potentially help reduce the incidents of data breach.

Reducing Risk

Due to space limitations and the extensive list of remedial actions available that could mitigate incidents of data breach and cyberintrusion, a comprehensive program is far too much to address in the space allotted for this article. We can, however, outline several basic steps, which can serve as the starting point for a comprehensive program that could reasonably be expected to result in reducing an agency's exposure to risk.

There is an array of technical tools that an IT coordinator can choose from to help ensure network security; however, in addition to those tools, a manager should consider the personnel-related aspects of security. Here are some basic steps.

- Establish detailed and thorough policies pertaining to Internet use. Encrypt e-mails and other content containing sensitive or confidential data. Enforce rules regarding access to personal social media accounts in the course of the workday. Direct the IT coordinator to be responsible for the monitoring of all communications for malware. Control the use of personally owned devices that are able to access corporate resources.

- Implement best practices for user behavior. Employees must select passwords that match the sensitivity and risk associated with their data assets. Employee passwords not only must meet certain criteria pertaining to strength, but also must be changed on a regular basis. IT departments should be required to keep software and operating systems up-to-date to minimize malware problems. Employees should receive thorough training about phishing and other security risks, and they should be tested periodically to determine if their anti-phishing training has been effective. Employees whose duties involve off-site Internet access, should be trained in best practices when connecting remotely, including the dangers of public Wi-Fi hotspots.

- Maintain a timely and complete backup of your critical systems.

- Regularly practice restoring your system from those backups. It is important to be aware that there are strains of ransomware that can be programmed to activate on a time delay, so backups may end up including the latent ransomware program. A careful manager needs to be aware that backups alone may not be effective unless they have been thoroughly checked and determined to be safe.

- The Intelligence National Security Alliance (INSA 2013) practice recommends that a risk-reduction program includes an insider threat component that encompasses, at a minimum:

- Organization-wide participation.

- Oversight of program compliance and effectiveness.

- Confidential reporting mechanisms and procedures to report insider events.

- An insider threat incident-response plan.

- Communication of insider threat events.

- Protection of employees' civil liberties and rights.

- Policies, procedures, and practices that support the insider threat program.

- Data collection and analysis techniques and practices.

- Insider threat training and awareness.

- Prevention, detection, and response infrastructure.

- Insider threat practices related to trusted business partners.

- Inside threat integration with enterprise risk management.

For more information on the question of legal liability and what you can do to limit your exposure to the threat of cybercrime, see the NW3C white paper Cyberintrusions and Data Breaches that can be found at http://www.nw3c.org/research.

Cybercrime Incident

Mille Lacs County, Minnesota, and staff member Mikki Jo Peterick were forced to jointly pay $1 million to people whose Minnesota driver's license records were impermissibly accessed by Peterick when she worked as a child support investigator for the Mille Lacs' Department of Family Services. No allegations were made of the use to which such information might have been put.

Settlement Agreement, Candace Gulsvig et al v. Mikki Jo Peteric et al., US District Court for the District of Minnesota, Civil File No. 13-cv-1309 (JRT/LIB) https://www.knowyourrights.com/SiebenCarey/media/News_PDF/Settlement-Agreement.pdf.

Gerald Cliff, Ph.D., is research director, National White Collar Crime Center, Fairmont, West Virginia (gcliff@nw3c.org).

Editor's Note: Results from ICMA's 2016 cybersecurity survey are available here.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!