Every local agency faces the essential dilemma of too many public needs chasing too few resources. Annual goal or priority setting1 with the governing body has long been considered a best practice in local government as a way to make decisions about which community priorities warrant an agency’s limited resources.

However, too often these efforts fail to deliver the hoped-for results. Priorities can be quickly forgotten, goals not achieved, new items can be thrown at staff during the year, and finger pointing and blaming can begin. When that happens, elected leader/staff relations suffer, and the priority- or goal-setting process itself becomes suspect. The local government’s public trust and legitimacy can even be weakened.

Goal setting often fails for one or more of these reasons:

- Unrealistic goals or too many goals.

- Lack of agreement on the process.

- Disconnect between the governing body’s goals and organizational capacity.

- Weak accountability for implementing the goals once set.

- Little measuring of results.

However, these common pitfalls can be avoided by exercising discipline and focus.

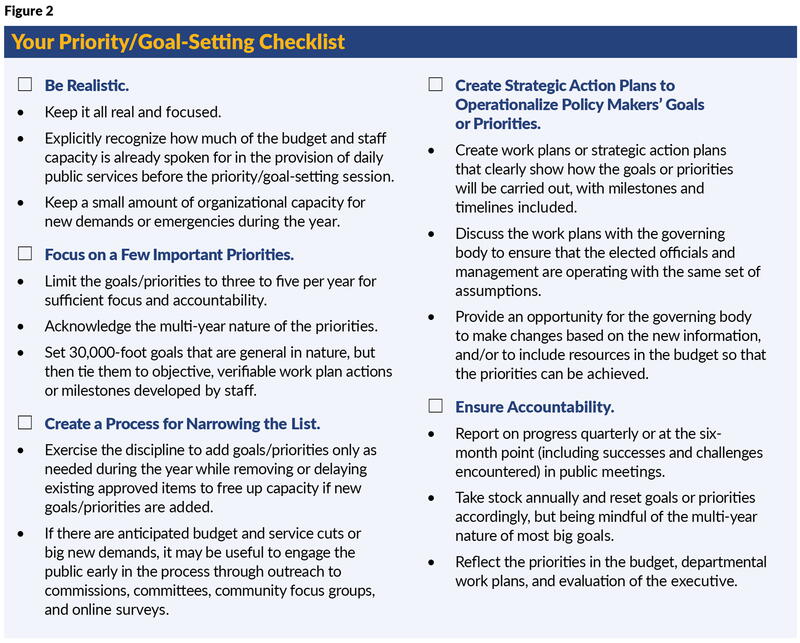

1. Be Realistic.

Too often local elected bodies set goals or priorities that are wildly outsized given the available budgetary and staff resources. Or they are set to be carried out in one year, when they are actually multi-year in nature.

Being realistic also means understanding the actual staffing and budget capacity available. It is understandable that elected leaders may assume there are more staff than there actually are available to deliver on the governing board’s project goals. Looking only at the full employee count and general fund budget, it can seem like there are a lot of people available to carry out the goals. But typically 90% or more are committed to core services and activities. Another small portion of organizational capacity is consumed by emergencies, new mandates, and emerging community needs that can’t wait. Thus, only a small remainder of staff time and public dollars can be applied to new goals and priorities each year. Sometimes, the choice is made to seek new revenue sources (such as new fees or taxes) to pay for important new priorities. Otherwise, funding and staffing capacity are inherently limited and must be considered in establishing priorities.

Being realistic also means establishing goals that can actually be achieved. At times, the language is so lofty that it would be impossible to achieve even if the entire budget and staff complement were devoted to them. Many things are outside the control of a local government, so in setting goals, it is important to know what is within an agency’s control.

Examples of unrealistic goals:

- Eliminating homelessness in the community.

- Providing housing for all who need it.

- Fully preparing for any emergency.

- Curbing emissions by 50%.

- Reducing single occupant vehicles on the road by 30% within a year.

Examples of more realistic goals for one to three years:

- Establishing a new outreach program to connect the unhoused population with social services. (Staff milestones could include a contract with a nonprofit organization; engaging a minimum of 20 unhoused individuals during the first year of implementation.)

- Providing zoning for new affordable housing units. (Staff milestones could include accommodating 250 new units for low-income families.)

- Increasing the community’s readiness to respond to disasters. (Staff milestones could include training all staff in emergency preparedness by the end of the first year; updating the emergency preparedness plan by the end of the second year of the two-year budget cycle.)

- Transitioning the fleet to electric. (A staff milestone could include transitioning 20% of the special district fleet to electric by the end of the two-year budget cycle.)

- Promoting the use of non-single occupancy vehicle transportation options in the community. (Staff milestones could include developing and implementing a marketing plan including incentives.)

2. Focus on a Few Important Priorities.

Even when the goals and priorities are in the realm of the doable, having too many also risks poor attainment. To be successful in reporting measurable attainment to the community, elected leaders should focus on a just a few (perhaps three to five) top goals for the year. What are their true priorities for extra attention by the organization’s management for the margin of capacity not consumed by daily services? This means prioritizing, compromising, delaying, or dropping some items.

Moreover, the priorities must be explicit and attainable. Otherwise, the governing body’s priorities can become a laundry list of campaign pledges and personal agendas. Staff simply cannot make progress on them all. Trying yet failing to adequately address a large number of priorities is demoralizing for staff, frustrates elected leaders, and disappoints community members, as well as undermines the agency’s credibility.

The priorities, while being explicit, should also be at the policy level. It is staff’s role to turn them into actions. When the governing body gets into the “how,” roles get confused. In seeking goals, it is best to stay at the high level with the policy makers, while seeking clarity about what they are expecting, and having a conversation about whether those expectations are reasonable and achievable.

3. Create a Process for Narrowing the List.

The process of winnowing down lists of goals or priorities to a handful must be carefully thought-out to avoid frustration. The Delphi technique in the form of dot voting is an easy method to reveal which items enjoy the most governing body support. The rules of engagement need to be stated up front so all know what to expect. For instance, no multiple dots by a single elected official on one goal item, and a majority of the governing body needs to show dots on any given item for it to end up as a “priority” for the year (or years).

Sometimes it is useful to have “tier 1” and “tier 2” goals, with the tier 1 being the 3-5 top items for staff and elected official focus for the year, and tier 2 being another 3-5 (at the most) to pursue as resources permit, but not to get in the way of the top-tier priorities.

Meaningful goal or priority setting necessitates discipline. It is all too common that the elected body adds new items throughout the year to the approved list. If that happens, then the priorities set at the outset can easily be pushed to the side, causing failures and frustrations.

Yet local governments are dynamic institutions and things happen during the year that may justify reshuffling the annual goals or priorities. It must be understood and mutually agreed upon by the elected body that items can be added to the priority list if it comes with delaying or dropping previously approved items to free up the staff capacity and resources for the new item(s). Recognizing that staff capacity is finite is critical. If something is added to the top of the pile, something must come off the bottom.

A good practice is to talk with the governing body about criteria they will use in deciding whether something new should be added to the staff’s plate. Or whether the “new idea” should just be put on a list for consideration at the next goal-setting session in a year or perhaps at a six-month check-in on status of the agreed-upon goals. If capacity exists to add something at that time, then it could be done.

The following are examples of criteria for deciding whether to add something to the list (and delay or delete something else):

- Is the new idea or initiative an emergency?

- Is there new outside funding that needs to be captured and timing is important?

- Is there a new multi-agency opportunity that is time-sensitive and critical to the local government?

Otherwise, discipline should be exercised to not add new items to the plate. When things are added without regard to the agreed-upon goals, it falls to the chief executive to make the call about what his or her staff will spend time on—essentially doing the prioritization himself or herself. Intentional and transparent policymaking by elected leaders, with advice from professional staff, is the hallmark of high-functioning public agencies.

4. Create Strategic Action Plans to Operationalize Policy Makers’ Goals or Priorities.

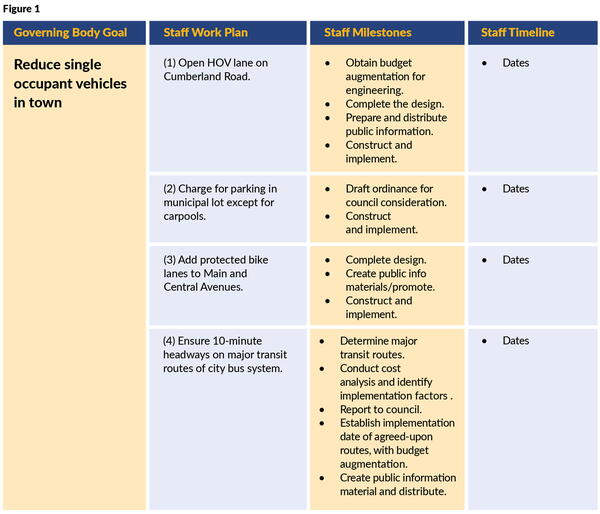

Effective public organizations turn the policy makers’ agreed-upon goals into strategic action plans. This is the staff’s role. After the elected body agrees upon a handful of goals or priorities for the year, the staff should return to the elected body (within a specific timeframe) with concrete actions or milestones to implement those goals or priorities. This constitutes the staff’s work plan to operationalize the priorities, and it’s how accountability for the priorities can be tracked.

These plans will then be synced with the budget, so when the governing body sees the budget, they will understand how their priorities are imbedded within it. Most of the goals that emerge from policy makers require more than one year to achieve, so by using this work plan or strategic action plan approach, staff can clearly show the timeline involved.

It is also how the staff and governing body can ensure they are on the same page with expectations, as well as with budgetary and other resources needed to achieve the priorities. Staff should also explain what these discrete actions entail and answer the elected leaders’ questions.

This may well involve discussion, negotiation, and adjustments of the work plan items until the elected body and management are in alignment as partners, which is critical for success. It is a chance for the elected leaders and senior staff to work as a team in their respective roles and areas of expertise: policy-making consistent with public needs married to effective and efficient implementation and administration.

The work plans then become the road maps that guide the departments beyond the rendering of day-to-day public services. See Figure 1 as an example.

5. Results Require Measurement and Accountability.

The fifth most common failure of local government goal or priority setting is failure to follow up, make course corrections, and ensure accountability. This is the chief executive’s responsibility.

Metrics are needed to ensure staff accountability and governing board oversight. Are milestones specific and tangible with timelines so it is clear whether they are achieved (or not)? Did the results occur as expected or are course corrections needed?

Priorities must be incorporated into the budget and work plans of the departments and city manager, county administrator, or general manager.

Elected leaders should receive quarterly reports at regularly scheduled public meetings on progress made and difficulties faced in meeting the goals or priorities. This includes the chance for discussion and for the elected leaders to give direction for adjustments and recalibration as needed.

The chief executive should be collaborating with department directors between the reports to keep things on track and adapt to changing circumstances, while keeping the council or board appraised of significant deviations. At year’s end, the staff should prepare and present a report on goal or priority attainment for public discussion at a governing body meeting. Goal attainment should figure prominently in the chief executive’s performance evaluation as well.

If the agency’s management system includes these steps, staff will be accountable and the council/board will be in the know and in its proper role of overseeing public agency progress toward agreed-upon goals/priorities. The process is then repeated and becomes the way things are done. The local government gets traction and gains trust and credibility.

Goal Setting for Success

Audit your goal- or priority-setting process with these practices in mind for greater effectiveness and service to your community or constituents. Getting things done requires focus, being realistic, regular communication, and staying on track. Elected officials, staff, and the public served all gain as a result.

Endnote

1 Although there are technical differences between goal setting and priority stetting, for the purposes of this article the terms will be used interchangeably. The common purpose is to focus time, attention, and resources on the matters of greatest importance to the elected leadership of the agency.

ROD GOULD, ICMA-CM is chairman of the board of HdL Companies, a former ICMA Executive Board member, retired city manager, consultant, and supporter of all those who toil in local government service. (rodgould17@gmail.com)

DR. FRANK BENEST, ICMA-CM (RETIRED) is a retired city manager and currently serves as a local government trainer and ICMA’s liaison for Next Generation Initiatives. He resides in Palo Alto, California. (frank@frankbenest.com).

JAN PERKINS, ICMA-CM is vice president of Raftelis, a local government management consultant and facilitator, retired city manager, and a believer in good government and in the city management profession. (jperkins@raftelis.com)

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!