I’ve recently been appointed to serve as a manager of a capital projects team in a large urban city. The group includes planners, engineers, and project managers. The team is technically competent and we have the necessary funding for the work plan. However, we have a backlog of projects and I sense little urgency and not much commitment to energetically address the backlog.

I’ve tried to take charge, energize the group, pick-up the pace, and instill some much needed accountability. The city needs to get some of our buildings and other infrastructure upgraded or replaced, as well as move forward on a few new parks and libraries.

The team doesn’t seem to be following my lead. I know that I’m a new manager, and I have some shortcomings, but I believe with some guidance I have what it takes to serve as a good leader. Do you have any suggestions?

I congratulate you on your appointment. I sense that you are committed, understand the importance of the team mission, and are energized by the leadership task, yet frustrated that your team members are not enthusiastically responding. Even though you have management authority, people are not following.

To succeed as a leader, you must understand a few key paradoxes of leadership.

What’s a Paradox?

A paradox is a seemingly contradictory proposition that when investigated proves to be well-founded or true. For instance, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Hamlet states that “I must be cruel in order to be kind.” Another paradoxical truth is that you cannot take care of others if you don’t take care of yourself.

The Five Paradoxes of Leadership

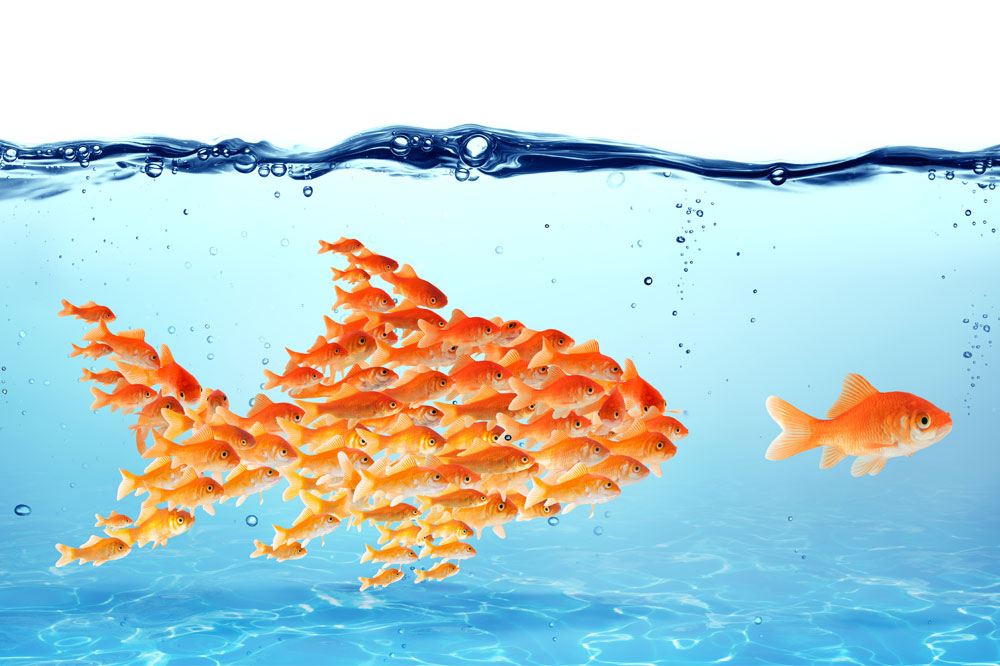

1. Followers make the leader

Leaders cannot force people to follow. Your formal authority as a manager can only force a minimal level of compliance. Followers choose to follow. So, here’s the big question: How do you create relationship and connection and exert influence so followers decide to follow?

The most important lever for leaders is engagement. Some key strategies for engaging employees (or coworkers) include:

Talk about the meaning and purpose behind the work

As Daniel Pink declared, “meaning is the new money.” You can start a conversation with team members about the importance of the new library or park, or better yet invite a few librarians and library users to attend a staff meeting and talk about the positive impact of the planned new library.

Engage team members in identifying its “collective ambition” and a few priorities and goals

A good starting point is to identify with team members what great things you all can do together (in other words, your “collective ambition”). You can also get their “fingerprints” on a few priorities and goals, which then become shared priorities and goals. Shared purpose, a “collective ambition” and a few common goals lead to accountability (see Career Compass No. 53: How Do I Hold People Accountable?).

Allow autonomy within certain “guide rails” or boundaries

Once you all establish some boundaries or “guiderails” (i.e., general direction, budget, timeline), the leader must allow team members to “figure it out.” Autonomy is a key driver of motivation.

Promote learning and growth

People want to be challenged, learn and grow, and in the process, master their craft. So debrief ongoing work with the group by asking:

What has gone well?

What has not gone so well?

What have we learned for future efforts?

You can also engage employees in stretch assignments where there is a 50-70% chance of success (this is the “sweet spot” of learning and development).

Show you care

Employees are engaged by leaders who show they care. You demonstrate that you care by engaging team members in conversations about their individual interests and hopes, as well as the team’s purpose and goals, and providing opportunities to learn and stretch and grow. You create connection by showing you care and thereby increase the opportunity to exert positive influence.

2. Great leaders go slow to go fast

To build some momentum and urgency about your agenda and priority capital projects, you need to take the time to. . .

- Get to know staff personally--who they are, what their interests are, what their strengths are, what a great day looks like.

- Involve the team in discussions of the big challenges, priorities, and goals.

- Engage internal stakeholders (your client departments) and external stakeholders (park and library users, business and neighborhood groups).

- Develop a work plan and project plans that has everyone’s fingerprints on them.

After going slow, you can accelerate and go fast.

3. Great leaders don’t motivate anyone

A leader cannot motivate others. A leader can identify the right people for the right project, help articulate the meaning or the “why” behind a project, and then help align the interests of team members and their strengths and ambitions with the project. It is then that people get energized if they have the autonomy to do great work together.

4. Only strong leaders show vulnerability

Followers will follow you as a leader if they form a connection with you. People tend to connect with those leaders who show vulnerability. Strong leaders exhibit vulnerability when they say:

- “I don’t know.”

- “I need your help.”

- “I made a mistake.”

- “I don’t know how to proceed. Can you help us figure it out?

(See Career Compass No. 32 The Power of Vulnerability.)

In our culture, vulnerability is often seen as a weakness. Weak leaders avoid showing vulnerability. Strong leaders can exhibit vulnerability and thus increase their leadership capabilities.

5. The more leaders seek control, the less control they have

The environment of local government is uncertain and constantly in flux. The military calls this kind of environment “VUCA” (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous). A leader can’t control a VUCA situation.

The waves of demographic, social, technological, economic, and political change are too big and cannot be resisted. You may point in what you think is the right direction, but followers can decide not to follow (even if you have management authority).

Instead of trying to control a world in flux, the leader must rather try to shape the change as it occurs. To do so, the leader must. . .

- Start conversations with employees and external stakeholders.

- Explore the emerging changes.

- Help people understand the meaning that compels us to act.

- Develop the collective ambition of the group.

- Agree to certain guiderails or boundaries.

- Let the team members figure it out and test out approaches.

- Provide support and help the team make adjustments.

In other words, leaders must “lead by letting go” (see Career Compass No. 46 Leading By Letting Go).

Bonus Paradox--Great leaders are flawed

All great leaders have been flawed. For instance, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Martin Luther King, and Steve Jobs were seriously flawed. Think of a leader whom you have chosen to follow—you have probably observed some weakness or flaw.

Great leaders minimize their flaws by doing several things. First, they are self-reflective and self-critical. By understanding their life stories, they recognize the “gifts” that they are compelled to give away and their shortcomings, which must be minimized if they are to succeed. For instance,, given my life history, I have become a great ideas guy. That’s my gift. However, being self-critical, I acknowledge that when I step into a team meeting to share my exciting ideas, I suck all the air out of the room. Others don’t share their ideas and simply acquiesce. Whatever plan that is developed is only owned by me. The team minimally complies with the plan because it is not their plan.

Second, being self-aware, flawed leaders modify their behavior. So, in team meetings, I’ve learned to first ask others for their ideas and then incorporate my ideas as the discussion occurs.

Third, many great leaders minimize their weaknesses by surrounding themselves with team members or other partners who exhibit strengths in areas where the leader has a shortcoming.

To lead, we leaders must believe that we are worthy to be followed even though we are flawed (Brene Brown, TED.com talk, “The Power of Vulnerability”).

An Opposable Mind

To understand and be guided by these paradoxes of leadership, you need to develop an “opposable mind.” (See Roger Miller’s book An Opposable Mind—How Successful Leaders Win Through Integrative Thinking.) An opposable mind allows you to hold two opposing yet true thoughts at the same time. For example, I need to go slow to go fast. I need to motivate by not trying to motivate. I show strength by showing weakness.

Good luck incorporating these paradoxes into your daily leadership practice.

Other Paradoxes of Leadership?

Readers, do have some other paradoxes of leadership? Let me know at frank@frankbenest.com. Thanks for sharing.

Sponsored by the ICMA Coaching Program, Career Compass is a monthly column from ICMA focused on career issues for local government professional staff. Dr. Frank Benest is ICMA's liaison for Next Generation Initiatives and resides in Palo Alto, California. If you have a career question you would like addressed in a future Career Compass, e-mail careers@icma.org or contact Frank directly at frank@frankbenest.com. Read past columns at icma.org/careercompass.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!