ICMA's Local Government Program Excellence Awards outstanding local government programs.

PROGRAM EXCELLENCE AWARDS

-

Community Diversity & Inclusion

-

Community Partnership

-

Community Health & Safety

-

Community Sustainability

-

Strategic Leadership & Governance

Community Diversity & Inclusion

Under 10,000

CONNECTING OUR COMMUNITY TO BE MORE INCLUSIVE

Flossmoor, Illinois

|

|

|

| Bridget Wachtel, Village Manager | Allison Deitch, Assistant Village Manager | |

Flossmoor, Illinois, has a picture-perfect, small-town America look and feel; however, its 9,400 residents are a microcosm of the larger world in their diversity. The village is one of the few local governments in the Chicago area to resist the segregation that has plagued the region.

The village decided to do something about it. During 2016, Flossmoor had reinvigorated its resident-led community relations commission. The commission launched its first community program in 2017, Martin Luther King, Jr., Day of Service (“Make it a Day ON”), which is now one of its signature events. For the first time, local nonprofits joined the village in hosting service projects. In 2018, the event became larger, drawing more than 700 volunteers of all ages.

The village and the commission have staged other low-cost programs and events to make it easy for residents to connect with each other and with staff members. Village Manager Wachtel and staff have made it a multiagency effort by involving the local school and park districts.

A regularly scheduled movie in the park event added a back-to-school celebration so residents could meet school administrators. And on the first day of school, the commission invited residents to “Chalk the Walk,” which involved writing inspiring messages on the paths to local schools. Local Parent Teacher Associations and the police department have joined in with the events.

The commission also resurrected its new-resident get-together, where more than 40 recent arrivals had the opportunity to meet staff, village board members, and each other.

Flossmoor has deliberately chosen to emphasize its diversity in its communications. During its branding process, staff used photos of community residents and families as much as possible rather than stock photography. Flossmoor also became the first south suburban community to list LGBTQ resources on its website.

Finally, throughout Black History Month, the village’s social media platforms featured short profiles of African Americans living in Flossmoor or who have connections to the community.

Flossmoor has found that even if a community has a small budget, it can make living there more inclusive with a little effort, energized staff, and motivated volunteers.

10,000 to 49,999 Population

YOU, ME, WE = OAKLEY!

Oakley, California

|

|

|

| Bryan Hyrum Montgomery, ICMA-CM, City Manager | Nancy Marquez, Assistant to the City Manager | |

Since 2008, Oakley, California, has had one of the fastest growing immigrant populations in California. Nearly 40 percent of Oakley’s population is Hispanic, with an even higher percentage among students.

City leaders recognized the need to build trust between recent immigrants and long-term residents, which led them to Welcoming America, a national grass-roots collaborative that promotes cooperation and communication between immigrants and U.S.-born Americans (https://www.welcomingamerica.org). They formed a project committee and established You, Me, We = Oakley! (YMWO) as a Welcoming America affiliate.

YMWO’s project committee includes City Manager Bryan Hyrum Montgomery; Assistant to the City Manager Nancy Marquez; two city councilmembers; school leaders; nonprofit organizations; faith-based leaders; students; and resident volunteers. A paid part-time coordinator helps guide the program.

YMWO’s project committee, staff, and volunteers have created a rich, multifaceted program combining communications, public engagement, and local leadership activities. Program activities all share the goal of helping U.S.-born and immigrant residents better understand one another, appreciate each other’s stories, and recognize their common desire to build a stronger, safer, more vibrant community.

Here is a sampling of program offerings:

- Video telling the stories of immigrants who live in and love Oakley.

- Help for residents who want to research their family history on Ancestry.com.

- Potluck dinners featuring foods from residents’ countries of origin, where attendees discuss their common community concerns.

- Citizenship drives that have helped more than 100 residents become U.S. citizens.

- Volunteer program for residents who assist at events and help monitor social media for hateful or racist comments or language.

- Mental health seminars where people of all faith and ethnic backgrounds discuss community mental health concerns.

- Public safety outreach and neighborhood watch meetings in Spanish.

- School outreach to parents and events to teach students that hate, bigotry, and bullying can be replaced with kindness and respect.

- “Know Your Rights” workshops.

- Citizen leadership academy presented in Spanish, one of the more effective efforts to encourage civic participation by recent immigrants.

- Training to raise city employees’ awareness of their own implicit biases.

- Translation of city documents into Spanish and creation of how-to documents to assist recent immigrants in their interactions with the city.

While YMWO is part of the Oakley city organization and team, the program is grant funded. More than $500,000 in grant funds have been received to date.

50,000 and Greater Population

EQUITY INITIATIVE

San Antonio, Texas

|

| Sheryl Sculley, City Manager |

Eight years ago, thousands of San Antonio, Texas, residents helped write a vision statement laying out their collective hopes for their diverse, vibrant city. The city’s Office of Equity has the responsibility for continuing the coordination efforts to achieve the vision within the city organization and with community partners.

Its work is driven by acknowledging the crucial role city services play in the prosperity of San Antonio residents, committing to fostering a mission-driven culture, and understanding the importance of earning the community’s trust through responsiveness and accountability.

- Who in the community is most affected by or has experience related to a proposed initiative?

- Are they involved in the development of the initiative?

- What factors produce or perpetuate inequity related to the initiative?

- How will the city continue to deepen relationships with communities to ensure their work to advance equity is effective and sustainable?

San Antonio’s Government and Public Affairs Department (GPA) leads “SA Speak Up,” the largest annual initiative to gather community input on the city’s $2.7 billion budget.

GPA demographic data in 2016 and 2017 found that respondents did not reflect the population by race, gender, age, or council district. Engagement was lowest in communities of color and low-income communities, as well as among young people.

In 2017, GPA conducted the equity impact assessment and consequently adjusted its outreach strategies. Instead of leading a traditional town hall meeting, GPA hosted the first Spanish-language community night in a district with the highest density of Latinos. It drew 200 people, the highest turnout ever for a SA Speak Up event.

This year, the Government Alliance on Race and Equity and SA2020, a local nonprofit, trained 100 city employees to apply an equity impact assessment to seven high-impact initiatives, including SA Speak Up.

As a result, its strategies for gathering input on the 2018 budget include mailing postage-paid surveys in English and Spanish so community members without access to the Internet can participate and administering surveys at grocery stores in target council districts and historically under-engaged areas. The budget for the 2018 equity strategy is $210,907.

From this visionary project, San Antonio has learned that community engagement strategies should be developed in partnership with historically under-engaged populations, and that data should be collected and analyzed, disaggregated by race, gender, age, and council district.

Community Partnership

Under 10,000 Population

IRV AND MARY SATHER SKYLARK SKATE PARK

New Richmond, Wisconsin

|

|

|

| Mike Darrow, City Administrator | Noah Wiedenfeld, Management Analyst | |

Young people in New Richmond had wanted a quality skateboard and BMX (bicycle motocross) facility for more than a decade but residents’ concerns about noise, safety, and crime stalled the project.

In 2015, longtime residents Irv and Mary Sather pledged $40,000 to jump-start construction. The New Richmond Park Board voted to designate a site of some 7,500 square feet for the new facility at an existing sports complex. A resident-led group then researched skate park designs, prepared cost estimates, and identified funding sources.

hen, when the first two public meetings attracted a sparse turnout and the proposed design came in at more than $200,000, the project appeared to have stalled.

Rather than let the park die, City Administrator Mike Darrow took it on, designating two staff members to work on the project. They visited skate parks in the region, consulted other public works departments for advice, and researched design-and-build companies, coordinating throughout with the resident group and park board. The most likely users of the park—young people—had their say during meetings city staff convened during and after school.

In early 2016, the city won a $10,000 grant from the Tony Hawk Foundation. The residents group took over fundraising, soliciting donations, and in-kind contributions from more than 50 local businesses. City staff helped manage the funds and handled the request for proposal process for a company to design and build the park.

Construction began in July 2017. When the park opened in September 2017, it was an instant hit with local adults and youth alike.

Other than in-kind labor and the land, the project used no taxpayer dollars. More than $132,000 was raised, and such amenities as landscaping, a bicycle air pump and repair station, and benches were donated later. Today, the skate park attracts users from a 100-mile radius. Despite early concerns, there has been no crime or rowdy behavior.

The city learned these two important lessons: Involving young people would require going to the kids rather than vice versa, and the role of local government in fundraising must be clearly delineated to ensure that the public trust is never jeopardized.

For their part, residents learned that if even just a few people take initiative, they can create positive change in their community.

10,000 to 49,999 Population

GLASTONBURY RIVERFRONT PARK AND BOATHOUSE

Glastonbury, Connecticut

|

|

|

| Richard Johnson, Town Manager | Ray Purtell, Director of Parks and Recreation | |

Located southeast of Hartford, Connecticut’s capital, Glastonbury had nine miles of shoreline on the Connecticut River but no public river access for boating or recreation.

Town and state plans had documented the need for improved public access to the river for more than 30 years. Here is the list of additional needs:

- Access for water-based recreation.

- Community center.

- Meeting and banquet facilities.

- Athletic facilities.

- Fairgrounds.

- Dog park.

- Trails and sidewalks.

- Facility for emergency access by town first responders.

efore work could start, the town had to remediate 23 riverfront acres, the site of a long-abandoned oil storage and distribution facility. Then, construction proceeded in stages. Strategic partnerships were key throughout for fundraising, input, and rallying public support.

1999 to 2009: Glastonbury acquires seven parcels of land to create 126 contiguous acres with river frontage. Cost: $2.3 million.

The town develops a cleanup plan with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP).

2001: Voters approve a $1.2 million bond authorization for the cleanup; EPA and DEEP provide an additional $600,000. Completed in 2004.

2002: Glastonbury relocates a road to form a contiguous open space for the community center and fairgrounds. A $5.9 million bond authorization and a $750,000 state grant fund construction of the 20,000-square-foot center, which opens in 2005.

2006: Voters approve a $4.25 million bond authorization for Phase 1 of the park, which includes athletic fields, picnic pavilion, parking, and multiuse trails.

Fall 2007: The park opens. Volunteers and an excavation company fund and construct a two-acre dog park, which was completed in 2011.

2009: Glastonbury acquires land to link the community center and fairgrounds with Phase 1 area of the park.

2012: Voters approve a $12 million bond authorization for Phase 2, which includes boat launches for public and emergency river access; boathouse; banquet facility; basketball court; handicapped accessible playground; trails and river walk; and ice skating rink. Phase 2 completed in 2016.

Among the tools now in place, these lessons were a part of the learning process:

- Gain public input through multiple channels—focus groups, public forums, and small-group sessions—and use it to update plans promptly.

- Involve local, state, and federal permitting agencies early.

- Clearly define tangible benefits for individual partners.

- Develop the project in stages to allow the public to experience the benefits while subsequent stages of work are in process.

50,000 and Greater Population

TALLAHASSEE FUTURE LEADERS ACADEMY

Tallahassee, Florida

|

|

|

| Reese Goad, Interim City Manager | Angela Hendrieth, Manager of Workforce Development | |

|

||

| Willie Williams, Talent Development Specialist II/TFLA Program Coordinator | ||

The Tallahassee Future Leaders Academy (TFLA) has been described by the National League of Cities (NLC) as “…a shining example of diversity and total community collaboration and partnership.” TFLA received NLC’s City Cultural Diversity Award this year.

TFLA grew out of Tallahassee’s summer youth program in 2014 when Mayor Andrew Gillum saw there was an urgent need for something more structured that would prepare young people to enter the workforce.

It recruits from throughout the city but prioritizes youth who live in an area called the Promise Zone, where the poverty rate is 52 percent and the overall unemployment rate is a little more than 20 percent, three times the city average.

TFLA runs for eight weeks. Its curriculum has these five components:

- Job readiness training (two weeks). In addition to learning skills necessary for success in the workplace, participants can gain professional certifications in safety training, customer service and sales, and safe food handling.

- Employment (six weeks). Participants work at least 20 hours per week in paid positions with the city or local businesses, and are mentored by their managers or supervisors.

- College exposure. Florida A&M University, Florida State University, and Tallahassee Community College offer campus tours and an introduction to college life.

- Financial literacy and education. A local credit union teaches the basics of establishing and maintaining good credit, budgeting, and setting financial goals.

- Community impact. Participants can take part in city-organized community service activities and events.

Despite minimal access to resources in the past, the program has increased the number of participants and business and community partners each year. Some $46,000 of its revenue comes through sponsorships and donations from community partners and grants.

Now going into its fourth year of operation, more than 600 youth have participated in the program, which has a 94 percent completion rate. Participants also have received a total of 1,058 professional certifications, and 58 percent of the participants plan to attend a four-year university; 33 percent want to attend community college.

Even though the city is at the forefront of job training, it also has learned these lessons about its academy:

- Extending TFLA to a full year and increasing program options would magnify its impact.

- TFLA needs full-time staff to manage and evaluate the program and recruit more businesses to employ participants.

- Since most participants are students from the Leon County Schools (LCS), collaboration between TFLA and LCS will be critical to increase their chances of success.

Community Health & Safety

Under 10,000 Population

ACTIVE SHOOTER TRAINING

New Richmond, Wisconsin

|

|

|

| Mike Darrow, City Administrator | Craig Yehlik, Chief of Police | |

During the past decade, mass shootings have become a tragic fact of life in the United States. No community, regardless of size, is immune. New Richmond, Wisconsin, decided to take a whole community approach to preparing for a disastrous event.

The city’s police department is among the first public agencies to require all of its officers to complete certification in advanced law enforcement rapid response training. ALERRT, which has been used by the FBI to train its agents since 2013, is considered the national standard and the best research-based training of its kind.

The police department has also worked closely with the city’s school district to prepare a response plan using a procedure called ALICE (alert, lockdown, inform, counter, and evacuate). All school personnel received ALICE training in 2015; students participated in age-appropriate curriculum and drills in 2016.

What have been the tangible results? More than 250 residents have completed CRASE training. Plus, the positive relationship among the school district, police department, business community, and other organizations has inspired a year-long speaker series that will focus on such other topics as coping skills, substance abuse, suicide, bullying, and mental health.

While New Richmond’s police department has led the program, it came together because of support from City Administrator Darrow and the city’s elected officials, as well as the school district, technical college, parents, local businesses, private citizens, and others.

Local government managers may not be the public face of a program but behind the scenes, they still play a critical role in providing oversight and clear, consistent communication. Darrow and Yehlik have a close working relationship; as a result, New Richmond’s leadership takes a unified approach to public safety.

As New Richmond continues to focus on community health and safety for its residents, it has come to understand that active shooter training, for which there is high demand, enables law enforcement agencies to strengthen their community relationships while providing a valuable service. Along with this, plans that the city has in place to respond to an active shooter have increased residents’ appreciation for their law enforcement agencies. Everyone recognizes that a holistic approach to public safety requires the cooperation and participation of everyone in the community.

10,000 to 49,999 Population

A WAY OUT PROGRAM: LAKE COUNTY OPIOID INITIATIVE

Mundelein, Illinois

|

|

|

| John Lobaito, Village Administrator | Eric Guenther, Chief of Police | |

As the opioid epidemic has grown, so, too, has recognition that substance abuse is a public health problem that needs to be addressed as such. “A Way Out,” a program created by the Lake County Opioid Initiative (LCOI), aims to increase access to treatment, reduce crime, reframe the role law enforcement plays in public safety, and involve the community.

Between 2013 and 2016, Lake County experienced a 51 percent increase in deaths by any opioid, a 52 percent increase in deaths by heroin, and a 94 percent increase in deaths by opioid analgesics. A 2016 survey of Illinois police chiefs and county sheriffs suggested that local and county law enforcement collaborate with public health agencies to combine traditional policing with approaches that address substance abuse.

Unfortunately, Lake County has a shortage of treatment options, particularly for inpatient substance abuse treatment. All community providers that serve low-income clients have waitlists. A Way Out began as a pilot program in 2016 and has expanded in phases. Under the program, no criminal charges will be brought against anyone in possession of narcotics or paraphernalia if a person seeks help. This help is available 24 hours a day at 11 participating police departments across Lake County.

A Way Out has applied for grants to hire on-call coordinators to find immediate openings among participating treatment providers and coordinate with police to transport clients. The initiative also has applied for funds to create a patient assistance fund to pay out-of-pocket costs not covered by insurance or Medicaid.

Tangible results of the program show that since its inception, the program has had 321 participants, and local police departments are supporting the program. In December 2017, LCOI received $52,500 in donations from A Way Out’s participating police departments.

LCOI is working with Rosalind Franklin University to evaluate the program, including the number of participants, attitudinal shifts, treatment success, and clients’ ongoing interactions with the criminal justice system.

In assessing this program, staff members found:

- A program that lacks a dedicated funding source must engage in strategic planning early in the process to assess resources, goals, and potential challenges.

- Volunteer-run programs must have realistic expectations for what they can accomplish.

- Escalation of the opioid epidemic offers local government managers the chance to lead their communities in rethinking traditional approaches to addiction.

- Collaborative programs allow managers to showcase their skills as facilitators and conveners.

50,000 and Greater

DOUGLAS COUNTY MENTAL HEALTH INITIATIVE

Douglas County, Colorado

|

|

|

| Douglas DeBord, ICMA-CM, County Manager | Barbara Jean Drake, Deputy County Manager | |

Douglas County, Colorado, acts as a convener and facilitator, bringing residents together to confront critical issues that affect the community at large.

In 2014, the county’s board of commissioners gave Deputy County Manager Barbara Drake approval to form the Douglas County Mental Health Initiative. DCMHI had a mandate to assess the county’s mental health system, identify gaps, and develop collaborative solutions. Its goal: to keep people with mental health issues from falling through the cracks and posing a danger to themselves and the community.

DCMHI has 37 community partners, including law enforcement, fire and emergency medical services, human services, public and private health care, schools, faith-based organizations, mental health providers, and residents. It has two staff members—a coordinator and a program analytics specialist to collect data and track outcomes.

DCMHI’s Community Response Team (CRT) streamlines access to care for individuals who are caught in the proverbial “revolving door.” A mental health clinician and specially trained law enforcement officer patrol 40 hours per week, on a shift determined by highest volume of mental health-related calls. After the team triages the patient, the clinician can make an immediate referral to any level of treatment or place the individual directly into inpatient treatment. The team uses a special medical clearance that treatment providers accept in lieu of an emergency room visit.

CRT also makes follow-up visits and conducts preventative visits to individuals who have been identified as high users of emergency systems. Its case management team can coordinate ongoing care.

CRT started with a four-month pilot in 2017 within a limited geographic area. After the pilot proved successful, the project expanded to include unincorporated Douglas County, where the bulk of its population resides. The program now has two full-time teams and two full-time case managers.

Expenses for this initiative mostly consist of staff salaries and benefits, and the total program cost is $555,668 annually.

CRT handled 636 total contacts through mid-February 2018 with these results:

- 261 were responses to active 911 calls; 275 were follow-up contacts.

- 102 of the contacts diverted people from emergency rooms, 45 from jail.

- 52 percent of the individuals were treated in place.

- 65 individuals were placed directly into inpatient psychiatric care; the remaining individuals were referred to appropriate levels of care.

Also, thanks to CRT, there were 375 patrol officers, 107 fire employees, and 58 fire vehicles released back into service. Actual hospital savings for four high users alone is estimated at $300,000; not deploying fire services saved $52,000.

Community Sustainability

Under 10,000 Population

KENILWORTH 2023 INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENT PLAN

Kenilworth, Illinois

|

| Patrick Brennan, ICMA-CM, Village Manager |

Flooding had always plagued the village of Kenilworth, Illinois, since its founding in 1890. It wasn’t until 2009, however, after heavy rainstorms caused widespread flooding, that residents called for action. The village board initiated engineering studies and designs and, in 2011, concluded that the only solution was a separated storm sewer system that emptied into Lake Michigan.

The board then commissioned a capital infrastructure improvement plan, preliminary design, and budget and announced the Kenilworth 2023 Infrastructure Improvement Program (KW2023). It called for a $24 million, 10-year, three-phase project.

Village residents approved a referendum to grant the issuance of capital improvement bonds to fund the project. As plans were being developed, however, the village learned that the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency was unlikely to allow a new storm water discharge into the lake.

Village Manager Patrick Brennan researched options. Working closely with engineering specialists, he devised a plan that combined three green infrastructure technologies—bioswales, porous roadways, and underground storm water detention—into one approach called Green Streets.

The village used its regular communication channels to inform residents about the project, but received little feedback. Then, just before going to bid with the first design, a group of residents announced at a village board meeting that they didn’t want porous pavers.

The result: A one-year delay as the village considered design alternatives. The redesign used porous asphalt in lieu of pavers to receive the storm water.

The $5.9 million project finally broke ground in March 2016. The local sanitary sewer district provided $1.2 million in funding support for the unique project.

Phase I involved just three streets but had a communitywide impact. Brennan became the public face of the project. He appeared at meetings, responded to resident complaints, made site visits, and even carried the luggage of one resident who was going on vacation when construction blocked his street.

Phase I wrapped up in November 2016, and the new system performed flawlessly. Today, instead of flooding, the village’s challenge is responding to residents who want their street to be first on the list for Phase II.

As a result of this project, the manager and village staff learned these key lessons:

- If staff members are not hearing from residents about a new project, the community may not be reaching its intended audience.

- Consider a variety of approaches, especially if trying something new, and keep both current and past elected officials informed on the decision-making process.

- If an approach isn’t working, don’t be afraid to ask for help and change the original plans.

- Publicize successful results of a project as much as the process is publicized.

10,000 to 49,000 Population

CEDAR HILL GROWING GREEN PROGRAM

Cedar Hill, Texas

|

|

|

| Gregory Porter, ICMA-CM, City Manager | Melissa Valadez-Cummings, Assistant City Manager | |

Cedar Hill, Texas, is a thriving suburb located in the heart of the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex in an area known as the Hill Country. The city is an up-and-coming ecotourism destination thanks to its lush, tree-lined rolling hills and wide-open green space.

As the Metroplex grows, so does Cedar Hill, experiencing a 64 percent increase in its population since 2000. To protect its natural beauty, unique ecosystem, and open spaces for generations to come, Cedar Hill leaders created the Growing Green program.

The program has three goals: to build in-house expertise in sustainability, to optimize government’s energy use and reduce emissions, and to plan for the long term. It has guided elected and appointed city leaders in incorporating environmentally conscious practices into their strategic planning and operations.

In 2003, Cedar Hill’s leaders established a public-private partnership that preserved the Blackland Prairie ecosystem, home to more than 14 endangered species of birds.

In 2011, adding to a growing list of accomplishments, the city council adopted its first five-year sustainability action plan to promote renewable energy, public transportation, open space, water conservation, and solid waste and recycling services.

That same year, the city used $1 million in funding from the Department of Energy and Oncor to install a solar photovoltaic system on the roof of its government center. The system generates 210,030 kilowatt hours of electricity annually, for savings of more than $21,000.

Later that year, the city used a $50,000 State Energy Conservation Office grant to add wind power, with the installation of a turbine.

In 2012, the city and its partner Waste Management replaced every single-family home’s 19-gallon recycling bin with a 96-gallon cart and reduced trash collection to weekly. Recycling increased by 258 percent the first quarter; since the program’s inception, nearly 20,000 tons of residential recycling materials have been diverted from landfill.

Also in 2012, the city council adopted a master plan to preserve 20 percent of the city’s landmass as open space, more than double the national average for the most populous cities.

Most recently, Cedar Hill used a $300,000 grant from the Bureau of Reclamation to replace all water meters with automatic readers, eliminating meter-reading routes.

Staff have learned three lessons from the Growing Green Program:

- The big vision must guide planning and implementation.

- Achieving public buy-in for environmental sustainability must be a priority.

- Publicize successes and show residents how small changes can have a big impact.

50,000 and Greater

GREEN STORMWATER INFRASTRUCTURE AND LOW-IMPACT DEVELOPMENT

Raleigh, North Carolina

|

| Ruffin Hall, City Manager |

Raleigh, North Carolina’s capital city, has made it a priority to protect and enhance its quality of life in the face of rapid growth. Its Green Stormwater Infrastructure and Low-Impact Development (GSI/LID) program is one example of how the city puts its commitment into action.

The GSI/LID initiative grew out of strong interest from the community, city management, staff, and elected officials in reducing the negative effects of land development on surface water quality and the health of Raleigh’s streams and lakes.

From late 2013 through 2014, the city convened staff, members of council-appointed resident boards and commissions, development organizations, environmental and conservation organizations, and resident advocacy groups to develop a GSI/LID workplan. Consultant Tetra Tech, Inc., served as facilitator. The city council endorsed the plan in March 2015.

Next, City Manager Ruffin Hall and staff set up two work groups, both of which included city staff and external community stakeholders, to tackle specific tasks. They completed their work in March 2016.

The process of integrating GSI/LID into routine practices for land developers and designers, along with those who maintain Raleigh’s urban infrastructure, has three phrases; Raleigh was in Phase 3 when this article was written.

- Scoping to evaluate barriers, needs, and opportunities and to develop a strategic workplan.

- Building capacity within the city for long-term administration and implementation.

- Developing new policies, procedures, and tools to make GSI/LID a part of routine daily operations.

Under the GSI/LID aegis, the Sandy Forks Road Widening Capital Improvement Project replaced more than a mile of failing two-lane roadway; installed bioretention systems to treat stormwater runoff; and added a vegetated median, center turn lanes, bike lanes, and sidewalks, earning a Greenroads’ silver certification.

Raleigh’s Stormwater Management Program, which is housed within the Engineering Services Department, manages the program. Program development and early implementation costs are approximately $750,000 over five years, which has been funded by the city’s stormwater utility.

To be successful, the city found that innovative initiatives require:

- Aligned vision and support from top management and elected officials.

- Champions at all levels of the organization.

- Dedicated resources.

- Involved and engaged community stakeholders, particularly builders and land developers.

- Pilot demonstration projects to help lead the way.

Strategic Leadership & Governance

10,000 to 49,000 Population

LOCAL ECONOMIC REVITALIZATION TAX ASSISTANCE

Norristown, Pennsylvania

|

|

|

| Crandall Jones, ICMA-CM, Municipal Administrator | Brandon Ford, Assistant to the Administrator | |

|

||

| Jayne Musonye, Director, Planning and Municipal Development | ||

With a population of 34,412, Norristown, Pennsylvania, is considered a culturally diverse community in the Greater Philadelphia area. The local government promotes innovation and collaboration as critical components of its organizational culture and strategic planning.

Norristown’s Local Economic Revitalization Tax Assistance (LERTA) program epitomizes how the city puts innovation and collaboration into action. Since 2015, the LERTA program has used gradualist tax abatement schedules to encourage owner-driven revitalization and new construction.

Developers that qualify for LERTA still pay property taxes, although they pay only a portion of the additional taxes that are likely to result from the increased property value. In this way, LERTA allows developers and owners to recoup their investment in property improvements, supports job creation, and encourages future investment in renovations and developments.

The program also promotes public-private partnerships with companies and individuals, as well as intergovernmental cooperation with other local taxing entities, the county government, and the local school district. Staff from all three agencies meet regularly to discuss LERTA projects.

LERTA is a win-win for all three agencies since their only significant cost is time to administer the program. In fact, they’ve seen a gradual increase in property taxes based on the abatement schedule. Two developments in particular—the Five Saints Distillery and the Luxor Lifestyle Apartment Complex—openly attributed their decision to locate in Norristown to the appeal of LERTA.

Located on main street, the award-winning Five Saints Distillery is housed in a rehabbed fire station. With a bar that opens out onto the street, Five Saints has become a prime destination for those who live and work in town. The micro-distillery is now going through the LERTA application process to create a restaurant and event space on its upper floors.

The Luxor Luxury Apartments, a residential development that caters to Norristown’s growing young adult population, leased more than 90 percent of its units in its first few months. The developers have now acquired the neighboring property to build their second residential project in only three years.

50,000 and Greater

OLATHE PERFORMS

Olathe, Kansas

|

|

|

| Michael Wilkes, City Manager | Susan Sherman, ICMA-CM, Assistant City Manager | |

|

|

|

| Dianna Wright, ICMA-CM, Director of Resource Management | Edward Foley II, Performance Analyst | |

Olathe, Kansas, conducted its first resident satisfaction survey in 2000. At the time, the city issued annual performance reports in a PDF document. As city staff surveyed the performance management landscape, however, they took note of the emerging trend that communities were reporting more frequently using an interactive dashboard.

Research, resident and staff interviews, and discussions with the city’s performance management software provider ClearPoint Strategies, eventually led to the launch of a dashboard named “Olathe Performs” in 2017.

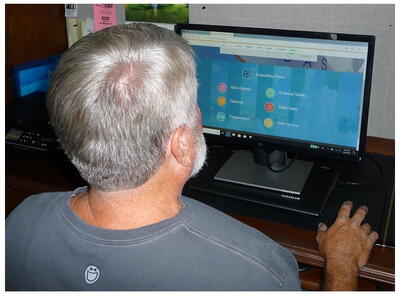

Olathe Performs is the city’s first public-facing performance management dashboard for residents. It is designed to increase resident engagement, data transparency, government accountability, and ease of information sharing.

Much of the up-front work consisted of research. City staff members did extensive reviews of 16 other cities’ public-facing dashboards, created a matrix of their findings, and developed a list of pros and cons for each. Meetings among key internal stakeholders, including City Manager Michael Wilkes, department directors, and Olathe’s performance management user group, fleshed out the full picture of Olathe’s needs. The city solicited input from residents throughout the process, analyzing the resulting data to determine the most relevant measures that were desired.

Finally, the city presented a mock-up of the dashboard to participants in its citizen academy for their suggestions. The costs totaled $10,000.

- A total of 1,923 sessions with 8,707 total page views.

- An average session duration of two minutes.

- Council key metrics, public safety, and active lifestyle were the most popular pages.

Tangible results include:

- The city updates the dashboard quarterly and has seen a solid, stable number of visitors during the past year.

- Front-line staff is more aware of progress toward organizational targets.

- Media coverage of the dashboard has increased positive awareness of the city, plus the dashboard will be the subject of a case study presentation at a 2018 Transforming Local Government conference.

The community has learned these lessons about establishing a dashboard:

- Create strategic partnerships.

- Take advantage of existing online platforms.

- Ensure the dashboard is consistent with organizational branding.

- Focus on your community’s primary audience.

Olathe staff stresses that any local government can create a community dashboard that makes data and other information readily accessible. With an easy-to-navigate structure and attractive presentation, a dashboard can help tell a powerful story.