By Norman Wright

A retreat can be a powerful tool for local governments. When used properly, a successful staff or team retreat can set an organization on a nearly unstoppable path of success. The experience can invigorate leadership, excite the community, and spark breakthroughs, although as many management professionals, including myself can attest, such experiences appear to be as rare as they are inspiring.

It doesn't have to be this way. Hundreds of local governments might embark on an annual retreat each year and the format and purpose of their event, much like the food, are often the same. This is true despite the fact that leaders recognize that their teams and their challenges are unique.

Success, then, starts with making better choices. If we choose to use the retreat as a means to address a group's biggest, most fundamental problems, the powerful, meaningful experience we've always hoped for can be created.

Educator and author Andrew Ballard, who is a chief growth strategist from Mill Creek, Washington, considers planning as the common thread from more than 500 retreats he has conducted. He says, "What makes for a productive retreat is the advance work, preparing and communicating an agenda, and providing insights that inform the planning participants."

Having been a retreat facilitator myself, I believe the right agenda also is the deeper, more difficult challenge and requires the right mindset from leadership.

Another expert, Eric Svaren, who taught courses on managing teams and group decision making at the University of Washington, agrees. Based on his work facilitating hundreds of retreats and also mentoring future facilitators, he knows firsthand the success that comes from this deeper level of preparation.

It was evident in one of his best retreats that was, in his words, "actually a summit." He worked for months with a design team made up of employees from all levels of a local government agency to plan how to engage employees in the project.

It led to a two-day event that he said "involved a wide range of activities and exercises that both dramatically increased trust (which was low) and set a clear direction for improving the culture. Years later, participants report that it was a pivotal event in the evolution of the department."

Design Choices

To have a design team work so closely on the retreat implies that there are design choices to be made. This concept of choices opens the retreat to become something far greater than it typically might be.

Retreats have been associated with the development of a plan for the next year. These planning exercises feature the same basic elements: visioning exercises that lead to a single, broad mission that is broken down into themes, then problems, then objectives, then solutions, and concluding with group voting exercises that lead to general consensus on a set of goals, objectives, and actions for the next year.

Such work is important and yet such work, by itself, seldom sparks the change or the energy an organization seeks. That is because this sort of planning-centric work—setting a vision, identifying problems, creating solutions, and so forth—often comes before other, more fundamental issues within the team have been properly resolved.

An ineffective team cannot be made whole by even the most effective retreat if the retreat does not address the right problems in the right sequence.

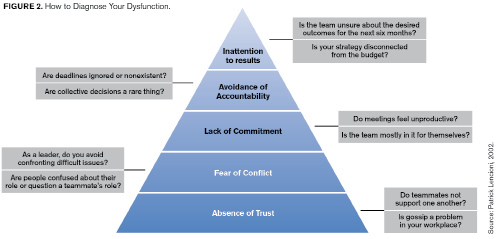

In his best seller The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, author Patrick Lencioni proposes a set of core needs that extends the human motivation theory of Maslow's hierarchy from the individual to the organization.

As a hierarchy itself, these dysfunctions and subsequent needs are presented in a pyramid (see Figure 1) to imply what must start first, at the foundation, in order to build layer upon layer to the peak.

The conventional retreat, built on the idea of planning the next year, is almost entirely focused on delivering results, which is at the top of the hierarchy. True to Lencioni's hierarchy, however, is the fact that results cannot be easily accomplished if the remaining, more foundational elements are weak.

The team simply can't support it. Dysfunctional teams, in other words, simply aren't ready for the conventional planning retreat they often find themselves in because their foundation is lacking. They need something different.

"Trust and respect are usually low in dysfunctional groups," Svaren says. "And when those are absent, it's all people think about." Anyone who has been part of a dysfunctional group knows this to be true. It's practically impossible to commit to a bold vision when you aren't sure if fellow teammates really support your role in the effort.

Similarly, if the team's leadership fails to hold people accountable, one would feel no enthusiasm to meet a new benchmark since there is no consequence of failure or incentive for success. Again, deeper issues of trust or doubt or conflict prevent any of the more normal retreat conversations regarding a new vision or future results from becoming meaningful.

Determining Your Group's Needs

Dysfunction on the level of Lencioni's pyramid is not easy to hide. Each of us can diagnose these issues rather easily with a few honest questions and some eyes-wide-open observation (see Figure 2).

Prior to designing a retreat, managers can think through these 10 questions to determine the group's needs. Consider the "everything in place" value of organizational development and make sure all ingredients are properly arranged before starting the work of making something great. If anything is missing, then the problem is apparent.

- Is gossip a problem in your workplace?

- Do team members not support one another?

- Are people confused about their role or question a teammate's role?

- As a leader, do you avoid confronting difficult issues?

- Is the team mostly in it for themselves?

- Do meetings feel unproductive?

- Are collective decisions a rare thing?

- Are deadlines ignored or nonexistent?

- Is your strategy disconnected from the budget?

- Is the team unsure about the desired outcomes for the next six months?

Each question is a test. If you cannot confidently say no to all 10 questions, then it is evident that the team isn't truly ready for a strategic planning retreat that is deeply focused on results. Instead, each question that generates a "yes" highlights a far more important, foundational issue that needs to be addressed first.

Once the issues are understood and a facilitator is in place, the rest is simply a matter of design. All great design comes from the proper understanding of the problem.

If the issue is a lack of trust in the group, the retreat must feature an earnest conversation on that matter supplemented with exercises that help each participant approach such a difficult issue in a more comfortable mode.

Leaders can be disappointed when they find their team isn't fully engaged in high-level tactical discussions that are associated with planning retreats. The lack of engagement in the issues that need to be addressed, however, doesn't mean there is no desire to engage. The lack of group readiness for one topic simply means team members are ready for something else, something equally important.

Which is to say that there is nothing faulty or wrong with a group that isn't ready for setting detailed workplans and benchmarks for the future. Group members simply have to grow into it, and this is what a retreat should be about: growth, progress, and a look to the future.

Some Basic Solutions

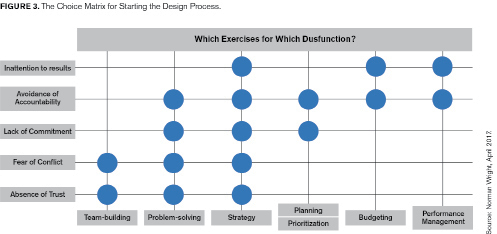

To further the idea of great design leading to great retreats, consider one final resource: a choice matrix. While Lencioni's pyramid points to a basic diagnosis of what dysfunction your team faces, the matrix in Figure 3 prescribes some basic solutions.

It expands the notion of a retreat to include several different types of activities, from the basic foundational elements of trust to the advanced focus on performance management.

Each exercise category has its own tasks, actions, and design decisions. Each requires the right sort of facilitator to guide the process. This can point in the right direction, but it is by no means an attempt to give a paint-by-numbers approach to designing a retreat.

Lencioni's pyramid combined with the matrix provides a leader with a basic sense of problems and solutions, but it can't be the sole method for designing the retreat itself. That will take more work.

Before investing time and effort in the next event, consider the team's readiness. Specifically: What sort of retreat are team members ready to have? Consider, too, the outcome you most desire to achieve. If you want something memorable, something that changes the course of a group and removes obstacles, be honest about what your team is grappling with and be sure you work on the right thing.

As author Stephen Covey famously said, "The main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing." For the vast majority of work groups, the retreat isn't the time to discover what the main thing is, per se. It is the tool to address it. When done correctly, it can work wonders.

Works Referenced

Lencioni, Patrick. The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002.

Ballard, Andrew. Personal interview, March 10, 2017.

Svaren, Eric. Personal interview, February 22, 2017.

Norman Wright is director, community and economic development, Adams County, Colorado (norman.wright@outlook.com). The author retains copyright to this article. He extends special thanks to Eric Svaren for his guidance in its preparation.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!