By Robert Eskridge, Kathryn Webb Farley, And Beth Rauhaus

Research has found that women manage differently from men in a number of ways.1 For example, women tend to encourage citizen engagement and input into decision making, and they lead in a less hierarchical and more participative manner than their male counterparts.2

According to ICMA member data, only a small percentage (18.4 percent) of female ICMA members report their title as “chief administrative officer (CAO).” A much higher percentage of women in ICMA (41.1 percent) claim titles of assistant or deputy CAO. Women constitute a little over half (50.6 percent) of ICMA members employed in all other local government positions.3 With the silver tsunami of coming retirements, these women are poised to be the community leaders of tomorrow.

We recently conducted a survey of women in the top management position in cities to gain a better understanding of the gender differences among these managers and how their professional and work experiences have helped to socialize them and influence their performance and their own perceptions of their role. Socialization helps individuals develop their beliefs about their role and appropriate actions.4 Specifically, we examine ways female and male managers differ, and whether, over time, differences in motivations, attitudes, and identities of women in city management disappear as they are socialized into the profession.

We conducted a survey of 353 female city managers/CAOs identified in a web search of 2,499 cities with a population of at least 5,000. We also surveyed 353 males in comparable positions. We then followed up with phone interviews with 23 male and female managers.

Survey Goals

The survey was designed to capture information about each manager’s attitudes, perceptions of his or her experiences, motivations, fiscal and social ideology, and confidence levels. For example, respondents were asked how prepared they felt for their position when they began; we also asked them to rate their ability to fulfill the job responsibilities, their decision-making ability, and related indicators. We used this information to create an index measurement to capture their level of confidence in their abilities.

We also captured personal demographic information in addition to gender: education, family status, age, race, and number of years they have served as a city manager/CAO. In addition, we asked respondents whether they felt adequately mentored before becoming a manager (see Table 1).

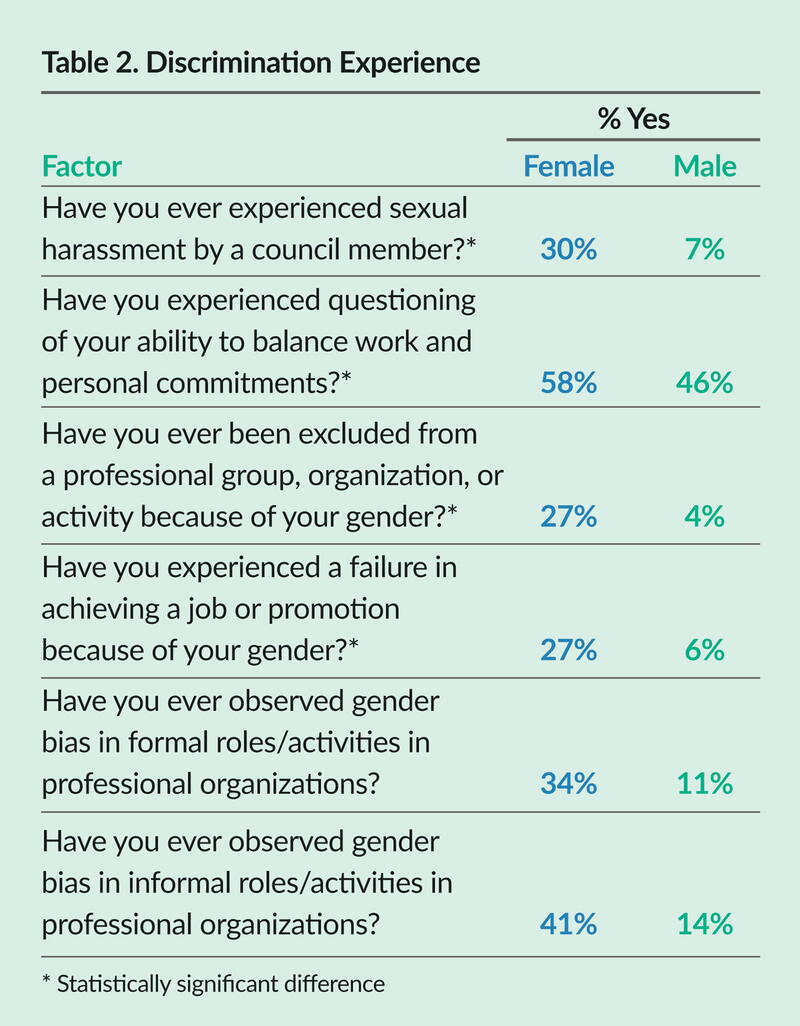

To determine whether managers had ever experienced bias or discriminatory behavior in their work or professional organizations, we asked about each respondent’s personal experiences with gender-related issues, such as sexual harassment or professional bias such as exclusion from professional activities or failure to acquire a position.

From the responses, we identified differences and similarities between males and females in our survey.

Key Gender Differences

Women tended to be younger, and slightly fewer women had a master’s level education. More women than men felt that they had not been adequately mentored before becoming a manager. Women had also served in the chief appointed management position for a significantly shorter time period than men (almost 37 percent of women had served for five years or less compared to only 25 percent of men).

This is not unexpected when we observe that women are significantly more likely to be serving in their first city manager position (65 percent of women versus 46 percent of men). This may also help to explain why we find that 41 percent of women serve in communities of 5,000 to 10,000, while only 27 percent of men serve in these smaller communities. Interestingly, only 41 percent of women reported having children living at home compared to 57 percent of men. This could indicate that women in this career choose not to have children or that they delay having a family until they are established in a career.

We did find a number of significant gender differences when we examined respondents’ experience of discrimination in the workplace and in professional organizations (see Table 2). Women are much more likely than men to have experienced sexual harassment by a councilmember (30 percent of females); had their ability to balance their personal and work life questioned (58 percent of females); and to have experienced gender bias in formal (34 percent) and informal (41 percent) roles/activities in professional organizations. Females also significantly differed from males in failing to be offered a job or achieving a promotion because of their gender (27 percent versus six percent) and being excluded from professional groups or activities (27 percent versus four percent). These different professional experiences may have lasting effects on women’s approach to and understanding of their working environment.

Confidence Issues

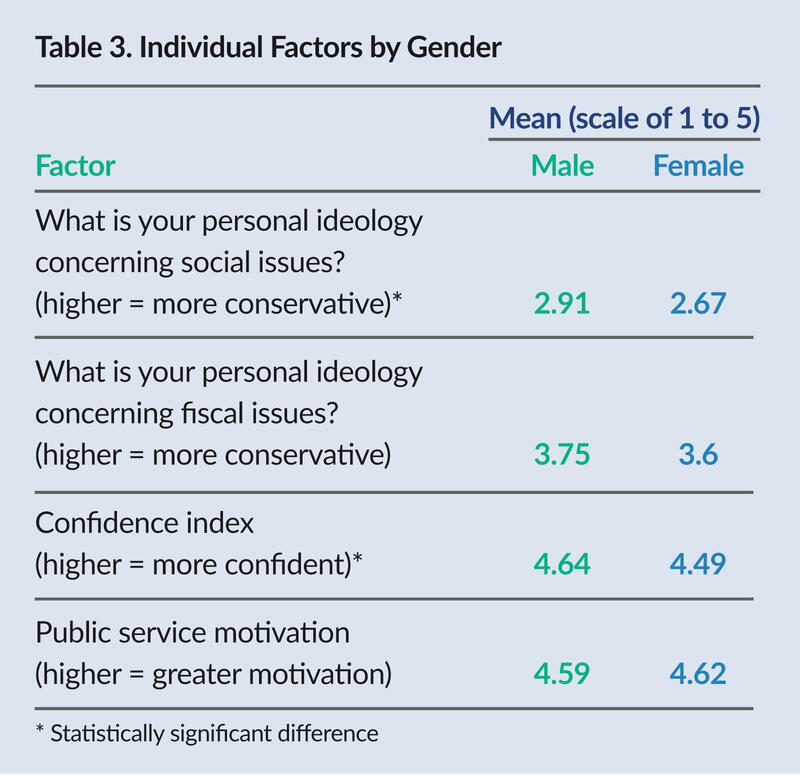

We found women managers to be less conservative than their male counterparts, significantly so for social issues (see Table 3). Interestingly, years of experience in the job has a liberalizing effect for women but not for men (not shown in table).

Overall, female managers scored significantly lower than male managers in confidence levels. Perceiving that one was adequately mentored had a positive effect on confidence, but having experienced bias in formal roles of professional organizations had a negative effect.

Again, we discovered that when we look at the combined effects of gender and years of experience, a highly significant relationship exists. Women with less than one year of experience had less confidence than men. Women with more than 20 years of experience had higher levels of confidence than men.

Years of experience appears to have a positive effect on the confidence level of women but not of men. Interviews suggest this may start in the hiring process. Several women with fewer than 10 years of service indicated that they felt they were perceived as less fit for the job than a man or that they were questioned about work/life balance during interviews. Others recalled a council or citizens questioning how they would balance a family and work.

This trend may continue early in a woman’s career and then change. For example, one woman with fewer than 10 years’ experience recounted how she had reached out to ask her peers a question and that “it was interesting how quickly the women city managers reached back to me; a lot of times the male city managers delegated correspondence to [another] office instead of answering me directly from one city manager to another.”

Another indicated that although she had been city manager throughout most of the duration of a major building project, the city council recognized previous managers during the grand opening but failed to publicly acknowledge her leadership during the event. A woman with more than 10 years’ experience said, “I recognized early on that I couldn’t be the same type of city manager as a strong male person. I did not have the overbearing presence. I needed to figure out what my own strengths were and play to those.”

There are two possible explanations for women’s increase in confidence with years of experience in comparison with men. One explanation is that although males’ confidence levels do not change with experience, females do gain confidence with experience. Alternatively, it may suggest that newer female city managers are entering their positions with less confidence than women who entered the workforce in past years. A future detailed study will be necessary to draw further conclusions; however, either explanation suggests that some type of socialization is at work.

Valuable Lessons

Overall, our study highlighted gender differences that exist today in local government management, which may be helpful in further understanding gender disparity at all levels of government, the distinct impact of women in government, and the barriers they face. By examining gender differences among city managers, we can also further understand how women affect governance at the local level and perhaps at the state and federal levels as well.

Survey and interview data both indicate that the effect of adequate mentoring may be one of the most significant ways men and women differ. Moreover, inclusion in professional associations and networks may also have gender-related effects.

These findings can offer valuable lessons for today’s managers. Ensuring that young women in the profession receive adequate mentoring is extremely important, but it appears to be only part of the solution. Developing the appropriate norms, behaviors, and skills that are associated with confidence in one’s ability to do a job also appears linked to associating with other managers.

Most men indicated that professional associations had been helpful. In our survey, very few men indicated they had ever felt excluded from these groups, and no men in our follow-up interviews indicated this. In contrast, more than half of the female interviewees indicated they had felt excluded or treated differently.

Part of the solution may be helping women form relationships across the state or region and making sure someone reaches out to new managers, either at the time of appointment or during conferences, and welcomes them as colleagues. It could be that as confidence increases, so does the feeling of belonging to the profession.

The Massachusetts Municipal Management Association (MMMA) is in the process of developing a mentorship program that may start to address this gap in the socialization of women. MMMA has created a women’s mentoring group and asked all members to invite women who may be future city managers or department directors to attend the meetings. This could help individuals learn the norms, behaviors, and skills they need and also build networks that will help them feel adequately mentored and included.

Our study’s findings offer important insights given the importance of attracting women to the local government management profession and supporting them in their careers.

Endnotes and Resources

1 Fox, R. L., & Schuhmann, R. A. (1999). Gender and local government: A comparison of women and men city managers. Public Administration Review,59(3), 231- 242.

2 Meier, K.J., O’Toole, L., and Goerdel, H. (2006). Management activity and program performance: Gender as management capital. Public Administration Review66: 24-36

3 International City/County Management Association. Membership data. August 20, 2019.

4 Berger, P. L. & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge.Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!