From the November 2020 LGR: Local Government Review supplement in PM magazine:

Trust in government and in politicians is a very crucial prerequisite for democratic processes. This is true not only for the national level of government, but also for the regional and local levels. We make use of a large-scale survey among citizens in Denmark to evaluate trust in politicians at different levels of government. And we find that trust in local politicians is somewhat higher than trust in members of Parliament (MPs)—especially among citizens who are well satisfied with the municipal service delivery.

By introducing several municipal-level variables in a multi-level analysis (MLA), it is also found that very chaotic government formation processes can negatively influence trust in the mayor and the councilors. Reaching out for local power by being disloyal to one’s own party or by breaking deals already made can sometimes secure the mayoralty, but it comes at a cost: lower trust among the electorate.

Political Trust in a Multi-Level Setting

The defining feature of representative democracy is the representative connection between voters and elected representatives by which voters elect politicians who then make decisions on their behalf until the next election, when voters then evaluate the representatives by voting them in or out of office (Manin, 1997; Przeworski et al., 1999; Trounstine, 2010). In its simplicity, this vital mechanism for representative democracy looks ingenious at first, but it is worth noticing how radical the idea of representational democracy is. For an extensive period of time (in many cases, four or five years) the many voters allow the few politicians to rule them and let them make sometimes critical political decisions on their behalf. Deliberative arrangements, which make discussions between citizens and politicians possible in between elections, are, of course, also a part of the representative democratic set-up in many countries, but what basically keeps the system together and enables political representation as a continuously working form of democracy is trust. If the voters trust the politicians and the political institutions, then the system is viable and can survive; otherwise it will be seriously challenged. And in a world where representative democracy in many countries is seen as the preferred form of democracy, it is therefore essential to monitor the level of the citizens’ trust in their representatives and in the legislatures these politicians inhabit.

Therefore, it is no surprise that the concept of political trust has been discussed and researched extensively for many years (e.g., Easton, 1965; Miller, 1974; Bianco, 1994; Norris, 1999; Levi and Stoker, 2000). The definitions of trust are many; for now we will follow Miller and Listhaug who state that: “Trust…reflects evaluations of whether or not political authorities and institutions are performing in accordance with normative expectations held by the public. Citizen expectations of how government should operate include, among other criteria, that it be fair, equitable, honest, efficient, and responsive to society’s needs. In brief, an expression of trust in government (or synonymously political confidence and support) is a summary judgement that the system is responsive and will do what is right even in the absence of constant scrutiny” (Miller and Listhaug, 1999).

We fully acknowledge that several different dimensions of political trust can be identified, but instead of getting involved in that discussion, we will stick to the definition’s point that trust is a kind of “summary judgment.” And therefore, throughout the article, we will take for granted the summary judgment of the citizens that we have surveyed—if they say that they have trust in politicians when asked directly, we will trust their evaluation.

We will take the discussion and the empirical analysis in a very specific direction, since we also find it important that this concept and the empirical understanding hereof is more multi-level in nature than what has previously been seen. Despite more and more focus on multi-level governance (Bache and Flinders; Piattoni, 2010), it seems that in most cases this means including the supranational level (e.g., the European Union), whereas the local government level continuously is, if not outright forgotten, then somewhat overlooked in many branches of political and administrative science.

Focusing on the Local Level

The scarcity of studies on political trust at the local level might have something to do with the tendency to pay less attention to “low politics” compared to “high politics.” Local governments often take care of roads, sewage, water, zoning, and other “technical” matters, whereas economic policy and foreign policy are decided at the national level and in the national political realm, sometimes even in supranational spheres. (Although in many countries, local governments are often in some ways involved in important policy fields such as schools, social services, and care for the elderly). However, without taking sides in the debate on whether local or national governments are the most important, it could be argued that more attention should be paid to the local government level. In all countries there are by far more politicians elected at the local level than at the national, and therefore it seems a bit peculiar not to take these many local politicians into account when political trust is discussed. Also, by including the local level in the analyses of political trust, we get a better empirical understanding of this specific political/administrative phenomenon. Not only does the local level supply us with more cases to scrutinize, it also offers a unique comparative basis of analysis. We might be able to learn from comparing trust at different political levels within the same country and learn from the comparison different local governments within the same country, thereby being able to have many comparable cases (Lijphart, 1975).

Paradoxically, the sheer number of local governments not only makes them interesting from a scholarly point of view, it sometimes also makes them less accessible for scholars since data on local governments are often harder to access compared to data on national governments. Precisely because of data scarcity, it has been concluded, in regard to the study of trust, that: “The extant literature is thus ill equipped to comment critically on the nature of public trust in local government” (Rahn and Rudolph, 2005: 531). But data on local government can be produced, and therefore we will accept the challenge and partake in an MLA on trust in governments.

We will do this by asking two questions. First, we will ask where the level of political trust is highest—at the national, regional, or local government level? Second, we will focus on the local government level and try to explain the variation across different municipalities. This is in line with Rahn and Rudolph when they ask: “Why is local political trust higher in some places than in others?” (2005: 531).

We will conduct the study as a single country study (comparing across levels and local governments) and have chosen Denmark as our case. The reason for the case selection is mostly related to the unique data situation in Denmark. The official statistics on the regional and municipal level are among the best in the world (since most official statistics are split by region and municipality). Also, and most importantly, it has been possible to conduct several large-scale surveys among Danish citizens over the years—surveys where the number of respondents in each municipality has been sufficiently high to apply MLA to the data.

Denmark consists of 98 municipalities and five regions so that every Dane votes for three elective bodies: municipal council, regional council, and national parliament (Folketinget). In a survey conducted in 2013, we asked 4,902 Danes about their level of trust in these three institutions and their level of trust in the politicians at each of the levels (municipal councilors, regional councilor, and MPs). We have sampled at least 30 respondents in each municipality so that variables at the municipal level can be included in multi-level analyses.

In the next two parts of the article, we will use this unique dataset to answer the two questions posed above. In the first part, we will compare the trust among the citizens to different levels of government and in the next part we will explain the variation in the trust of local politicians between citizens living in different municipalities.

The Lower the Level of Government, the More Trust?

Does citizen trust differ depending on which level of government is under scrutiny? And if so, which level of government receives the highest level of trust? The hypothesis derived from the literature is quite clear: “Trust is anticipated to grow as it becomes closer in spatial scale—thus, the more local, the higher the trust” (Petrzelka et al., 2013: 338). It is claimed that it is distance between the citizen and the politicians/administrators that can potentially create mistrust, and from this premise it follows that trust is relatively higher at the local government level than at the regional and national level of government. The claim has been made by several authors (e.g., Jennings, 1998; Levi and Stoker, 2000; Cole and Kincaid, 2001) and it has also found some empirical support (Cole and Kincaid 2000), although the evidence is not conclusive (e.g., Petrzelka et al. 2013).

The argument that trust is higher at the lower levels seems sound and consistent with the tendency not to trust strangers; the larger the jurisdiction, the farther away the political/administrative system will ceteris paribus be to the average citizen, in terms of physical distance and in more figurative terms, and therefore the politicians will be less known and thereby less trusted. However, this line of argument could also be challenged. First of all, some people might actually trust strangers. Secondly, the way citizens get to “know” their politicians is not only by meeting them in person—today most people probably “know” their politicians from the media. Thirdly, by hypothesizing that the closer the citizens are to their politicians, the more they trust them, it is more or less implied that knowledge can only be advantageous for the way citizens perceive politicians, thereby neglecting that information can also reveal less trustworthy traits of the politicians.

Therefore, the question of trust at different levels of government is more an empirical question. When surveying citizens’ trust, it is, however, important to make a few distinctions. A distinction can be made between trust in the politicians and trust in the institutions—it is possible to trust the parliament as an institution without trusting the MPs currently serving there, and vice versa. Also, politicians are different—some of them are not only representatives but also hold executive power and/or a leadership position.

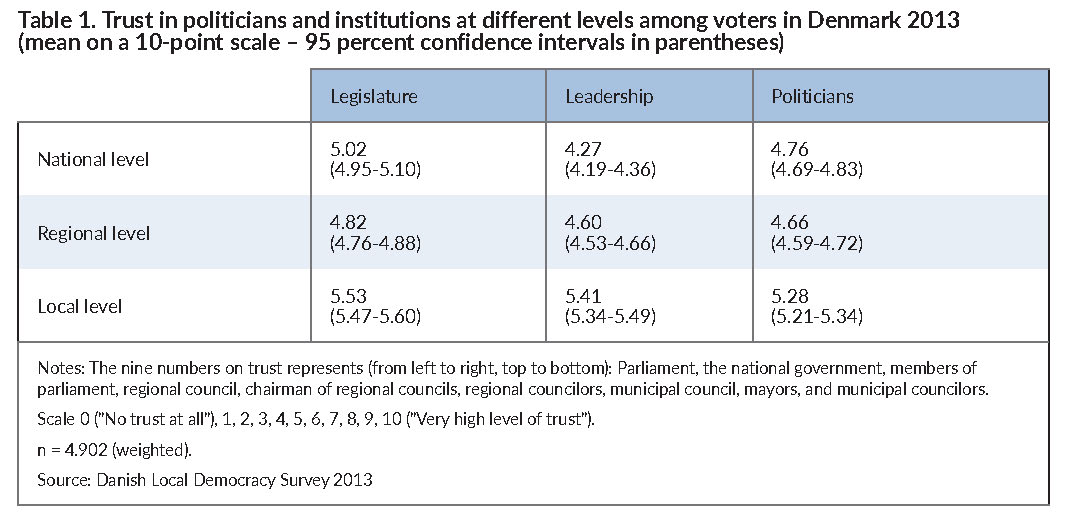

Therefore, in the Danish case, we have asked the citizens about their trust in the parliament as an institution, the MPs, and those MPs who hold a leadership position. And we have asked about their trust in these three institutions/politicians at the national, regional, and local government level, respectively. The results in terms of the average level of trust for these nine groups, based on the survey conducted in Denmark, are reported in Table 1.

As demonstrated in Table 1, Danish citizens’ trust in their politicians and the institutions they inhabit is not that overwhelming. On the 10-point scale applied, most of the results are around the middle of the scale, indicating that Danes in general are not mistrustful of their politicians, but they do not trust them a lot either.

For all three levels of government, it is also demonstrated that the trust in politicians is a little lower than the trust in the corresponding legislatures. The differences are not huge, but as it can be seen in Table 1, they are statistically significant. Citizens trust their national parliament, their regional parliament, and their local parliament to some extent, but they trust the politicians who are presently holding the seats there a little less. As for the leadership, the findings are inconclusive.

For our purpose, the most interesting finding reported in Table 1 pertains to trust across levels of government. No matter whether we analyze trust in legislatures, leadership, or politicians, a clear pattern can be observed: The citizen’s trust in the local government level is higher than the same citizen’s trust in the regional and national level of government. The difference is not huge, but it is statistically significant. So, in the Danish case, the traditional hypothesis claiming higher trust at the local level cannot be rejected.

Who Trusts Local Politicians the Most?

Not all the citizens have the same level of trust in their politicians. Therefore, we will move on to the second question posed in the introduction, namely: Who trusts their politicians the most? We will focus on the local politicians—the councilors—since this will allow us to search for explanations also at the institutional level. Studies of trust have already included several individual-level variables, but our claim is that not only is the individual interesting in that respect, but the political jurisdiction where this individual is living can also be important for our understanding of the individual’s evaluation of the political jurisdiction and its politicians. We will follow Rahn and Rudolph who state, “[Trust]… cannot be explained solely by accounting for variation in the attributes and attitudes of the individuals who live in each city” (Rahn and Rudolph 2005: 531) and have as our main focus to expand the analysis by also including institutional-level variables.

We will, of course, in our models, still include variables at the individual level, but they will mostly serve as controls. These individual-level variables will be the “usual suspects”; that is, variables that are often included in studies of trust (Levinsen, 2003). We will include in our analyses a number of sociodemographic variables, namely age, education, employment sector, and income, hypothesizing that older, more educated, higher-income citizens, as well as those employed in the public sector, will have higher trust than their counterparts. We will also include a number of attitudinal variables, namely how informed the individual is about local politics, their interest in local politics, their satisfaction with the municipal services provided, and their general trust in other people (social trust), hypothesizing that the more informed, the more interested, the more satisfied, and the more socially trusting, the more the individual will trust their local politicians.

Then there is our additional claim, namely that explanations to the variation in trust should also be examined at the institutional level—in this case, at the municipal level. Already, two municipal-level variables have been introduced in the literature. First, at least since Dahl and Tufte’s seminal book on size and democracy (Dahl and Tufte, 1973), there has been an interest in the potential effect of the municipal size (in terms of the number of inhabitants) on different dimensions of local democracy. Politicians are supposed to be more responsive in smaller democracies (Dahl and Tufte, 1973: 12ff), leading to more trust in smaller municipalities than in larger. And even though there has not been a lot of empirical testing of the “small is beautiful”-thesis (Petrzelka et al. 2013), some studies have found a negative correlation between municipal size and citizen trust (Rahn and Rudolph, 2005: 547; Denters, 2002; see however Levinsen, 2003). Therefore, the following is our first hypothesis at the municipal level: Hypothesis 1: The larger the municipality, the lower the citizens’ trust in their local politicians.

Municipal size is one thing—another is if the municipality has recently merged with other municipalities and therefore if citizens have experienced a change in the size of their municipality. If an amalgamation has been implemented, the citizen may have lost some of their faith in the councilors; for instance, in some cases councilors may no longer live in the citizen’s own village or neighborhood. Even though reform effects are in some studies discarded (Reitan et al., 2015), a negative effect of municipal mergers on citizen trust has been empirically demonstrated (Hansen, 2013), and therefore our second hypothesis is: Hypothesis 2: If the municipality has recently been part of an amalgamation, the citizen’s trust in their local politicians will be lower.

As clever and insightful as Dahl and Tufte’s book on size and democracy is, it has, however, also led to a tendency to focus almost exclusively on the question of size when dimensions of local democracy are evaluated (e.g. Denters et al., 2014; Kjaer and Mouritzen, 2003). We will, however, also go beyond size and include specific political variables. First, we will include the level of political conflict in the municipality; if the politicians regularly engage in infighting, it might lead to higher levels of mistrust among the citizens. It is often claimed that local politics is more consensual than politics at other levels (Barber, 2013), and not least in Denmark where local politics has been assessed as being very consensual with a widespread norm of consensus (Berg and Kjær, 2009). The most important determinant of how consensual politics is conducted in the municipalities is supposed to be the width or breadth of the coalition forming the majority behind the mayor (the mayor is indirectly elected by and among the councilors), and therefore, our third hypothesis is: Hypothesis 3: The broader the mayoral coalition, the greater the citizen trust in local politicians.

When there have been negative stories about the councilors and the mayors in Denmark in the past years, it has mostly been regarding the coalition formation processes. At the 2009 local elections (the latest election before our survey was administered in spring 2013), several municipalities experienced unusually chaotic formation processes characterized by extreme political tumult. In no less than 10 out of the 98 municipalities, a situation occurred where the coalition formed right after the election was cancelled and a new one formed before the original coalition was formally put into effect. In some of these cases, councilors left their own party to join the opposing party (and get the mayoralty themselves). The stories from the 10 municipalities differ slightly (see Elklit and Kjaer, 2013), but what they have in common is that they were intensively covered by local and national media, and the citizens were in most cases not only surprised but also somewhat offended by the councilors failing to respect the electoral result and not honoring their own original deals with each other. Therefore, our fourth hypothesis is: Hypothesis 4: In municipalities where the coalition formation process at the latest election was extremely chaotic, the citizen’s trust in their local politicians will be lower.

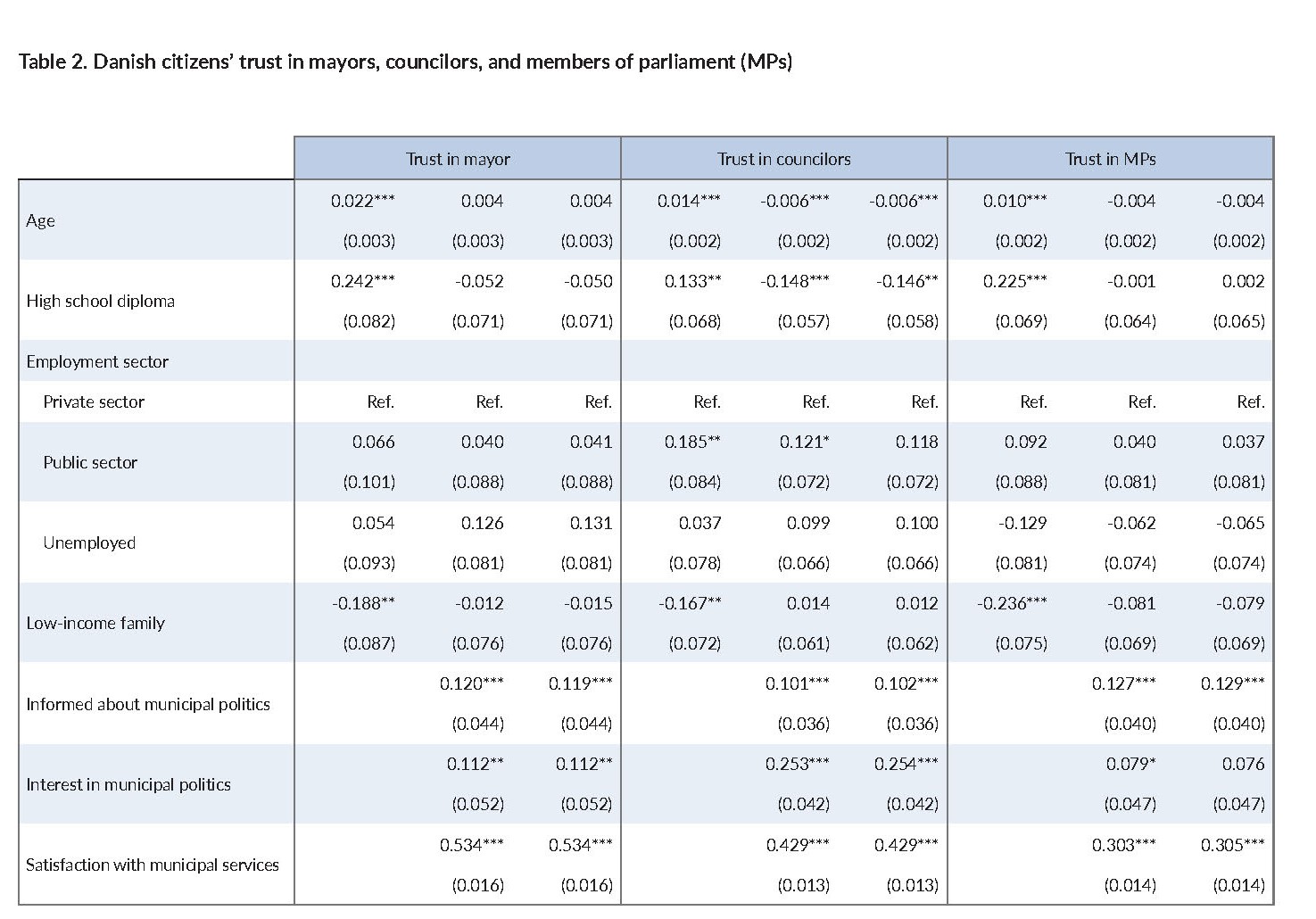

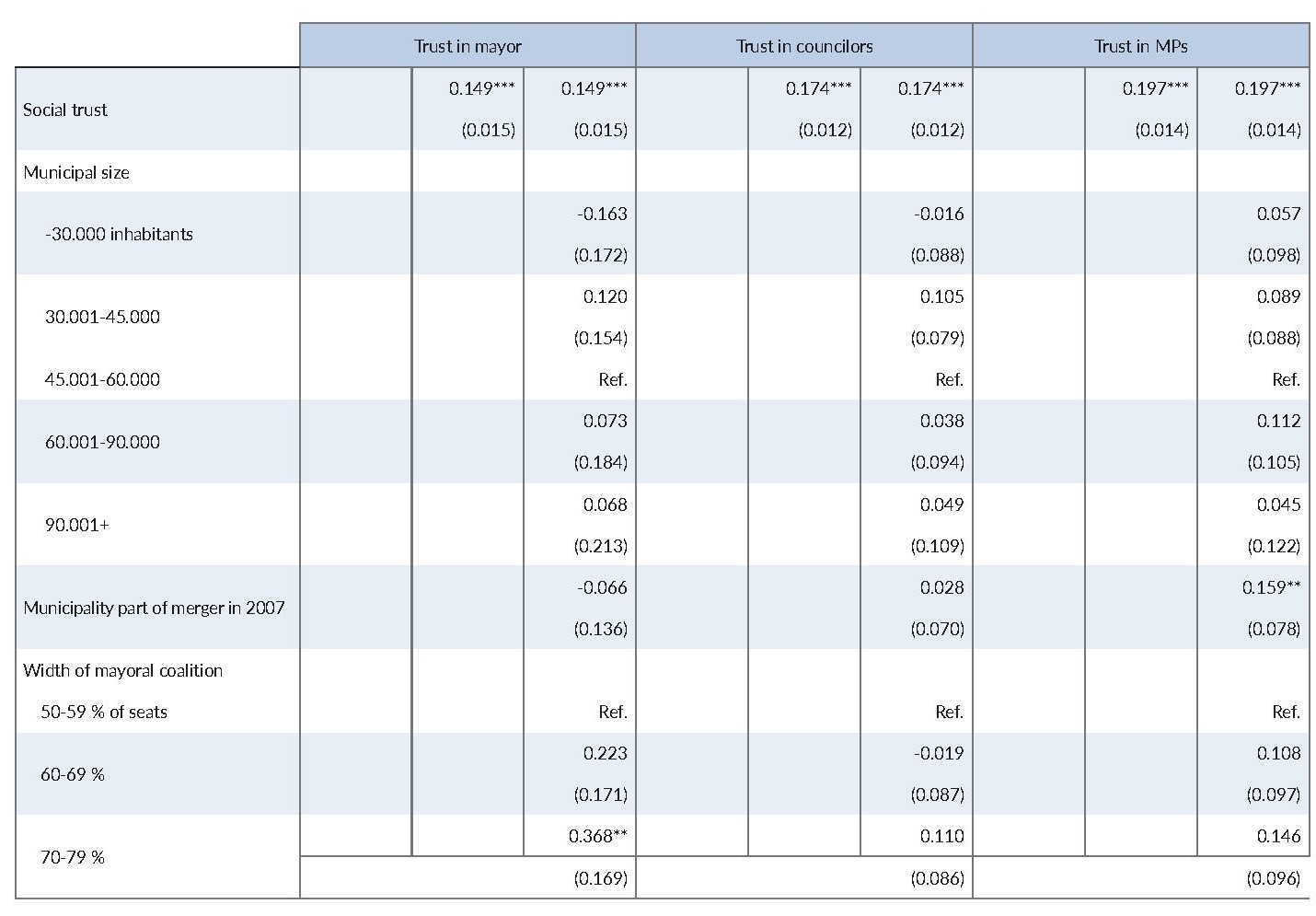

We have run three different models including these variables stepwise. In the first model, only the sociodemographic explanatory variables are included, while in the second model, the attitudinal variables and individual-level variables are also included. In the third model, the municipal-level variables are also included, making it possible to test our four hypotheses (therefore, this third model is run as an MLA).

We run each of the three models using three different dependent variables, namely trust in the mayor, trust in the councilors, and trust in MPs (the last one as a control). The results are reported in Table 2, found at the end of this article.

In Table 2, it can be seen that among the individual-level variables, the attitudinal variables are far more important than the sociodemographic ones. None of the sociodemographic variables are significant in the model explaining trust in the mayor, when the attitudinal variables are included, and only minor effects (negative ones) are found regarding age and education in the model explaining trust in councilors. The explanatory power of the attitudinal variables is much higher—a clear and statistically significant positive correlation with trust in mayors and councilors is found for level of information, interest in local politics, satisfaction with local service, and general social trust. This is more or less as expected (see also Levinsen, 2003).

But how about the four variables at the municipal level? Table 2 demonstrates that our first and second hypotheses can be rejected without much further discussion. There is no statistically significant correlation between municipal size or municipal mergers and trust in the local politicians, regardless of whether it is trust in the councilors or in the mayors.

As for the size of the mayoral coalition—hypothesis 3—the results are not conclusive, but it is demonstrated that if the mayor can form a very broad coalition including the entire council (this actually sometimes happens in Denmark) he or she will gain more trust from the citizens. However, the causal mechanism here cannot be established, since a very trustworthy mayor probably has better chances to form a broad coalition.

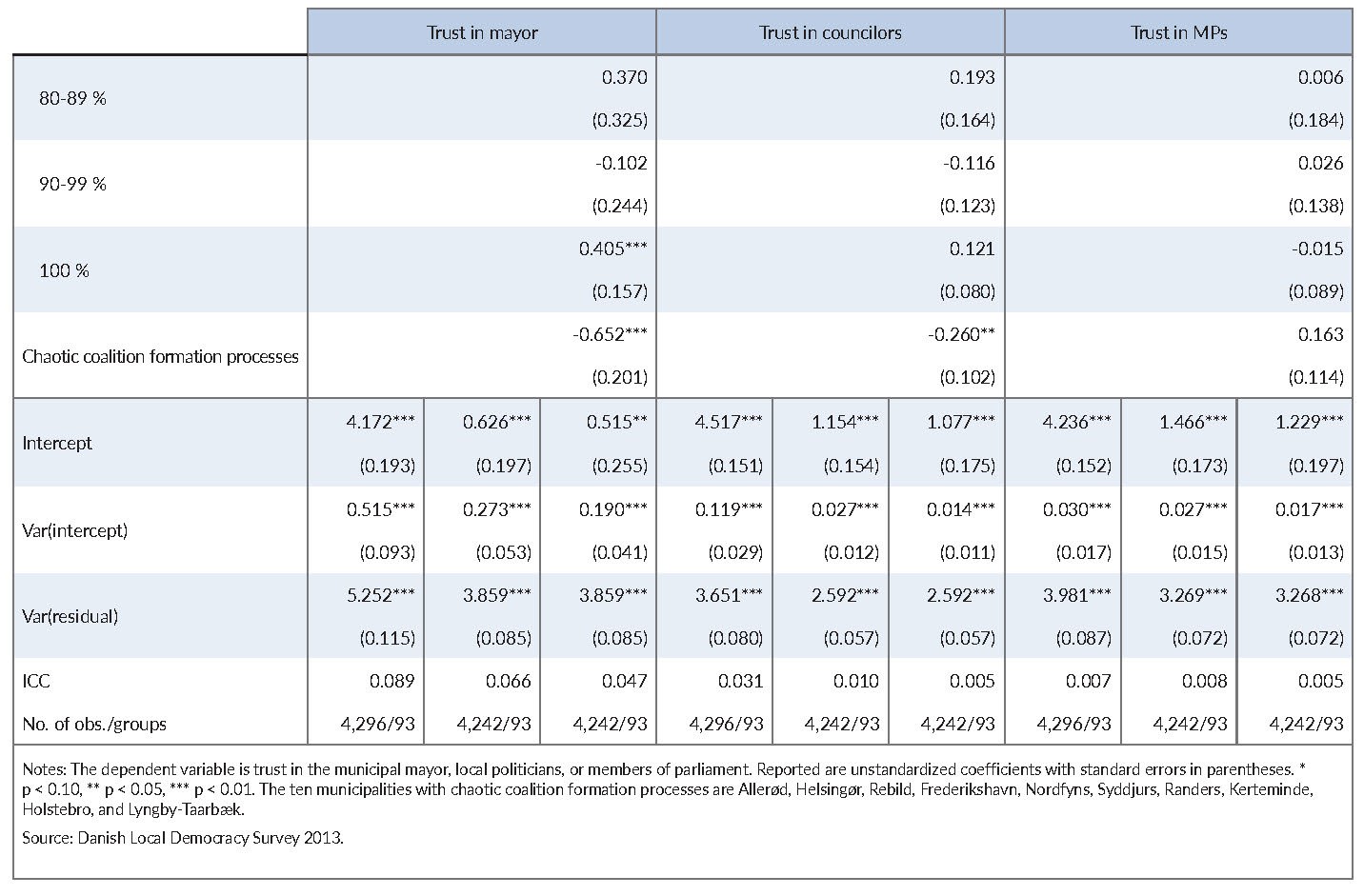

This leaves us with the chaotic coalition formation processes—Hypothesis 4—and here the results are very clear. As Table 2 demonstrates, trust in local politicians is—even three years after the events—lower in municipalities where the mayoral coalition was formed under very chaotic and politically “bloody” circumstances. In the municipalities where some of the politicians violated done deals, shifted party, and behaved disloyal to their political allies, the citizens trust their politicians less than in municipalities where everybody played by the rules and where the government formation was conducted, as they usually are, in a calm, orderly manner.

The lower level of trust is clearer regarding trust in the mayor than regarding trust in the councilors. The mayor who wins the mayoralty in a process characterized by tumult pays a price in terms of lower trust, but also the councilors in general are punished when the citizens afterward evaluate how trustworthy they are. In Table 2, the same models are also run with trust in MPs as the dependent variable, and it is seen that, as hypothesized, this trust is not affected by the chaotic coalition formations, which strengthen the finding.

As a robustness check, we have also run the models with the difference in trust of politicians at the local and national level as the dependent variable. This analysis is therefore targeted on the difference in trust—who is it who trusts their local politicians relatively more than their national politicians? In these analyses a few of the findings from Table 2 are moot, but most of the findings are repeated in this relative analysis, not least of which is that the degree of satisfaction with the municipal service is still important to the level of trust. If local councilors and mayors would like to have their constituents to trust them, they should focus on the delivery of municipal services. And then there is the issue of chaotic coalition formations, a variable in this model that is highly statistically significant. And the negative effect is still greater on the trust in mayors than on the trust in councilors. The chaotic coalition formation processes have given the mayor the office, but not without costing them the trust of the citizens. The citizens trust the mayors who conquered mayoral office in an atmosphere of tumult less than mayors who avoided this chaos, and the councilors in these municipalities also pay a price for being partakers or at least bystanders in the chaotic processes.

Conclusion: Increasing Citizen Trust in Local Governments

This article has demonstrated that the citizens trust their local politicians—mayors and councilors—more than they trust their national politicians in the country of Denmark. This is not very surprising since this is in accordance with the general perception that trust increases when the level of government decreases. Therefore, we have also devoted a part of this article to analyze citizen trust across municipalities; even though the trust in local politicians is relatively high compared to other levels of government, it is not equally high in every municipality. Several variables at the individual level have been included in the analyses together with a number of variables at the municipal level, namely size, merger status, coalition breadth, and chaotical coalition formation.

The findings are that trust in local politicians is affected by the experienced level of satisfaction with services delivered by the municipality (the more satisfied, the more trust) and then, more surprisingly, by how the coalition formation process was conducted (if chaotic, then less trust).

This indicates, that if trust in local governments is to be increased, there are at least two important ways to do so. First, results matter and therefore the municipality should focus on delivering the highest quality of service. In Denmark, the municipalities are in charge of, for instance, day care, primary schools, social services, elderly care, housing, planning, and water/sewage, and they should focus on these tasks. This goes for the politicians themselves who are involved in many of the decisions—especially the more detailed ones—through their seats on committees. And it also applies to the administrative officers and the people employed at the municipality; local government administration should optimize delivery of municipal services so that the municipality and the politicians will be trusted.

Second, the paper has demonstrated that the very chaotic coalition formation processes seen in a tenth of the Danish municipalities at the 2009 elections were not without costs. The political game can be muddy, bloody, and chaotic and it produces political winners and losers when the game is over and the prizes are distributed (not least, in the mayoral office). The politicians are, of course, very involved in these processes and they will go to great length to secure themselves the best rewards. But it seems that councilors and prospective mayors can also be too tactical and too determined to achieve power. If they break done deals or are disloyal to their own party, it comes at a cost since the citizens do not like this kind of game and lower their level of trust in politicians acting in this way. The message is clear for councilors and prospective mayors: Follow the rules and avoid chaos because your constituents are watching, and their trust is at stake.

References

Bache, Ian and Flinders, Matthew (eds.) (2004). Multi-Level Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barber, Benjamin (2013). If Mayors Ruled the World. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Berg, Rikke and Kjaer, Ulrik (2009). “Facilitation in Its ‘Natural’ Setting: Supportive Structure and Culture in Denmark” in James H. Svara (ed.) The Facilitative Leader in City Hall: Reexamining the Scope and Contributions, pp. 55-72. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Bianco, William T. (1994). Trust – Representatives and Constituents. Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press.

Cole, Richard L. and Kincaid, John (2001). “Public Opinion and American Federalism: Perspectives on Taxes, Spending and Trust,” Spectrum: The Journal of State Government 24: 14-18.

Dahl, Robert A. and Tufte, Edward R. (1973). Size and Democracy. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Denters, Bas (2002). “Size and political trust: Evidence from Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United Kingdom,” Environment and Planning C Government and Policy 20: 793-812.

Denters, Bas, Goldsmith, Michael, Ladner, Andreas, Mouritzen, Poul Erik and Rose, Lawrence E. (2014). Size and Local Democracy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Easton, David (1965). A Systems Analysis of Political Life. New York: Wiley.

Elklit, Jørgen and Kjaer, Ulrik (2013). KV09. Analyser af kommunalvalget 2009. Odense: University of Southern Denmark Press.

Hansen, Sune Welling (2013). “Polity Size and Local Political Trust: A Quasi-experiment Using Municipal Mergers in Denmark,” Scandinavian Political Studies 36: 43-66.

Jennings, Kent M. (1998). “Political trust and the roots of devolution” in Valerie Braithwaite and Margaret Levi (eds.) Trust and Governance. New York, Russel Sage Foundation.

Kjaer, Ulrik and Mouritzen, Poul Erik (2003). Kommunestørrelse og lokalt demokrati. Odense: University of Southern Denmark Press.

Lijphart, Arend (1975). “The Comparable-Cases Strategy in Comparative Research.” Comparative Political Studies 8: 158-177.

Levi, Margaret and Stoker, Laura (2000). “Political Trust and Trustworthiness,” Annual Review of Political Science 3: 475-507.

Levinsen, Klaus (2003). “Kommunalpolitisk tillid” in Ulrik Kjaer and Poul Erik Mouritzen (eds.), Kommunestørrelse og lokalt demokrati. Odense: University of Southern Denmark Press.

Manin, Bernard (1997). The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, Arthur H. (1974). “Political issues and trust in government: 1964-1970,” American Political Science Review 68: 951-972.

Miller, Arthur. H. and Listhaug, Ola (1999). “Political performance and institutional trust” in Pippa Norris (ed.) Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, pp 204-216. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Norris, Pippa (ed.) (1999). Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Petrzelka, Peggy, Marquart-Pyatt, Sandra T. and Malin, Stephanie A. (2013). “It is not just scale that matters: Political trust in Utah,” The Social Science Journal 50: 338-348.

Piattoni, Simona (2010). The Theory of Multi-level Governance – Conceptual, Empirical, and Normative Challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Przeworski, Adam, Stokes, Susan C. and Manin, Bernard (1999). Democracy, Accountability, and Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rahn, Wendy M. and Rudolph, Thomas J. (2005). “A tale of political trust in American cities,” Public Opinion Quarterly 69: 530-559.

Reitan, Marit, Gustafssona, Kari and Blekesaunea, Arild (2015). “Do Local Government Reforms Result in Higher Levels of Trust in Local Politicians?”, Local Government Studies 41: 156-179.

Trounstine, Jessica (2010). “Representation and Accountability in Cities,” Annual Review of Political Science 13: 407-423.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!