Leadership: what used to describe a behavioral trait is now an overused marketing term and the title of an entire industry. In a time of “selfie leaders” (those who humble-brag while posting images of themselves “leading” as an example of their credibility) and an endless sea of consulting firms that teach the newest leadership principles by self-proclaimed experts, the “leadership Industry” has morphed into a convoluted smorgasbord ranging from legitimate mentors to dazzling self-promoters with dubious substance and credentials.

The double-edged sword of social media sometimes undermines a leader’s positive intent to show transparent communication to their community or stakeholders. Leaders can send a counterproductive message when promoting servant leadership when they post the random picture of doing line-work purely as a photo opp. In an attempt to show that they are connected to their lower-level employees, the leader runs the risk of sending the exact opposite message. The invaluable hardworking but unglamorous and under-sung line staff, especially the nose-to-the-grindstone veterans, may see this as “look-at-me leadership” rather than what it was intended to be: a genuine example of a leader trying to connect with lower-level staff.

It is hard for the follower to appreciate the imperative leadership qualities of humility and authenticity when leadership “experts” are promoting their craft through selfies showing themselves gazing off into the distance at a sunset or coastline with a dramatic look of introspection, accompanied by a quote such as “leaders need to take time out to take care of themselves.” Or, a photo of their latest educational accomplishment with a statement about the value of being a “lifelong learner.”

A leader should consider that their behavior sets the expectations for the future leaders within their organization. Will those future leaders place a higher value on self-promoting social media posts rather than placing positive attention on others? If you are familiar with the work of James Collins and his book Good to Great, these little traits make all the difference in being a humble, effective, selfless leader…and follower. Collins dubs this type of aspirational leadership “level-five leadership.” 1

To be fair, we have all done it—but there is a fine, bright line between the desire to promote your organization, showcase your team, or highlight your professional experience, and coming across as self-absorbed. There are circumstances where promoting your personal brand is good business and necessary for gaining and maintaining clientele and public trust. But, for those who are in positional authority management—particularly publicly funded or government positions—a delicate balance exists between publicly supporting your organization and generating an appearance, actual or perceived, of external self-gratification over your commitment as a leader to the team you lead. It is in this balance where a leader navigating the current selfie-landscape should ask themselves: Does your existing reputation need self-promotion? If the answer is yes, is focusing your efforts external to your team the best course of action to improve it?

The higher that one rises in their organization the less honest and trusted feedback they receive; no one is telling the emperor they have no clothes. So, where can the well-intended leader find an outlet for self-awareness? In a crowded field of innovative leadership development, which incorporates charismatic and enthusiastic leadership and consulting, there is an often-overlooked leadership laboratory that provides endless guidance without confusing the message with sensationalism: history. Leadership examples provided through the study of history—especially American history—are honest, blunt, inspiring, and sometimes painful, but without an agenda.

We all have an ego, but as history has shown us, effective leaders need a manageable one. Every cell phone has a camera and immediate access to social media. The temptation is ever-present for the modern leader, regardless of career level, to document their own successes. There have been leaders throughout history with massive egos, often to their detriment. However, these historical leaders did not have a camera and a Wi-Fi connection in their back pockets, or britches or gowns, depending on what time in history. Perhaps nineteenth century egocentric leader Napoleon did not commission the famed portrait of himself crossing the Alps, but he could not resist using the image for his own self-promotion. 2 We may never lead an army over the highest mountain range in Europe to conquer the Austrians, but we can learn from historical leaders who have been viewed as putting their own persona above others.

Napoleon may belong to Europe, but Americans are fortunate to live in a country with an endless leadership heritage. It is at historical sites and memorials where the nexus of meaningful, deeply impacting leadership development and history exists. Such sacred places are where pure selfless leadership, exemplified by true sacrifice is memorialized, such as the USS Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor, the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Ground Zero at the World Trade Center site, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery, the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Gettysburg battlefield. It is here, on such hallowed ground, where “selfie leadership” seems foreign, and even obscene.

With countless historical events that provide excellent examples for leadership, the Civil War is unique in American history. Our country literally tore itself apart. One can easily apply the colossal leadership trials of the Civil War to any modern organization during the present-day, volatile environment. There were a multitude of issues converging simultaneously that apply today: race and equality, extraordinary political division, economic concerns, resource allocation challenges, organizational management and mismanagement, interpersonal relationship complexities, and perseverance through insurmountable odds.

The Civil War may seem too complex a topic in which to find practical, present-day leadership lessons, particularly those of individual self-awareness. This is why, of the many case studies of the period, Gettysburg is exceptional. The chaotic, crisis leadership environment created at the Battle of Gettysburg—including the events leading up to the battle—provides an outstanding opportunity to apply historical events to today’s challenging and stressful leadership landscape. Gettysburg is a true crisis leadership laboratory and is frequently used for its leadership lessons within the corporate world, public sector, and the military.

What was once a mechanism to improve business and government management has evolved into a business of its own. “Leadership development” has become nebulous in its definition, application, and practice. Scholars of organizational leadership and management sciences have criticized modern leadership development programs as superficial and ineffective, failing to make a significant, long-term positive impact in today’s—and tomorrow’s—leaders. 3,4 Within this confusing landscape of quick-fix, “one size fits all” leadership development and consulting, is an often overlooked but omnipresent vessel that can provide stoic leadership lessons for improvement and inspiration—history.

ICMA’s Gettysburg Leadership Institute, supported and facilitated by the Gettysburg Foundation, is an example of a leadership development and improvement program utilizing an actual event in American history with the sincere intention of creating ethical, introspective, long-lasting, authentic change within local government leaders for the greater good—and was the inspiration for this article.

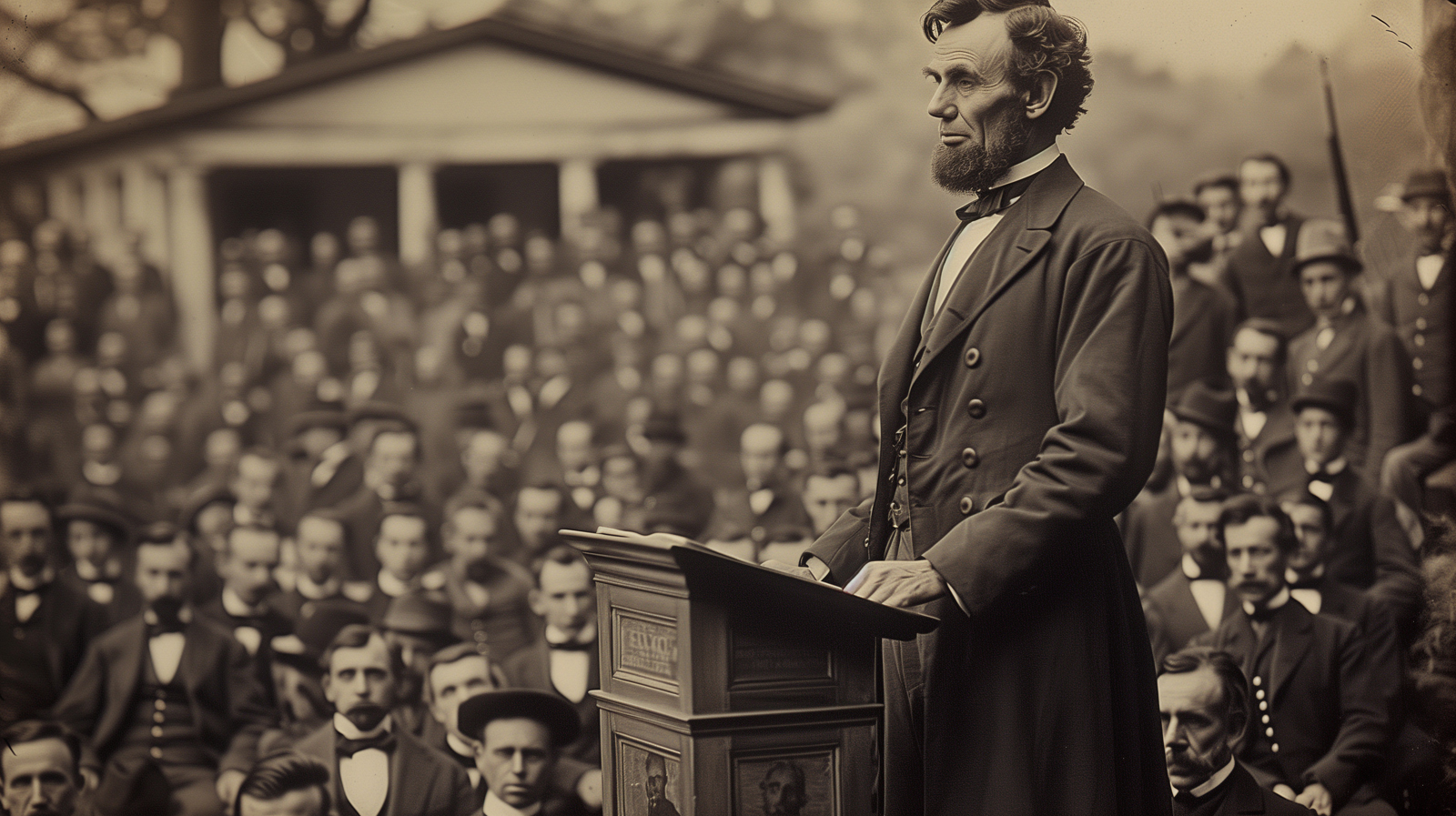

If you need a selfless-leadership example of ethics in the face of pressure, look no further than President Abraham Lincoln’s position leading up to Gettysburg. Tens of thousands of Americans had been killed and there was a growing movement in the North to end the war. 5,6 A loss at Gettysburg could have led to the end of the Union, the preservation of the institution of slavery in the southern states, and possibly its spread in future western states. In 1863, with an election looming a year away, Lincoln was under an unimaginable amount of public and political pressure to end the bloodshed. To compound Lincoln’s already unbelievable situation, he was grief-stricken after the death of his 11-year-old son five months prior, with whom he was extremely close. 7

The Confederacy knew that the Lincoln administration was under this enormous stress, and they sought to capitalize upon it. Two bloody years into the war, the South had won the majority of major combat engagements in the Eastern Theater and was gaining Northern political momentum for their cause: to form a new nation through a peace settlement. However, being outnumbered and under-resourced, in June 1863, the Confederacy sought an audacious opportunity to end the war on their terms by invading the North in Pennsylvania. They had hoped, with a major victory in northern territory, there would be foreign recognition of the Confederacy, and that the Union would either capitulate to a settled peace agreement or that Lincoln would be so politically damaged he would lose the 1864 election, allowing a new rival president to seek peace over the preservation of the Union. 8

Lessons in history can remind the modern leader to prepare for the unexpected. And while the South had begun their bold invasion of the north, neither the Confederate Army of 75,000 soldiers nor the 88,000-strong Union Army expected to clash in the small, picturesque Pennsylvania farming community during the hot summer of 1863. 9 To compound the already dynamic and ambiguous leadership landscape, after two years of replacing numerous ineffective commanding generals, Lincoln named a new commander to take charge of his enormous army just three days before facing the most audacious and successful general of the Confederacy, Robert E. Lee—the very man that Lincoln initially offered command of all federal forces to upon the onset of the war. All of this was occurring while an equally monumental campaign was being waged 1,000 miles to the west of Gettysburg in Vicksburg, Mississippi, by Union General Ulysses S. Grant. 10,11,12,13,14

Over a three-day period, the Civil War’s deadliest single battle unfolded. Union forces prevailed, handing the South arguably their most devastating defeat. While the war raged on for another two years after the battle, Gettysburg is widely recognized as one of the most consequential turning points of the war. It is hard for modern American society to fully comprehend the devastation and loss that occurred. There were more than 51,000 casualties—dead and wounded—and the stakes were never higher for our nation. 15 This single event provides countless examples—both good and bad—of command and control, communication, strategic planning, political influence, individual initiative, stress management, creative thinking, interpersonal conflict, resource management, tactical operations, risk taking, and most of all, selfless leadership and followership.

The Confederate Army never again saw victories—politically or tactically—on the same scale as it did prior to Gettysburg. The battle was impactful enough that five months afterward it became President Lincoln’s inspiration behind one of the most famous speeches in American history, the immortal Gettysburg Address. In that speech, he offered that this nation was “…dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” and that our nation, along with its principals, “…shall have a new birth of freedom,” presumably from the sin of slavery and the roots of division. It is important to remember, almost a year prior to uttering these words, and against significant resistance, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which his political rivals strongly opposed. Furthermore, during this time he was working tirelessly to gain the votes in Congress to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery in our country. 16,17

To be clear, the overwhelming majority of us are not operating in a high-risk, life-or-death leadership environment as presented in Gettysburg. However, leadership in any form is serious business; the business of caring for and influencing people while accomplishing an organizational mission. The examination of our own leadership behaviors through the lens of historical events can be a vehicle for valuable self-evaluation.

A look at pivotal historical events involving ordinary people, who became extraordinary leaders in the moment, allows for both humble self-awareness and encouragement. Encouragement to the modern leader that, whatever the current challenge, someone in history has “been there and done that.” The women and men who set these examples during the seminal events in American history did so under unbelievable odds, in astonishing conditions, and without taking selfies…something that the modern leader, regardless of the industry, might want to consider before making that next social media post.

DOUGLAS NEWMAN is assistant chief of police for Fife, Washington, USA. He is also a retired military officer with a background in expeditionary warfare and leadership.

Endnotes

1 Collins, J. (2016). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap and others don’t. Instaread.

2 First Consul Crossing the Alps via the Great Saint Bernard Pass. (n.d.) Fondation Napoléon, Retrieved June 26, 2024 from https://www.napoleon.org/en/history-of-the-two-empires/images/the-first-consul-crossing-the-alps-via-the-great-saint-bernard-pass/

3 Day, D. V., & Kragt, D. (2023). Leadership Development: Past, Present and Future. The SAGE Handbook of Leadership, 164.

4 Beerel, A. (2021). Rethinking leadership: A critique of contemporary theories. Routledge.

5 Hoke, J. (1887). The Great Tradition of 1863: Or, General Lee in Pennsylvania. WJ Shuey.

6 Weber, J. L. (2011). Lincoln’s Critics: The Copperheads. Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 32(1), 33-47.

7 Burlingame, M. (2017). Abraham Lincoln and the Death of His Son Willie. When Life Strikes the President: Scandal, Death, and Illness in the White House, Oxford University Press.

8 Ibid, 4.

9 Millett, A. R., & Maslowski, P. (1994). For the common defense. Free Press.

10 American Battlefield Trust. (n.d.). Gettysburg. Retrieved June 26, 2024 from https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/gettysburg

11 U.S. Library of Congress. (n.d.). Abraham Lincoln and Emancipation, Retrieved June 26, 2024 from https://www.loc.gov/collections/abraham-lincoln-papers/articles-and-essays/abraham-lincoln-and-emancipation/.

12 McPherson, J. M. (2003). Battle cry of freedom: The Civil War era. Oxford University Press.

13 Ibid, 8.

14 National Parks Service. (n.d.). Hooker takes command. Retrieved June 26, 2024 from https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/hooker-takes-command.htm.

15 American Battlefield Trust. (n.d.). George B. McClellan. Retrieved June 26, 2024 from https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/george-b-mcclellan

16 U.S. Library of Congress. (n.d.). The Civil War in America December 1862–October 1863. Retrieved June 26, 2024 from https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/civil-war-in-america/december-1862-october-1863.html.

17 Ibid, 8.

Additional References

McPherson, J. (2018). To Conquer a Peace: Lee’s Goals in the Gettysburg Campaign. Historynet, Retrieved June 26, 2024 from https://www.historynet.com/conquer-peace-lees-goals-gettysburg-campaign/

Reardon, C. & Vossler, T. (n.d.). The Gettysburg Campaign. Center of Military History United States Army.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!