Local governments have developed their budgets in essentially the same way for decades. The essence of the traditional approach is, first, that the budget is incremental. This means that last year’s budget becomes next year’s budget with changes at the margin. Second, the budget is built around line items—categories of spending like personnel, commodities, and contractual services, which are then grouped into departments and funds. This approach has been criticized for almost as long as it has been in use in local governments.

One of the most prominent criticisms is that past decisions are frozen in place past the point at which they are affordable or relevant. Once a change is made to the budget, the change is carried over to successive budgets. Let’s illustrate: if a department gets a grant from, say, state or federal government to increase staffing for a few years, those positions come to be regarded as part of the department’s baseline budget. Once the grant ends, the expenditure continues to be funded without an evaluation of whether those positions are creating sufficient value for the community to justify the cost. This “layering on” effect contributes to financial distress and is a suboptimal allocation of resources.

Another criticism is that the traditional budget is not strategic. Spending is allocated to line items that concern the day-to-day operations of government. Line items like “travel,” “supplies,” or “miscellaneous” don’t speak to how spending impacts big-picture results like public safety, mobility, health, etc. Also, historical precedent is the primary determinant of how much money is allocated to each line item. This is backward-looking, not forward-looking. All of this means that the budget process is not well suited to handle big-picture and/or emerging issues.

A final criticism is that traditional budgeting is a “zero-sum game.” This means that for one party to win, someone else must lose. For one department to get more funding, another department must get less. In traditional budgeting, this is seen as a win for one department and a loss for the other. A zero-sum game promotes power dynamics that favor maintaining the status quo and encourages self-interested decision making.

These criticisms have led to attempts to do budgeting better. Two widely recognized innovations are zero-base budgeting and priority-based budgeting. A number of intrepid local governments have tried these methods with varying degrees of success and staying power. Among the majority of local governments, however, the traditional budget has endured…and for good reasons. It is simple, the results are predictable, line items provide a sense of control, incrementalism avoids radical change, and it is flexible—since there is no overarching strategic direction, public officials can more easily declare new policies when then they want.

If prior efforts at new ways of budgeting have met with limited success and the traditional budget has important advantages, why have we written this article and why are you reading it? The contention of the Rethinking Budgeting initiative—a collaboration between ICMA, GFOA, and the NLC—is that there are three new forces that make the traditional budget less tenable than in the past. However, it is not all downside. After we examine these threats, we’ll explore the opportunities that work in favor of local governments.

Three Threats to the Status Quo

1. Stagnant or Diminishing Resources

The first threat is stagnant or diminishing resources available to local governments. Much of the traditional budget’s success rests on distributing budget increases to enough stakeholders to maintain a stable governing coalition. However, the traditional budget does not have a good answer to resource declines. This is why we see across-the-board cuts as a common response to fiscal distress: everyone is cut evenly. However, this does not optimally size or shape government to the conditions it faces. In this issue of PM magazine, we have an article on “Rethinking Revenue” that delves into revenue reform. But, it is also important that government spending plans be more adaptable to resource-constrained environments.

2. Conflict

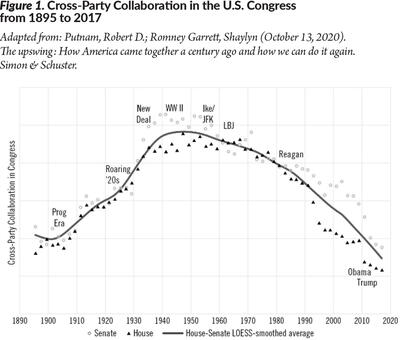

Conflict is the second threat. The defining conflict of our times is political polarization. Figure 1 shows cross-party collaboration in the United States Congress from 1895 to 2017. We see today that cross-party collaboration has reached all-time lows. Political conflict is not limited to federal government officials. It affects the general public, too. Conflict has gone along with declining trust. Surveys show that in the early 1960s, nearly two-thirds of Americans trusted other people, but by the 2020s only one-third did.1 The traditional budget lessens conflict by relying on historical precedent. However, in an environment of markedly lower trust, where many people no longer believe that others have their best interests in mind, people may not be willing to accept historical precedent as a justification for how resources are distributed.

3. Volatility

The third threat is volatility. Perhaps the most important source of volatility is information. The amount of information—and access to it—has been increasing exponentially over the past few decades. This phenomenon seems to have reached a threshold point, where new ideas can rapidly spread to a point where they are adopted by a critical mass of people. The result is rapid changes in public opinion and consequent demands on institutions. For instance, the role of social media in catalyzing social unrest and coordinating protest organizations has been well documented.2 This volatility challenges the legitimacy of all established organizations.

The traditional budget is unsuited to provide legitimacy in this volatile environment.3 First, the traditional budget relies on historical precedent for much of its legitimacy. New information and ideas, by definition, do not defer to historical precedent. Second, the traditional budget does not have a good means for getting feedback from an environment that is subject to rapid change, much less a means for changing if and when the need to do so is identified.

Opportunities for Better Budgeting

The Rethinking Budgeting initiative has identified opportunities for local governments to budget better. The initiative is still in its early phases, so there will be much more to come. For this article, we’ll introduce key concepts that are foundational to rethinking how we do budgeting.

Modern Behavioral Science Offers New Insights into How We Make Decisions

Behavioral scientists study how we—human beings—interact with each other and our environment in ways that impact our preferences, decisions, and behaviors. We can use this knowledge to design better processes and achieve better outcomes for your organization and the community. As a simple example, there is an underlying assumption in budgeting that people are rational—show them the numbers and they will make the right decision. However, behavioral science tells us that people are “predictably irrational.” They will interpret numbers and make choices in ways we might not expect.

Let’s take an example that is an integral part of budgeting: choosing between options. From a purely rational standpoint, the more options you have, the better! However, research has shown that under conditions like those that often exist in budgeting, more options can work against good decision making. This is called “choice overload” and is characterized by long delays in making a decision, not making a decision at all, and frustration. Knowing this allows the budget officer to mitigate choice overload. The most obvious way is to present decision makers with fewer choices. Decision makers will often appreciate being provided with a smaller number of solid choices that they can become familiar with rather than a wide range of options. For example, GFOA has observed that managers have success by presenting decision makers with a limited menu of carefully formed strategies to close a budget deficit. Decision makers still have a choice but don’t feel overwhelmed by too many choices.

That is, of course, but one tactic for one common decision-making problem. The larger message is that the budget officer should be thought of as a “choice architect.” Choices can’t help but to have an architecture, such as large number of choices versus a limited number. The architecture influences how choices are made—like how the architecture of a physical space will influence how people use that space. The budget officer must: (1) be aware of how the presentation of information influences choice, and (2) use professional judgment to apply choice architecture wisely. Check out the Rethinking Budgeting’s series on “Using Behavioral Science for Better Decision-Making” to go deeper on this topic.

Key Questions to Ask: Do you understand how the process and decision-making environment that you’ve set up for the budget encourages or discourages good decision making? What can you do to architect a better decision-making environment?

Understand What’s “Fair” and the Implications for Budgeting

Conflict is a defining feature of today’s political environment. Issues of fairness are often at the heart of the conflict. The conventional budget decreases or avoids conflict by relying on historical precedent, but many people are not willing to defer to historical precedent today. Local governments need a more comprehensive understanding of “fairness” because more attention to fairness in the budget could play a role in positively influencing some of the most important potential conflicts of our time.

Fairness is a multi-faceted concept. Understanding all facets allows the budget process to be designed so that the most people feel fairly treated. A limited understanding, at best, leaves opportunities unrealized and, at worst, risks more conflict with those that feel unfairly treated. We’ll examine two major facets in this article, but you can dive deeper into the concept of fairness in the Rethinking Budgeting’s “What’s Fair” series.

Procedural Justice. The first facet of fairness is procedural justice, which refers to a fair process. Do people have the chance for input? Is the information used to make decisions seen as accurate? Are clear decision-making criteria applied equally to everyone? Procedural justice is critical because people are more willing to accept a decision that is not consistent with their self-interest if they feel the process used to reach the decision was fair. This has been shown in applications as disparate as courtrooms and corporate strategic planning. GFOA has observed that it is no less valid in budgeting. There will never be enough resources for everyone to get everything they want. We have observed again and again that budget processes that exhibit procedural justice are far better at navigating conflict.

Distributive Justice. The second facet of fairness is distributive justice. The simplest definition is that people get what they deserve. Of course, what people “deserve” is open to interpretation! To illustrate, many local governments are grappling with “equity” in budgeting. “Equity” means people should be treated differently by public policy to compensate for different circumstances and consequent need for help from government. It is often associated with equality of outcomes. However, this is not the only interpretation of what is “deserved.” “Proportionality” means that people are given resources commensurate with their contributions. It is more closely associated with equality of opportunity. Nearly everyone believes in a mix of proportionality and equity, but equity tends to be favored by political liberals, while proportionality appeals to everyone but more so for conservatives. This means budget officers will need to think about how and where the equity principle might be operative in budgeting and where the proportionality principle might hold sway. Because most people believe in a mix of both and because a lot of conflict hinges on which definition is used and when local governments must be intentional about how they are applied. Also, this is not always an either/or proposition. There may be opportunities to satisfy both with clever approaches to public policy.

Key Questions to Ask: Does your budget process exhibit the features of procedural justice? Where might it be important to apply the principle of equity and where might it be important to apply proportionality? Where might it be important and possible to apply both?

Avoid the Accountability Trap

Local governments are being asked to deal with complex and difficult problems, like drug abuse, climate change, social inequalities, and more. Given the high stakes of the issues and the potentially large sums of money needed to address them, there can be a justifiable interest that the government (and its staff) be held “accountable.” This sounds fine, in theory, but there are some practical problems with a focus on accountability. Wharton organizational psychologist Adam Grant points out that focusing on only accountability raises anxiety and impedes communication. What is the solution? To be clear, we are not anti-accountability. As ancient wisdom prescribes, balance in all things. What balances with accountability? Psychological safety.

Psychological safety is a shared belief, held by members of a team, that the group is a safe place for taking risks. It is a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject, or punish someone for speaking up. It describes a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect.4 Psychological safety is necessary for challenging deeply held beliefs and assumptions and taken-for-granted ways of operating. To illustrate the importance of psychological safety, consider the experience of software giant Google. Google wanted to know what makes for a successful, innovative team. After a two-year study covering 280 teams, Google found only one difference between teams that were innovative and teams that were not: psychological safety.5

You can check out Rethinking Revenue’s “The Accountability Trap” to go deeper into how to create psychological safety and integrate it with accountability. In this article, we’ll limit ourselves to the first and most important point: differentiate between two kinds of accountability. Those are accountability for results and accountability for process. It is common to think that decisive leadership “demands results” or that we should “budget for results.” However, an over-emphasis on results meant that no one wants to be seen as failing to deliver results, admitting that they don’t have the answer, or questioning processes that have delivered results in the past. Process accountability, conversely, asks us to evaluate how we get to the results and learn how to do it better.

To illustrate, let’s consider King County, Washington. The county focuses its accountability on measures of the process used to meet a goal. Within a given budget cycle, the county can change the process based on feedback from its measures. The larger goal or outcome might be to reduce homelessness, but accountability during the budget cycle is centered around the actions and milestones required to meet the goal.

Ultimately, balancing accountability and psychological safety is about building a learning culture where ideas that don’t work (which will be many when trying to address complex community challenges) are used to bring local government closer to ideas that will work and building a budget that reflects those lessons.

Key Questions to Ask: How psychologically safe is your organization? Do people really feel free to offer up their best thinking? What can you do to improve psychological safety? Might an overemphasis on results accountability and under-emphasis on process accountability be an imbalance in your organization that you can correct?

Conclusion

Local governments have both an imperative and an opportunity to rethink how they do budgeting. A rethought budgeting process can better direct resources to where they will do the most good. It also will help local governments better navigate resource constraints, conflict, and a volatile environment. The Rethinking Budgeting initiative will continue progress and if you’d like to be a part of it or just kept apprised of progress, please let us know at https://www.gfoa.org/rtb-updates.

SHAYNE KAVANAGH is the senior manager of research for the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA).

SABINA AGARUNOVA, CPA, is the chief financial officer of the International City/County Management Association (ICMA).

Endnotes

1 Putnam, Robert D.; Romney Garrett, Shaylyn (October 13, 2020). The upswing: How America came together a century ago and how we can do it again. Simon & Schuster.

2 Tufekci, Zeynep (2017). Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest. Yale University Press.

3 Inspired by: Gurri, Martin (2018). The revolt of the public and the crisis of authority in the new millennium. Stripe Press.

4 Edmondson, Amy C. “Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams.” Administrative Science Quarterly 44 (2): 350–83. 1999. Taken from: Duhigg, Charles. Smarter faster better: The transformative power of real productivity. Random House Publishing Group. 2016.

5 “This is the way Google and IDEO foster creativity.” An undated podcast in the IDEOU “Creative Confidence” podcast series, featuring, Frederik Pferdt, chief innovation evangelist at Google.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!