On November 19, 2013, former ICMA President Sylvester “Sy” Murray was interviewed by staff in Washington, D.C. What resulted was a fascinating collection of reminisces from one of the earliest African-American city managers in the profession. The article published here was excerpted and edited from that November 2013 interview.

ICMA: How did you get started in professional local government management?

SM: I was born and raised in Miami, Florida, and Miami had had the council-manager form of government for a long time. I wasn’t aware of this until I went to college at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. Stephen Sweeney, founder and dean of the Fels Institute of Government at the University of Pennsylvania, served on Lincoln’s board of trustees.

In those days, there were two schools that were well known for producing city managers: the University of Kansas and the Fels Institute. In my senior year, Stephen Sweeney, of Fels, came to me and asked what me what I wanted to do with my life. I told him my ambition was to become a lawyer so that I could go back to Miami, become the mayor, and do things for my people.

He said, “Are you aware that Miami operates with a council-manager form of government?” I said, “No. So what?” And he said, “Well, the mayor doesn’t do things in Miami. That’s a person called a city manager.”

He went on to say, “The advantage of being the city manager is that people select you based on whether you are qualified to be city manager. The mayor has to convince people that he is qualified.

“If you really want to go back and run the city of Miami, you need to go into city management. Come to my school.” And that’s how I got into the profession.

ICMA: Did you have other mentors along the way?

SM: Oh yes. I’ve had a number of them. Fels required students to have an internship, and the internship had to be with a city manager, but it could be located almost anywhere. So when it came time for me to get an internship, the school said, “We have an internship for you in a community near Philadelphia.”

I responded by asking, “But why? I’m from Miami. I now know it has the council-manager form of government, so I’d like to do my internship in Miami.” The response was, “Well, I don’t think that you can do it.” I said, “Why not?” And they said, “You won’t be accepted. We’ve already tried it.”

I said, “Well, that doesn’t sound right. So let me go and try it. Who is it that you talked to?”

Fels staff had talked to the assistant city manager in Miami, and I went to see him and explained that I wanted an internship with him. And he said they couldn’t do it. I was insistent, but he said no.

I told him, “My family’s here, I was raised here, I finished high school here, and I want to serve an internship here.” He told me to come back the next day.

So I went back, and it was obvious that he had talked with the city manager at that time and maybe even looked up my family history to see how long I’d lived in Miami, and his response to me was, “We’re not going to give you an internship in the city manager’s office, but we will give you an internship at the recreation department in the black neighborhood.” This was in the early 1960s.

My response was, “No. That’s not acceptable. I went to the same school that you went to. I got the same degree as you. Did you serve an internship in the recreation department?” He didn’t respond. I said, “No, you didn’t. So I don’t want an internship in the recreation department,” and he told me, “Well, you make your decision.” So I left.

When I went back to Fels, I told the dean “I agree with you now. I can’t do my internship in Miami,” and he said, “While you were in Florida, we found another city for you.” That was the city of Daytona Beach. Another graduate of Fels—his name was Norman Hickey—accepted me willingly and gave me extremely good guidance.

ICMA: Tell us a little more about him.

SM: Norman Hickey was a religious man from the Midwest. He said, “We’re going to give you this internship, and we really want you to do well and work with us.” I said, “Okay, I’ll really do my best.”

So there I was—in the front of the city manager’s office—and I was the only black man in city hall other than the janitor, who became a good friend of mine. But things generally went well.

ICMA: Run us through your career.

SM: I went to graduate school right after I earned my bachelor’s degree. But this was in the 1960s, when we had the draft, and I was drafted to go into the army. You could be deferred if you were in school, so that was another reason I got into a master’s program. I still finished before I was 25 or 26 years old or whatever age it was that you could be drafted.

After my internship in Florida—at the end of the six months—Norm Hickey offered to hire me. He had an assistant city manager already, so he was going to hire me to be an administrative assistant or management aide.

And then I got my draft notice, and Norm said, “Don’t worry. We’ll get you out of this. But, I told him no. “If my career is to be a city manager, chances are I need to serve in the military.”

Back in those days, you didn’t get to be city manager, or president for that matter, if you hadn’t serve in the military, particularly if you had been drafted. So I decided to go, and I was assured that my Daytona Beach job would be waiting for me when I came back.

My captain kept promoting me, and I kept helping people. The lieutenant colonel, who was the battalion commander, asked me to come to his office and volunteer to go to officer’s training school. He said I was obviously a leader of men, and that I should go to officer’s training school and let the Army be my career.

I told him I wanted to become a city manager. He said, “Let me tell you two things. Number one, if you’re an officer in the military, you can be a city manager because during times of war, wherever we are located, our bases become like cities. So you can still be a manager and manage the base. Number two, no American city is going to hire you as its manager, so go to officer’s training school.”

My response to him was, “No thank you. I want to become a city manager of a city and not of a military base.” So I left the Army after two years and went back to Daytona Beach, got promoted, and eventually became director of the city planning and building department and did well there.

After two years, I sent out applications to become an assistant city manager because I wanted to move up. I received a letter from a man in an Illinois community who accepted everything about me on paper. He said, “We want to hire you. Please send us a picture so that when you come up for the onsite interview, we can share it with the newspapers.” So I sent the picture, and I never heard from him again.

Then I was hired over the phone by a man in Oklahoma who sent me a ticket to fly out and participate in a personal interview. He came to the airport to pick me up when I arrived, and I went up to him because he obviously didn’t know who I was.

He looked at me and said, “You’re Sy Murray?” I said, “Yes, I’m Sy Murray.” He said, “Mr. Murray, I’m going to have to put you back on the plane. The city council will not accept you. If I hire you, they will fire me.”

Eventually, I got an assistant city manager’s job in Richland, Washington. I moved from Daytona Beach with my wife and kids, and the transition worked out beautifully. I was there for about two years, and then I was asked to come to the city of Inkster, Michigan, to interview for what would become my first city manager’s job.

I served Inkster for three years, and then I was invited to interview for a position with Ann Arbor, Michigan. I got the city manager’s job in Ann Arbor, where I stayed for six years until Cincinnati, Ohio, asked me to interview for the city manager’s job in that community. I was hired there and stayed for six years.

For each of my city manager jobs—and there were four of them—I was asked to apply, which made me feel really good. It was just like my mentor at Fels had told me: “You can run a city and somebody will ask you to come do it. You don’t have to go out and be elected.”

ICMA: Compare the demographics of local government managers today with those of past years.

SM: Blacks became managers, in the most part, after the 1970s, when we also became mayors and city councilmembers. During the ‘70s and after the riots that followed Martin Luther King’s shooting, it was popular to be liberal, and the councils and mayors were mostly white and many hired black city managers.

But after the 1970s and into the 1980s, whites began moving out of the cities into the suburbs—interstate highways facilitated that movement—and blacks became mayors and councilmembers, who subsequently hired blacks to serve as managers. So a considerable number of black city managers were hired because blacks were doing the hiring.

ICMA: Tell me how you got involved with ICMA.

SM: I got involved through the Fels Institute. Most city managers then either went to Fels or to Kansas. If you went to Fels, you became a member of ICMA automatically as part of your training. The deans of the schools often were involved with ICMA. So that’s how I got involved, by attending Fels.

ICMA: Did ICMA help you with your career and other various issues along the way?

SM: Yes, especially when I ran for ICMA office. You know, I was city manager of Cincinnati at the same time I ran ICMA’s “council”—the executive board—and that was because the ICMA executive director and others encouraged me to run for president. They paved the way for me, so ICMA has been very much a positive part of my career.

ICMA: What was it like being a minority in a majority white profession?

SM: It was not the best situation. Back in the day, ICMA elections were based on a nominating process, and the person nominated through the nominating committee, invariably, was voted in as president.

The first year I was nominated by the committee, a write-in candidate won. He said it was his turn, and that he should have been nominated. [I interpreted his remarks to imply] that a black city manager wasn’t needed as president of the profession at that time.

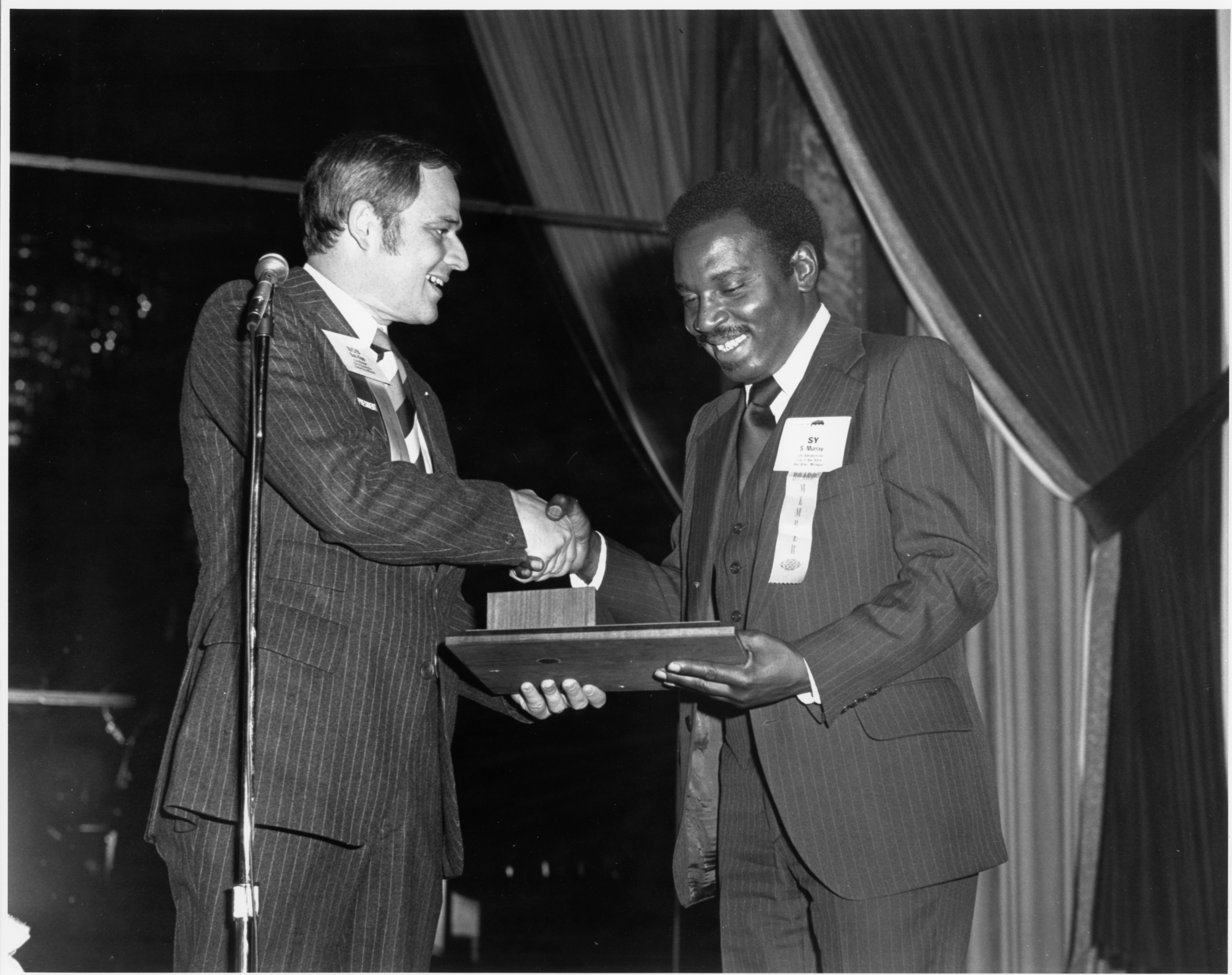

The next year, I was nominated again and won. So that’s how I became ICMA’s first black president.

ICMA: Tell me about your teaching career.

SM: I was fired at my last city manager’s job in San Diego, and it was a pretty contentious situation. At the time, San Diego was the largest city in the country that had the council-manager form of government, so I felt I had reached the top, if only for a short period of time.

And then when it became obvious that I was going to be fired, I received phone calls from cities asking me to apply to be their manager. But I just didn’t feel good about city management.

I also received a phone call from Coopers & Lybrand, which at the time was a Big Eight CPA firm, asking if I would work for the firm as a consultant and be placed on a track to eventually become a non-CPA partner. So rather than interviewing to become a city manager again, I accepted the Coopers & Lybrand offer. It was Coopers & Lybrand that brought me back to Ohio.

After several years with the firm and turning down a promotion that would have involved relocating to Detroit, I received a call from Cleveland State University. The dean said he wanted me to come and help build up the university’s city management program. He offered me the right amount of money and the right faculty position.

I began teaching there as an associate professor, tenure track, at a very good salary. That’s how I got involved in teaching. I spent 18 years at Cleveland State University and moved up from associate professor to full professor and to coordinator of the public management program.

We graduated a lot of students who went into city management. After 18 years I retired from that, bought a farm in Georgia, and thought I was going there to retire permanently. My farm was located close to two schools that offer public administration programs—Georgia Southern and Savannah State. Both schools asked if I would adjunct with them.

The adjunct at Savannah State turned out to be a full-time job, so I stayed there for four-and-a-half years. Eventually I found a new professor for the program and went back to the farm. After six months at the farm, I got a call from Jackson State in Mississippi, where they asked me to help them for just a year.And that’s where I am now.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!