By Valmarie Turner and David Street

Many of the issues we face from day to day in local government are ambiguous and refuse to adhere to our jurisdictional boundaries. As professionals, we’re expected to wade into such circumstances with confidence and emerge with demonstrable results. We often meet this expectation, but when issues arise at the intersection of professional adversity and human suffering, a collaborative, inclusive, multijurisdictional, and multitiered process can make all the difference.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness indicates that approximately 2 million people with mental illness are booked into jails each year, and nearly 15 percent of the men and 30 percent of the women have a serious mental health condition.1 The further entry of people with serious mental illness into the criminal justice system is a concern not only nationally but locally. In FY 2017, Loudoun County’s Department of Mental Health, Substance Abuse, and Developmental Services provided treatment to more than 300 people in the county’s adult detention center.

As with any complex issue, solutions are often multifaceted and require a “many tools in the toolbox” approach. One important tool that Loudoun implemented is a special docket in the Loudoun County General District Court. The mental health docket, as implemented in Loudoun, is a docket complemented by a structured post-plea program designed to provide direct support for defendants diagnosed with serious mental illness. Its mission is to provide coordination between the mental health and criminal justice communities to reduce recidivism, improve public safety, and support people with serious mental illness.

This is accomplished by developing individualized, comprehensive, community-based treatment plans reinforced by court supervision. While mental health dockets (also commonly referred to as behavioral health dockets) have been implemented in 10 courts across eight jurisdictions in Virginia, Loudoun’s development process is noteworthy due to the high level of collaboration between public and nonprofit organizations, elected and appointed officials, and professional county staff.

Recognizing Needs

The origins of Loudoun’s mental health docket date back to 2013, when approximately 30 representatives of Loudoun’s human, social, and criminal justice communities engaged in a two-day facilitated cross-systems mapping exercise that used the Sequential Intercept Model2 to map how people interacted with both mental health services and the criminal justice system. The model identified five intercepts: 1) law enforcement and emergency services, 2) initial detention and initial court hearings, 3) jails and courts, 4) reentry, and 5) community corrections and community support.

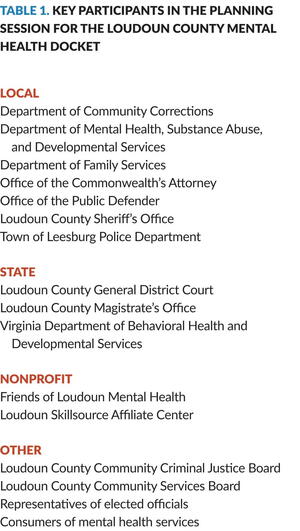

The planning session itself is a milestone in that it placed a critical mass of the “right” representatives of the “right” organizations in a room together in a structured environment. The group, which included a number of stakeholder organizations (some of which are listed in Table 1), was facilitated by Virginia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services through a grant.

In the mapping process, attendees followed the path of a person through the criminal justice system. What the group found was that people with serious mental illness ended up being funneled through the system with everyone else receiving a fine, jail sentence, or probation with no firm requirement or plan for treatment of the underlying mental health issue. The map showed that a lack of focus on the needs of the individual contributed to the perpetuation of a cycle in which a mental health crisis leads to crime, then crime leads to interactions with law enforcement and, ultimately, to further entry into the criminal justice system. In short, people were not accessing mental health services once released from custody. The county’s performance metrics bear this out: Of the 300 inmates who accessed treatment in the adult detention center, fewer than 40, or approximately 12 percent, continued into community-based treatment upon release.

Building the Team and Planning the Docket

Two main factors kick-started the course charted by Loudoun’s cross-systems mapping exercise.

The first was the existence of a state-level cross-systems mapping initiative that began in 2008 and supported local mapping exercises like the one in which Loudoun engaged. The statewide focus on and support of the mapping exercise permitted Loudoun’s criminal justice and human services communities to see the extent to which the system was being impacted by persons with serious mental health issues. So the group decided to make changes. For example, Loudoun successfully leveraged training and additional state resources to build on the work already accomplished at the state level and in other jurisdictions across Virginia.

The second was the existence of an active and engaged stakeholder organization, the Loudoun County Community Criminal Justice Board (CCJB), a 19-member board made up of members mandated by state code and members appointed by Loudoun County’s Board of Supervisors.

The discussions held at the CCJB level resulted in the establishment of a subcommittee to complete a feasibility study on the implementation of a mental health docket in the county. The CCJB and subcommittee both included subject-matter experts who were able to communicate effectively with criminal justice/law enforcement professionals and mental health care providers, thereby facilitating multijurisdictional and multidepartmental collaboration. The Loudoun County General District Court strongly supported the creation of the docket, and the Department of Community Corrections; the Department of Mental Health, Substance Abuse, and Developmental Services; the Office of the Commonwealth’s Attorney; and the Office of the Public Defender worked together to advocate and plan for its implementation.

Loudoun’s human, social, and criminal justice communities made a critical choice early in the planning process: to focus on the needs of the individual. That decision was reached, in part, because of the participation of key stakeholders in the cross-systems mapping session and their ongoing support and engagement as the planning process for the docket progressed.

Over the course of 2015–16, the subcommittee embarked on a research and development planning process that involved a wide variety of tasks. The subcommittee reviewed and developed administrative procedures and processes, researched models the docket could follow (pre- or post-plea, for example), attended highly specialized training, and visited other jurisdictions in Virginia with established dockets. During these visits, they observed courts, met with judges and local stakeholders, and observed participants in the docket process, as well as the staff supporting the docket. The team found the jurisdiction visits particularly informative, as they allowed the team to incorporate best practices from throughout Virginia into a model that would best meet the needs of Loudoun’s community.

Adapting to Challenges

Plans rarely go unchallenged. It wasn’t until late 2016 that the Supreme Court of Virginia established standards for mental health dockets. The lack of standardization before the court acted left jurisdictions to implement these types of dockets in a variety of different ways. A major concern of Loudoun’s implementation team was the potential for the county to design and implement a program that could be out of compliance with standards the Virginia Supreme Court might eventually adopt. Fortunately, the conversation surrounding mental health and the criminal justice system was amplified across Virginia by ongoing state and local mental health initiatives, which contributed to the creation of the Supreme Court’s standards concurrently with Loudoun County developing its program.

While much of the training and research for the docket was supported by grant funding, it was implemented with existing resources. Originally, the team hoped to receive an implementation grant to accommodate the additional work required by the docket. However, the team did not receive the grant and had no dedicated funding from the county or other sources to implement the program. Instead of delaying or canceling implementation, the team decided to move forward with a limited initiative that could accommodate 10 participants in the first year, hoping that early success would demonstrate the docket’s effectiveness, thereby making it a stronger candidate for future funding.

Funding wasn’t the only resource issue at hand: All departments, organizations, and agencies involved had to prioritize the docket and its potential participants, sometimes at the expense of other priorities. For example, the district court judges cleared time on the court schedule to accommodate the docket. One of the judges is the presiding judge of the docket and the other judges assume the non-specialty cases of the presiding judge while cases on the docket are being addressed.

Gauging Success and Looking Forward

In the nine months since its launch, all but one of the mental health docket’s participants are compliant with their plea agreements and treatment plans. In the short term, that gives the docket a 90 percent success rate; however, the program team and supporting departments are well aware that success is defined along a spectrum and must be evaluated just as the need for care is: on the individual level.

In some cases, success means a participant won’t be rearrested because the docket team had the opportunity to intervene before or during a crisis. In other cases, success means a participant adheres to a long-term illness management and recovery plan and reintegrates with the community through volunteer work, skill development, or permanent employment.

As limited as 10 participants may seem, the positive results of the program have already contributed to additional support and resources. In fact, in the development of the FY 2020 county budget, dedicated funding was approved for several positions supporting the docket, including a clinician and a case manager, which will allow the mental health docket to expand from 10 to 25 participants. As the docket develops a longer track record, the county expects to conduct a recidivism study to evaluate its long-term effectiveness in keeping people in treatment and out of the criminal justice system.

The mental health docket is successful because the state, county, and nonprofit communities worked tirelessly to advocate for, develop, and implement the program. The support and perspective that each stakeholder group provided was invaluable to recognizing and acknowledging need, facilitating cross-jurisdictional communication and collaboration, and adapting to challenges.

Making the docket a reality provides those affected with access to mental health services, often for the first time, and builds a support network that follows them into the community. The docket team, comprised of several of the same agencies that participated in the initial cross-mapping exercise, continues to benefit from the collaborative groundwork that was laid in 2013.

Endnotes

1 Jailing People with Mental Illness (https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Public-Policy/Jailing-People-with-Mental-Illness)

2 The Sequential Intercept Model (https://www.prainc.com/sim/)

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!