By Vince DiMaggio

As local government managers, all of us at one point or another probably have studied myriad public management theories. From scientific management, through Gulick’s rather unruly acronym of POSDSCORB (Planning, Organizing, Staffing, Directing, Coordinating, Reporting, and Budgeting), to Barnard’s authority theory and the need to be both effective and efficient, to the more modern “neo-managerialism” where politics are used to achieve goals, we, as public administrators, have examined, studied, and perhaps written about the strengths and weaknesses of these various schools of thought.

It is a virtual certainty, however, that our daily lives as administrators are not governed by a strict—or even casual—adherence to any one of these management philosophies, nor should they be.

Instead, our individual management styles are most likely formed, for better or worse, from our experiences working for other managers earlier in our careers. In my case, I worked under the venerable Dave Mora, a former ICMA president, during his tenure as the city manager of Salinas, California. This experience shaped my own style of city management.

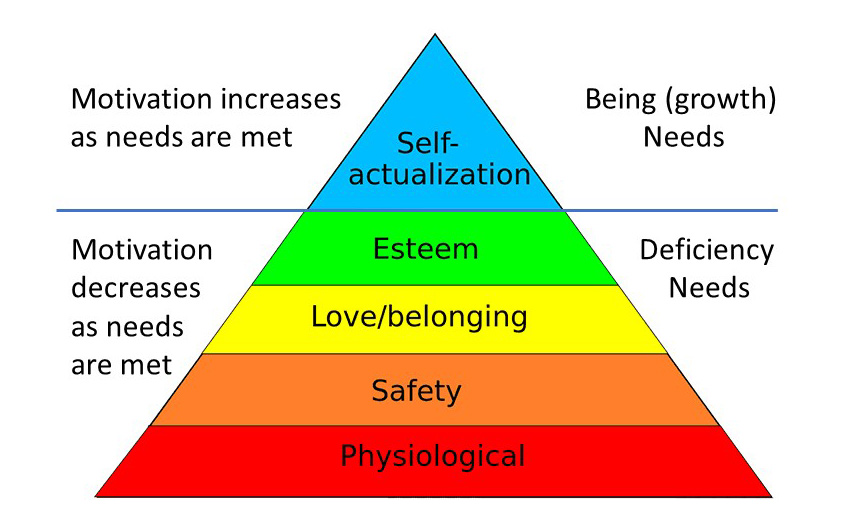

Despite the vast array of scholarship around public administration management theories, it is perhaps ironic that the theory that could potentially benefit managers the most is from the world of psychology: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (see Figure 1).

For managers, we should use maslow’s hierarchy as a guide for inspiring and challenging skilled directors to greater achievement.

Figure 1. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

A Sense of Accomplishment

Maslow’s hierarchy is a theory of motivation. If managers can understand how their actions affect where an assistant or aide sits on Maslow’s hierarchy, they stand an excellent chance at successfully implementing the specific programmatic initiatives that accomplish the political goals and objectives set for them by governing officials.

Administrators, for example, who see a constant need to inject themselves into the minutiae of every step of a program assigned to one of the department directors will, in all likelihood, prevent that department director from achieving any sense of accomplishment in the task.

This will adversely affect his or her ability to manage and attain efficiency in the department’s overall goals and objectives. The result is a stagnation for that department director at Maslow’s level three. The director will constantly struggle with the psychological question of “belonging” and appreciation within the organization, along with introducing imperceptible self-doubt into the person’s mindset.

Conversely, a manager who allows a department director or assistant to assume the reins of a major administrative initiative vital to the organization’s operation or political objective is, in essence, challenging the person to strive to successfully accomplish the goal.

Psychologically, the director benefits from being trusted, reaffirming his or her status within the organization to both internal and external clients.

Nurturing Confidence

I have experienced firsthand that when I have steadily increased responsibilities for department directors, while simultaneously allowing them to define their own path at accomplishing a given objective, then directors’ confidence in their abilities and performance in the job have dramatically increased.

It is also true that members of the department view the director with increased status and esteem and are more likely to agree with direction given to them.

The fact that managers’ fortunes rise or fall based, at least in part, upon the accomplishment of various objectives (political and otherwise) in the organization is often the primary reason for reluctance at assigning greater independent responsibility to the corps of department directors.

I’m not advocating for an abdication of oversight by managers. But, if we start with the basic and necessary assumption that our department directors are capable, credentialed professionals in their field, we must then be completely confident and comfortable with their abilities at taking on more complex projects, with greater independence, that move the organization in the direction that we’ve been charged with guiding it. Maslow’s highest point on the hierarchy is “self-actualization,” and he described it as the fulfillment of the highest needs and attainment of one’s full potential. As to whether this is actually possible, I will leave that argument to the psychological community.

Cultivating Organizational Trust

For managers, we should use Maslow’s hierarchy as a guide for inspiring and challenging skilled directors to greater achievement. By doing so, we cultivate organizational trust between that position and the manager, enhance the self-esteem of the department director, and strengthen the positive perception of the department director by both the employees who are not leaders and the public. We also challenge ourselves to relinquish micromanagement tendencies, thereby increasing our own self-awareness as managers and moving one step closer to self-actualization.

Assistant city manager, El Cajon, California (VdiMaggio@cityofelcajon.us).

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!