By Dale Neef

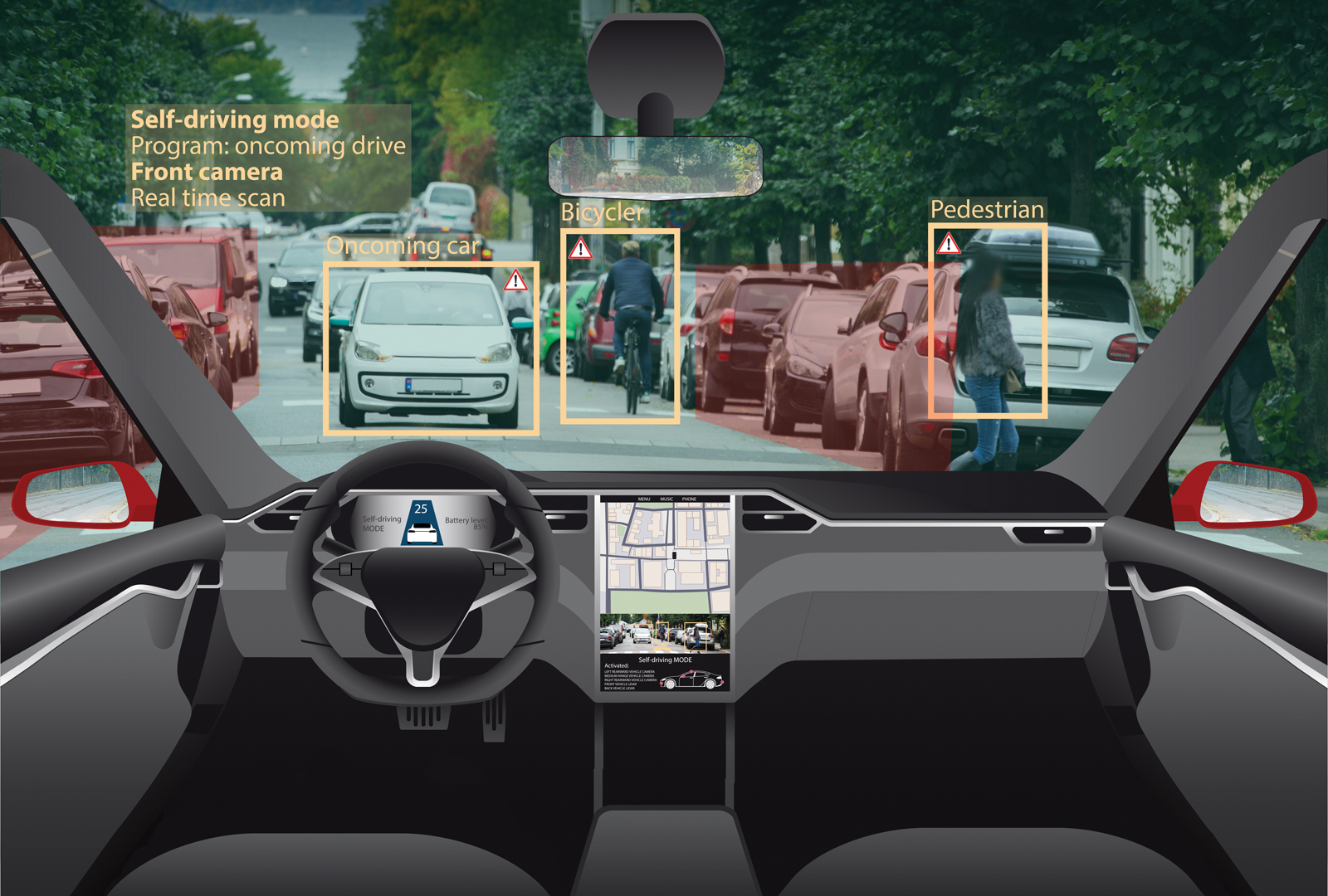

Despite setbacks, including an Uber SUV operating in self-driving mode striking and killing a pedestrian in March 2018, big tech, ride-hailing groups, and the auto industry are all pushing ahead with electrification and shared autonomous vehicles (AVs) faster and with more success than many anticipated.

That means that local government administrators, policymakers, and planners are going to have to start preparing now for the infrastructure and policy changes that this transformational new economy will bring.

With estimates now suggesting that by 2030 some 60 percent of cars on American highways will be self-driving, local governments are starting to take notice, because even if much of the infrastructure necessary for autonomous vehicles and electrified cars can be provided by private sources, AVs will still be driving on state and locally provisioned roads, and will require planning, zoning, permits, and supervision by local government managers and agencies.

Localities themselves will be responsible for improving street signs, ensuring accurate lineage, and creating safe pedestrian zones. And as the conversion to electric engines continues, local government policymakers and administrators will need to provide oversight on a considerable investment in charging stations and other wayside infrastructure—all tied to the electrical grid and coordinated through government and regulatory agencies.

Will these changes to infrastructure be publicly or privately funded, and if through government revenues, where will the money come from? More importantly, how can local government agencies justify funding new infrastructure for a transformational technology that may compete with public transit and significantly reduce municipal revenues?

The Race Is On

The most obvious indication of something big brewing is the near-universal enthusiasm for electrification and self-driving technologies coming from the automobile manufacturers themselves.

There is Tesla, of course, but Ford says it will have a fully autonomous vehicle in commercial operation by 2021. GM’s self-driving research and production arm—Cruise Automation—has unveiled its latest version of a battery-powered Chevy Bolt, which has no manual controls and will be on the street without a driver next year.

All the world’s major vehicle manufacturers—Honda, Hyundai, Daimler, Renault-Nissan, Volkswagen, and Volvo—are vying to gain the edge in self-driving technologies.

At the same time, it has become clear that the last century’s gas-fueled combustion engine’s days are numbered. In many countries, diesel engines are already being banned. By 2030, only electric and hybrid vehicles will be available for purchase in most Scandinavian and EU nations, India, and Korea.

Copenhagen already has an electric fleet of 400 (BMW) cars. China is now the world’s biggest producer and market for electrified vehicles, producing 680,000 all-electric cars, buses, and trucks in 2017.

And although the United States has no federal policy mandating electrification, many states are already setting targets for electric car sales. General Motors has said that it will introduce at least 20 new electric vehicles by 2023.

Local governments are rightly concerned about the infrastructure implications of nearly every future vehicle needing access to recharging facilities.

Ride Hailing Is Here, Too

Bolstering this shift toward electrification and self-driving, of course, is the ride-hailing movement, which takes advantage of the growing expectation of on-demand transportation, and the increasing willingness of both the old and young to forgo vehicle ownership in favor of shared transportation services.

Uber has just agreed to buy 24,000 self-driving cars from Volvo in the next three years. Waymo (owned by Google’s parent corporation, Alphabet) has agreed to buy thousands of minivans from Fiat Chrysler. And as an example of the cross-functional scramble for leadership in this area, even the car manufactures themselves are getting into the fray.

General Motors is rolling out plans for a fully autonomous ride-sharing service by 2019. Nissan is preparing to launch its own Easy Ride “robot” taxi service in Japan. Ford is planning a fully autonomous ride-hailing service by 2021.

And that’s not to mention the logistics groups—Amazon, FedEx, UPS, and even the U.S. Post Office—that will soon flood the streets with (mostly electric) AV shuttles for curbside pickup and deliveries.

These companies know that as the “sharing” aspect of the AV economy kicks in, fleet ownership will quickly outpace private AV sales. That means that ride-hailing companies will soon dominate the autonomous vehicle market; and they will choose electric cars as they become increasingly cost effective and reliable.

This enormous investment in research and funding by private industry has led to early collaboration with cities, with pilots moving quickly out of the controlled testing campuses and onto real city streets where local governments have been eager to offer up their infrastructure as proving grounds: Austin, Boston, Phoenix/Chandler, Detroit, Las Vegas, Pittsburgh, Reno, San Antonio, San Francisco, San Jose, and Washington, D.C., are all actively piloting AV programs.

As the potential benefits of self-driving, electrification, and ride-hailing are becoming more obvious, and the potential threat to public transportation systems looms large, local administrators themselves are beginning to buy into electric AVs to augment their own public transit systems.

This can be in the form of the driverless bus fleets that are proliferating in the Bay Area, or a municipally owned fleet like that in Columbus, Ohio, where the city council has approved a lease-to-own option for 93 electric vehicles.

Planning Ahead

If you’re in the administration of a large community, you’ve probably already started to plan for the AV economy. A November 2017 report from the National League of Cities found that nearly 40 percent of U.S. major cities are preparing for self-driving vehicles in their long-range transportation plans.

Unfortunately, self-driving cars and electrification are too often thought of only in the context of “smart” (and usually, large) cities. But what about people living in satellite counties, suburban municipalities, and small or rural towns? What role do they play in this AV transportation and economic restructuring?

It’s important to appreciate that in many ways small towns are just as critical to the success of the AV transformation as large cities. That’s not only because many of the services that these smaller communities need locally—shopping, seeing the doctor, or simply getting out of the house to visit friends and family—can be enhanced through AVs.

Equally important, because they often commute into larger cities, suburban and rural residents are the ones who are most likely to take advantage of shared, self-driving technologies, and to participate in first-mile/last-mile AV ride-sharing from public transit hubs.

Whatever the size of the community, though, without planning, administrators may face a serious asymmetry in terms of financial clout and contractual savvy when powerful transportation companies show up on the doorstep (or at the curb). That’s why local governments—large or small—need to be actively thinking through their policy goals now.

So what should administrators, managers, and planners be doing in order to prepare for this transformation to electrification and shared self-driving vehicles? Here are several areas to consider:

Addressing the built environment/infrastructure. One of the advantages, and necessary preconditions, of self-driving vehicles is that they can go anywhere on public roads that a normal car or truck can go. Equipped with a variety of sensors, cameras, and GPS, AVs are being developed as an all-purpose alternative to human drivers, operating safely on normal highways without the need for special equipment or dedicated lanes.

Of course, it isn’t quite that straightforward. Self-driving vehicles still need well-maintained road construction and signage, and the better the infrastructure, the better they will work. More important, local governments still control the right-of-way access and are responsible for zoning and permitting.

Parking strategies may need to be revisited and parking garages repurposed. Providing safe and easy access for riders of hailed on demand vehicles may require changes to curb access and traffic flows.

A comprehensive but flexible pole policy will be necessary for mounting 5G sensors, while at the same time keeping telephone and lamp poles from becoming overburdened and ugly.

And because pedestrian traffic and bicycles will bring an autonomous vehicle to a standstill, it may be necessary to segregate AVs from pedestrian and bicycle zones to keep traffic flowing.

Policy considerations. Administrations also need to think about permitting, certifications, and speed limits, and will want to encourage—or on the other hand, restrict and regulate—AVs and ride-hailing, according to their community’s best interest.

That means having a data-collection and data-sharing policy ready before ride-hailing AV groups arrive on your doorstep. Your community may want to develop pricing incentives that will discourage congestion, promote shared ridership, or develop special provisions for children, the elderly, the disabled, or lower-income groups.

With ride-hailing services already reducing public transit ridership by an average of 12 percent nationwide, transit agencies, cities, and ride-hailing groups will need early agreement on aspects of public and private coordination at transit hubs. Eventual synchronization of scheduling and payment systems will become necessary across multiple modes of transport.

Importantly, an evaluation framework for pilot projects and contracted services should be prepared well before the request for information process takes place so that administrators have time to decide how they will assess AV proposals.

Budgeting and manpower. Another important policy issue that looms large for local government professionals is how to compensate for lost revenues. Over time, the shift to the combination of AV and shared transportation will undoubtedly change the nature of the local budget.

After all, once fully realized, the sharing, AV economy may significantly reduce—or even eliminate—many traditional revenue sources. Ride-sharing and roaming fleets of self-driving vehicles will not need to use parking meters or park in garages, and AVs will all but eliminate fees and fines for speeding, illegal parking, emissions-testing, and DUI and traffic violations. This will represent a significant loss of income for most jurisdictions.

And it’s not just revenues that will be affected. The sharing, AV economy will also mean rethinking local staffing and resource priorities in a wide variety of areas. The police force, for example, will need to adapt to different duties and a smaller presence.

Today, 80 percent of the typical city police department is involved in some way with traffic control. On the other hand, communities may need to staff new inspector, engineering, IT, and data management roles.

Outreach and public discussion. Finally, the transformation to the AV economy will require an ongoing dialogue between elected officials and administrators, and possibly most important, administrators and the public.

After all, these changes can affect a lot of people in a lot of ways, including changes to local employment, as many traditional automotive-related jobs shrink in number or even disappear.

As more people turn to ride-hailing or shared-use vehicles, parking lots will gradually become available for apartments or retail space, affecting a community’s social cohesion as well as local housing prices.

There may be public-safety concerns, and there will certainly be objections to changing methods of revenue collection.

Putting Your Community First

All of these infrastructure and policy decisions should be reflected in the city or county’s comprehensive plan, which should be expanded to cover key aspects of transportation planning and infrastructure investment priorities around AV, sharing, and electrification.

Managers and policymakers should take advantage of the time still available to think through and agree on their community’s principles and priorities. This should be done before the potentially disruptive effects of electrification, sharing, and self-driving vehicles begin to exercise control over all aspects of transportation and public policy in the future.

Dale Neef is a management adviser on smart cities and autonomous vehicles, Loudoun County, Virginia (dneef@daleneef.com). He serves on the American Planning Association’s Smart Cities Task Force, and is the author of Digital Exhaust: What Everyone Should Know About Big Data, Digitization and Digitally Driven Innovation (FT Press).

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!