By John Crumpton, ICMA-CM, and Jamie Wicker

The opioid addiction crisis is affecting communities of all sizes. Local government managers know that emergency responders have had to re-address how to respond to drug overdoses to save lives. They are concerned about the liability and impacts that these changes are having on law enforcement, emergency medical services, and first responders.

The long-term solution, in our opinion, is (1) educate young people of the terrible impacts that prescribed pain-killing drugs are having on people's lives and (2) collaborate with partner agencies to address the addiction from multiple disciplines. A manager's challenge is how to assist elected officials in developing goals and strategies to tackle the issue. This article discusses how Lee County, North Carolina, is implementing a multidisciplinary process to do so.

Lee County Background

Lee County is located 30 minutes south of the major metropolitan area of Raleigh/Wake County and 40 minutes north of Fayetteville/Cumberland County. The population as of 2017 exceeds 60,000 and is growing daily.

Demographically, the population is 52 percent White, 28 percent African American, 25 percent Hispanic, and 3 percent other races. North Carolina labor statistics show that financially, Lee County's per capita income is growing at around 5 percent and exceeds $38,000.

In 1999, the rate of fatal unintentional poisonings per 100,000 residents in North Carolina was 3.5 deaths; by 2012, the rate increased to 11.3 deaths or a 223 percent increase. A review of data from the county's health department shows that in the first quarter of 2016, there were 261 drug overdoses in the county. In the same quarter in 2017, that number dropped to 65.

The health department credits the Project Lazarus Task Force, along with two and half years of work, education, and cooperation with department and task force partners, for the decrease. Increased police enforcement of state laws involving prescription drugs also is reducing the amount of opioid-related drugs being prescribed in Lee County.

In both 2016 and 2017, based on the task force's data, females far exceeded males in overdoses as did whites over all other racial groups combined. Age wise, the largest group was 20 to 29 years of age.

According to the Lee County Sheriff's Office, opioid-related drugs are the largest recreational drug for youth and young adults in the county. Statistics from the county's health department back up these claims.

In 2013, in response to the increasing crisis, Lee County was one of the first counties in North Carolina to get involved with Project Lazarus, a community-based opioid overdose prevention program. Established by Community Care of North Carolina (CCNC), this $2.6 million project was funded by a grant from the Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust and the North Carolina's Office of Rural Health and Community Care.

Lee County used funding from the project to keep in place the public health promotions and education section of the health department, which was being considered for elimination due to impacts from the recession. The public health director's responsibilities were broadened to include the collaboration of various agencies working to address opioids.

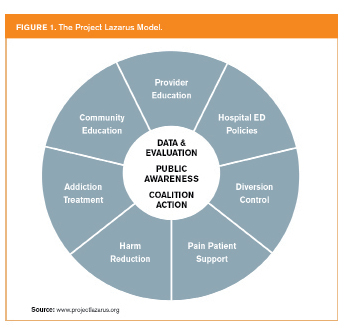

Project Lazarus' goal is to prevent opioid misuse and abuse and reduce the number of deaths from an overdose. Its model follows a multifaceted approach (see Figure 1).

In Lee County, the community outreach specialist for the health department administers Project Lazarus. With assistance from the health director and the Board of Health, overdose statistics from 2016 and 2017 show the task force is making good progress.

Staggering Impacts

Lee County Sheriff Tracy Carter began his career as a school resource officer in Lee County. For more than 26 years, he has seen the various transformations of trending drug use in young people and maintains that prescription pain killers are the gateway to opioid addiction.

Carter says, "Popping pills has been grouped with alcohol and marijuana use in the high schools. Students consider it recreational and okay since it is prescribed."

The sheriff's office is responsible for providing school resource officers (SRO) to all schools. Through these SROs, the county is trying to educate students on the escalating number of addictions that prescription drugs cause its victims. It is too early to determine if this intervention is working.

All public officials that we interviewed (See "Information Sources" on page 13) agreed that the key to eliminating overdoses is twofold. First, provide early education to people who have never used the drug. Second, make critical rehabilitation services from mental health professionals available to those who have become addicted.

For local government officials, the changes in the mental health system in North Carolina appear to be creating issues in getting people who are suffering addiction the help they need. The 2001 Mental Health Reform Act in North Carolina began to consolidate mental health local management entities (LMEs) from a total of 39 to the current number of seven. The legislature is now trying to lower that number to four to cover all 100 counties in North Carolina.

As LMEs concentrate on consolidation, the quality of care to consumers of mental health services is suffering according to a report by Governor Pat McCrory's Task Force on Mental Health and Substance Abuse.

Local mental health agencies in North Carolina no longer provide services themselves to consumers but contract with service delivery providers under the N.C. Mental Health Reform Act. A story published by the Carolina Public Press notes the coordination of services needed is not occurring because of LME's numerous contracts for service delivery.

In the case of opioid overdoses, local emergency responders are having difficulty referring patients to the proper agency for service. Patients can refuse transportation to the local hospital, which is where referrals can be made to the local mental health agency.

The new system of contracted services through local LMEs makes knowledge on how to get rehabilitation services to those that need it extremely difficult. Before consolidation, the local mental health agencies could provide services directly to patients. Now they must make referrals to their contract providers and hope that the patients seek treatment.

Local government managers can help by understanding the services that LME service providers offer and educating the first responders and supervisors on where to refer patients. This information also needs to be communicated to politicians and the public. Managers can use press releases, social media, and televised board meetings to explain these services so that the public is aware of how to use them.

Collaboration and Opportunity

In Lee County, these groups have all had discussions on the opioid problem: Broadway City Council, Sanford City Council, Lee County Board of Commissioners, Law Enforcement for Broadway, Sanford and Lee County, Duke/Lifepoint Hospital, Duke Lifepoint EMS, Lee County Health Department, and the Sandhills Center for Mental Health.

With so many interested parties and the influence of Project Lazarus, it would seem natural that all organizations would have met together to talk strategy. In small groups this has occurred; conversations with all the parties together in one place, especially elected officials, has yet to happen. There are, however, resources for local governments to use in getting these conversations started.

The North Carolina Association of County Commissioners (NCACC) is trying to jump-start conversations by promoting the county leadership's forum on opioid abuse. This initiative, started by NCACC President Fred McClure, provides a toolbox for Lee County leaders to begin engaging local elected leaders in an informed discussion of opioids.

President McClure traveled the state in July 2017, when regional meetings were being held to discuss the initiative. He gave commissioners a call-to-action at the NCACC annual conference in Durham during August 2017. Information on the toolbox can be found at NCACC.org.

The goal of the program is to develop collaborative strategies that enhance prevention, education, and treatment. The National League of Cities (NLC) and the National Association of Counties (NACo) have also released the report A Prescription for Action: Local Leadership in Ending the Opioid Crisis, which can be obtained at http://www.naco.org/events/naco-nlc-opioid-epidemic-task-force-report.

The report emphasizes goals and actions needed to end the crisis. It is an excellent tool to use when conducting a community forum on the topic. Similar to the NCACC initiative, this program requires collaboration and cooperation between multiple organizations to be successful.

For local government managers, the challenge is creating an environment where this occurs. The manager can serve as the facilitator to help officials come together to develop strategic plans addressing critical needs.

The opioid crisis provides the same opportunity for the manager to use these skills to create solutions to this problem. Like most local government problems, managers believe the opioid crisis will require time and money to solve: Time for the organizations that want to take an active part in the solution and money to pay for the staff and programs needed to address the issues.

Here are recommendations from NACo and NLC on prevention and education:

- Increase public awareness by all available means. Local leaders can use their positions to spread information on the subject.

- Reach children early, in and outside of schools.

- Advocate for opioid training in higher education. Local leaders should promote appropriate training on the potential abuses of pain management drugs to community college, undergraduate, and graduate students within their jurisdictions.

- Embrace the power of data and technology. Younger populations communicate through social media and other technological means so localities must use this technology as a tool to reach and educate them on opioid addiction.

- Facilitate safe disposal sites and take-back days for pain medicine that is not used by patients.

NACo and NLC recommendations for expanding treatment include:

- Make naloxone widely available to first responders.

- Intervene to advance disease control by implementing a clean syringe program.

- Increase availability of medication-assisted treatments.

- Expand insurance coverage of addiction treatments.

- Employ telemedicine solutions.

These are excellent first steps, but the involvement of elected officials from the federal, state, and local levels needs to increase for these efforts to be successful. Commitments of time, effort, and dollars are needed to address the epidemic.

The discussion and coordination needs to be initiated with the help of managers. This is a time for action and a great opportunity for leaders in the profession to step up and make a difference.

In addition to establishing educational forums for both political and community leaders, managers should allocate resources in their budgets for training first responders on how to identify overdose victims and how to get them to treatment centers. They can assist with public awareness campaigns, as we believe educating all residents on the issue must be the ultimate goal of the manager.

Going Forward

In Lee County, the community-wide discussion is just now beginning. Although for this local government, the first step is covered: Acknowledging there is a problem and that it needs to be addressed. The commitment of the county to Project Lazarus has helped, but more still needs to be done.

Going forward, there are numerous opportunities for collaboration and joint solutions. Both elected and appointed professionals need to take action in addressing the opioid crisis. It is a community and countrywide concern and one in which the management profession can have a major role in creating effective solutions.

Information Sources

- Victoria Whitt, Executive Director, Sandhills Mental Health, West End, North Carolina

- Ashley Graham, Community Outreach Director, Lee County Health Department, North CarolinaHeath Cain, Health Director, Lee County Health Department, North Carolina

- Sheriff Tracy Carter, Lee County Sheriff's Office, North Carolina

- Shane Seagroves, Emergency Management Director, Lee County, North Carolina

- Aaron Bullard, Emergency Management Office, Lee County, North Carolina

- Tim Lawson, Emergency Management Office, Lee County, North Carolina

- North Carolina Association of County Commissioners

- National Association of Counties

- National League of Cities

- Carolina Public Free Press (https://carolinapublicpress.org)

John Crumpton, ICMA-CM, is county manager, Lee County, North Carolina; adjunct professor; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in Master in Public Administration Program; and a doctoral candidate in Community College Executive Leadership, Wingate University, Wingate, North Carolina (jcrumpton@leecountync.gov). Jamie Wicker is a law enforcement officer, Lillington Police Department, Lillington, North Carolina; an instructor at Central Carolina Community College, Sanford, North Carolina; and a doctoral candidate in Community College Executive Leadership, Wingate University, Wingate, North Carolina (ja.wicker@wingate.edu).

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!