Like most of you, during my career as a local government administrator I have tried to support new and imaginative ways of engaging community residents. The creation of book circles, study groups, research committees, educational seminars, citizen academies, community-wide strategic planning sessions, and online dialogues were all part of my search for the holy grail of active resident involvement in community decision-making. Some of these projects were effective but they usually ended up only impacting a small group of people.

While I do consider some of these creative approaches to public engagement to have been successful projects, when I look back on my 30-year career as an administrator, I am also confronted by the many difficult times I had dealing with the resident engagement issues and conflicts that faced the communities I served.

How often did my ego and insecurities as an administrator keep me from handling community conflict well? How frequently did I view resident challenges as an accusation of my professional management and value rather than an expression of valid disagreement that needed to be heard and understood? Instead of seeking real engagement, how regularly did I hope no one would show up for meetings? After all, wasn’t it my job to keep board meetings conflict free, things running smoothly, and my community out of the glare of media coverage? In retrospect, what an unhealthy view of conflict and community engagement!

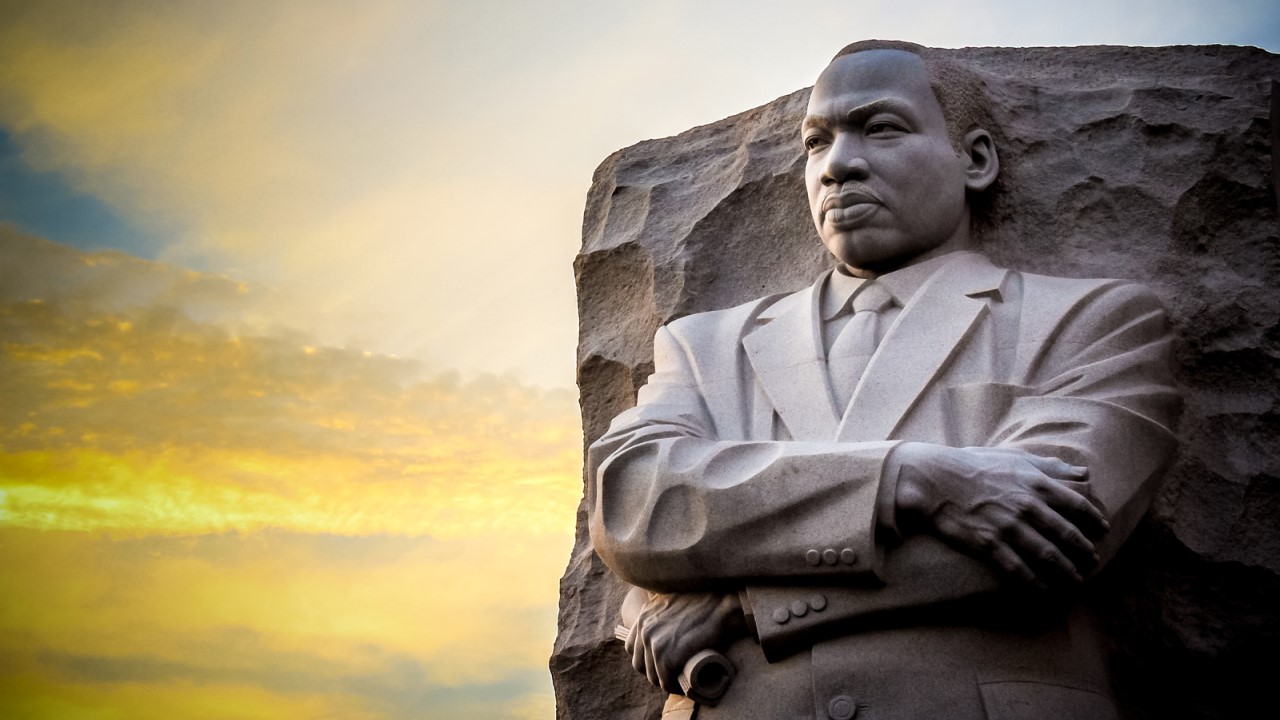

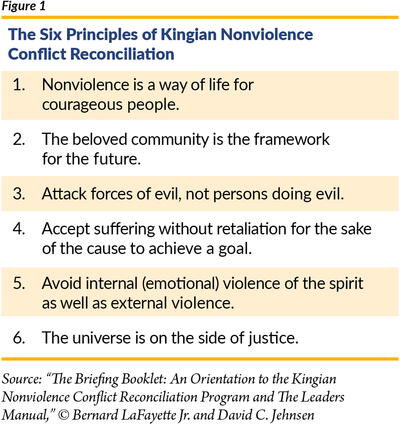

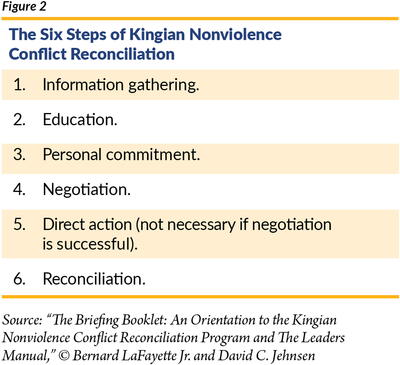

My attitude toward and understanding of community conflict and engagement was transformed as I sat in a recent training session introducing me to the principles and practices of Kingian Nonviolence Conflict Reconciliation (KNV). As the trainers explained, Kingian Nonviolence is an approach to conflict resolution that emerged from the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ‘60s. The curriculum was first codified by Bernard LaFayette, an early follower of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., working with civil rights activist David Jehnsen in the 1980s. The name “Kingian” is representative of a period in history and not just a single individual. The KNV theory and methodology utilizes the foundations of nonviolent and dialectical thinking of Hegel, Gandhi, and Judeo-Christianity, and recognizes the tremendous contribution of a great many civil rights leaders of the time.

Our Attitude Toward Community Conflict

This KNV session gave me a strong sense that what we need in our local governments is not more innovative structures and technologies for engagement, but a reimagining of the core beliefs guiding how we as administrators, elected officials, and residents view and carry out our public conversations and discourse. A reimagination of how we deal with conflict!

How have we lost our ability to see that conflict should be a normal part of life and decision-making? Shouldn’t differences in opinion be viewed as natural, as well as the importance of negotiation, compromise, and yes, even reconciliation with those who might oppose us following disagreement?

Nonviolent public management, as proposed by KNV, is really not much different than what most of us practice every day. We strive to frame issues well so that conflicts can be

better understood and resolved. We seek to build community in fair and equitable ways. We attempt to face intense controversial problems with neutral facts, research, and wisdom. I see KNV as supportive for our work and for the ICMA Code of Ethics, offering with it stories of successful nonviolent confrontation with racial discrimination, added emotional resources, inspiration, and tools to increase our resilience as we face the difficulties of the public arena today. KNV’s timeless principles and practices can serve as guideposts for us when we lose our vision or sense of why we got into public service in the first place.

Courageous Public Management

It goes without saying that our responsibilities must be carried out without violence, both physical and emotional. Yet being nonviolent can be misinterpreted. It does not mean to run away from conflict, hide from it, or hope that it disappears. It means we must face conflict consistently and courageously, with all the positive spiritual, emotional, and intellectual energy within ourselves. A nonviolent approach asks us to not respond in kind, or retaliate against, abusive criticism or violence and be willing to sacrifice for the sake of what we believe to be true. Our job as a nonviolent public manager is to understand conflict as a neutral element that needs to be managed wisely so it can offer the creative opportunity for improving relationships in our communities. Especially in today’s contentious public square, we also need to be keenly aware of how we as appointees, our elected officials, and our residents may engage in emotional violence when relating to each other. Name calling, shouting down, or failing to listen to an opponent is not providing an opportunity for true engagement.

A Framework for the Future

KNV offers a fundamental shift in how political change is usually made in our communities. Rather than an “us versus them” adversarial approach, or trying to discredit and vilify opponents, there is an attempt to work in such a way that would potentially turn our opponents into allies and win general support from the community. Our commitment goes beyond just conflict resolution to reconciliation of relationships.

In KNV, conflict is never over until reconciliation takes place and the community is moving forward together. Tenet 4 of the ICMA Code of Ethics asks us to serve the best interests of all community members in a fair and equitable manner. I believe the KNV curriculum and Dr. King’s definition of community building can inspire and support these efforts. In his 1958 book, Stride Toward Freedom, King uses the Greek term agape to describe how he was able to continue to seek community with those who were firebombing his home or burning his churches. For him, agape means love in action, not a weak or passive love. It seeks to preserve, create, and insist on community even when others seek to break it.

Agape is a willingness to sacrifice in the interest of community and a willingness to go to any length to restore community. It is a love in which the individual does not seek his own

good, but the good of his neighbor. It is a neighbor-regarding concern for others that seeks to discover the neighbor in every person it meets. Agape is a redeeming good will for all humans and it attempts to see goodness even in our enemies.

Our North Star

Experienced and practical local government leaders may think the KNV approach is too idealistic and does not adequately consider the political difficulties facing an appointed administrator or the rough and tumble world of today’s polarized communities and frenzied social media environment. In response, I would like to end with a story shared by Kazu Haga in his brilliant little book, Healing Resistance, written about KNV Conflict Reconciliation. The story recounts how slaves walking north toward freedom along the underground railroad would find the North Star each night as their guide. They were not walking to the North Star specifically — it was millions of miles away — but they knew if they kept moving toward the star, they would eventually get to the freedom they desired.

Kingian Nonviolence Conflict Reconciliation can serve as our North Star as we work toward it every day, holding on in faith to that famous phrase popularized by Dr. King: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

DAVE TEBO is a recently retired ICMA-CM and owner of WI2 Community Consulting, LLC, in Greenville, Wisconsin, USA (dtebo.wi2@gmail.com).

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!