The term “social equity” is not new—it has been around for decades. But the significant gaps in equity laid bare over the past two years by the pandemic and by racial injustices, especially in public safety, have created a new sense of urgency for cities, counties, and towns.

Local government leaders have been attacking the equity and inclusion crisis on many fronts—for example, through policing reform, through modernization of election and voting practices, and through ordinances, policies, rules, and offices to advance equity. One overlooked tool that offers an opportunity for real change through structural reform is the local government’s charter.

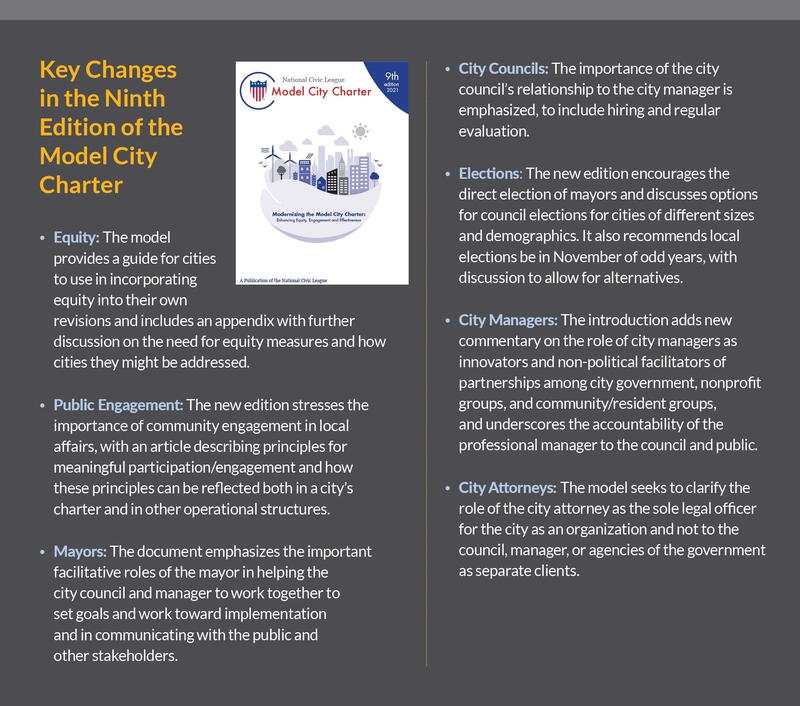

The heart of local governance structures, at least for most counties and municipalities, is the charter, the document that lays out the “rules of the game.” This is where fundamental reform can begin. ICMA and the National Civic League worked together over 100 years ago to reform local governance, creating a Model City Charter to help guide cities to a new era of professionalism and efficiency. It addressed some of the most pressing challenges facing cities in the 1900s—structural inefficiency, political corruption, and the need for a merit system for public employees.

As we step further into this new decade, a revised and updated edition of the Model City Charter institutionalizes equity and civic engagement. Together with the National Civic League, ICMA, National League of Cities, and American Society for Public Administration worked with a Steering Committee of 22 national representatives and experts to produce the first full revision of the charter in a decade. ICMA members can access a free copy of the new edition of the Model City Charter here.

Including Equity as a Core Value

In addition to guiding local governments to become more efficient, ethical, professional, and accountable, the revised charter includes equity as one of these core values. ICMA Research Fellow Benoy Jacob, in his study, “Governing for Equity,” pointed out that “while typically viewed as a national issue, the problems of inequity, whether social, economic, or otherwise, often manifest most clearly at the local level.” Examples of charter changes that can drive lasting improvements in social equity include:

- Underscoring the manager’s role in promoting social equity throughout the organization.

- Specifying that departments, offices, and agencies adopt an equity lens to shape decisions and activities, including personnel, land use, development, and environmental planning.

- Emphasizing the importance of reflecting social equity in budgeting, performance assessments, and access to services.

- Stating that principles of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion should guide the execution of public engagement activities.

- Ensuring that elected offices are fully representative of the community by establishing procedures and districts that encourage representation of all elements of a community.

Importantly, equity may be defined and implemented in a variety of ways based on the characteristics and interests of a community. Therefore, this work requires an inclusive community engagement process to gather insights and direction from the community itself.

Increasing Civic Engagement and Democratic Practices

The revised charter elevates the importance of just, inclusive, and equitable public engagement; the values of democratic professionalism and ethics; and community-centered governance and problem solving. These changes are driven by many forces, including:

The complexity of the challenges facing local governments. Leaders must negotiate tensions and tradeoffs among competing, underlying public values in collaboration with community members, through deliberative problem-solving, planning, and decision making, rather than solely through technical expertise or adversarial politics. In addition, community members have tremendous problem-solving capacities. Many public problems simply cannot be addressed without the support of large numbers of people.

The need to bridge divides. More participatory and equitable practices have achieved success in building mutual understanding and establishing consensus across different groups of people.

Equity and engagement require one another. Making public engagement more inclusive and participatory will help produce more equitable outcomes for a wider range of people, as will engaging people in evaluating whether policy outcomes are in fact equitable.

The importance of civic health. Strong, ongoing connections among community members, robust relationships between community members and public institutions, and positive attachments between people and the places where they live are highly correlated with a range of positive outcomes, from better physical health to higher employment rates to better resilience in the face of natural disasters.

Inclusive civic engagement is recommended for all charter sections involving public outreach and deliberation. For example, city departments and offices should include civic engagement in their planning and decision processes, elected positions should incorporate engagement in their processes, and the public should be considered a partner in all city affairs.

Producing a Lasting Change

It is not a coincidence that the public holds a higher level of trust for local government compared to federal and state governments—that was the intention of the early authors of the model charter and the reason for the emphasis on professionalism and integrity. Inequality and lack of public engagement undermines trust and community. Unless we include the full community in decision making and to achieve equitable outcomes, local governments would lose not only the public’s trust, but its cooperation as well. Engaging your residents in revisiting your charter is one of the most important steps you can take in creating a thriving community that reflects its most fundamental and democratic values.

MARC OTT is executive director/CEO of ICMA, Washington, D.C.

DOUG LINKHART is president of the National Civic League.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!