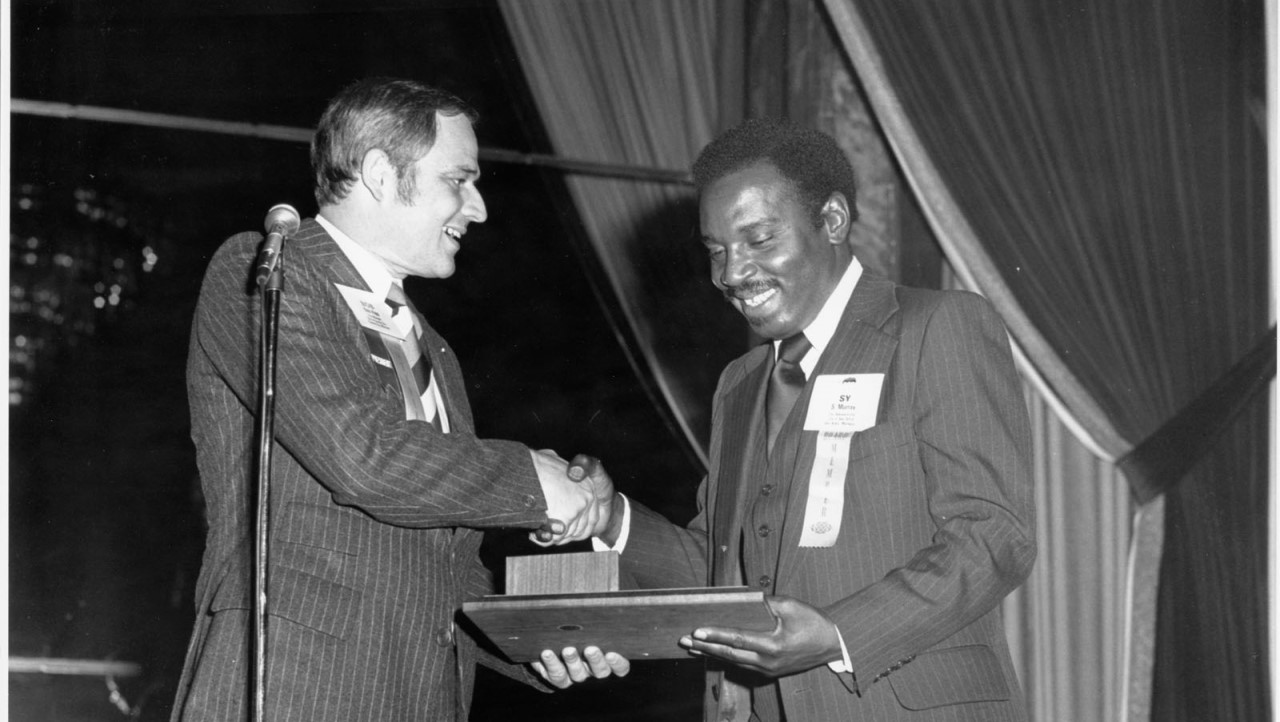

The 1970s we often say was the decade to be good to minorities, especially African American minorities . . . several of the rights that we fought for in the 1960s, we got them in the 1970s. —Sy Murray, former city manager, Cincinnati, Ohio, and the first African American President of ICMA

Against the backdrop of social upheaval and change, ICMA established a Task Force on Race Relations in 1969 that described a series of actions that the association should consider for the 1970s and beyond. The decade that was ending had ushered in new policies and programs; social movements and campaigns that began the process, which continues today, of breaking down and eroding the sinews of segregation and social injustice.

Like other institutions and associations, ICMA was evolving with the social changes; much too slow as some would argue, while others felt the pace was far too quick. With the 1969 task force, the association’s leadership, as ICMA’s president noted in an editorial three years later, “made a clean break with the apologists, and we established for our profession an activist role—activists ready to correct injustices and eliminate inequities.”1 Tucked into the task force report was the recommendation to support the inclusion of more African Americans (as well as other underrepresented populations) in urban management. Coupled with some well-timed funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and strong partnerships with several councils of government and universities, ICMA started a new Minorities in Management program.

This article looks back to the formation, operation, and evolution of ICMA’s Minorities in Management job placement programming, which launched in 1970, and continued in various forms for several decades.

1960s: Courage, Skill, and Good Will Needed

ICMA records indicate that the association’s conversations on race relations, social justice, and inequality began to increase throughout the 1960s. One 1964 article in PM magazine noted, “It is the duty of city managers to provide community leadership in a difficult period of time.” This same article, which was derived from a keynote presentation at ICMA’s 1963 annual conference stated:

It is the urgent deadly serious business of you as the dedicated, professional officers of the peace to lead your communities through one of the most difficult and dangerous periods of transition this nation has had to face. It will largely depend on your courage, skill, and good will as to how the country fares.2

Throughout the 1960s, additional content was published and events organized as the civil unrest in America’s cities continued to grow. A 1967 edition of PM focused on the summer of riots and civil unrest that happened throughout the United States. In 1969, ICMA launched the Urban Data Service, for which the first edition was titled, The American City and Civil Disorders.3

Guest editorials by leading voices of the era—including Otto Kerner, governor of Illinois and chairperson of the U.S. Riot Commission Report, the final output of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders—appeared in PM and as part of ICMA’s conferences and events.4 Indeed the Riot Commission Report had several criticisms of local government management, particularly in areas that were home to large populations of socioeconomically challenged populations. Specifically, the report called out the need for more diversity in city hall, suggesting that “(l)eadership by city government in this vital area is of urgent priority.”5 At the time of the Kenner Commission, only three African Americans had been appointed to lead cities: James Johnson (1968, Compton, California); Gladstone Chandler (1970, East Cleveland, Ohio); and Sy Murray (1970, Inkster, Michigan).

1970s: A Brighter Future?

ICMA’s Minorities in Management program was started with a modest grant from HUD. The funding was part of HUD’s 701 Planning Grant program that was overseen by Assistant Secretary Samuel Jackson, a prominent African American in the Nixon Administration and former civil rights activist. Initial partners included the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments, the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, Howard University, and the University of Michigan. During the program’s first year, six students were selected for participation in both Michigan and Washington, DC. In 1971, regional councils in Denver, Colorado, and Maricopa County, Arizona, joined the program, providing additional placement opportunities. Additional funding was received from the Ford Foundation to advance the program as well.

During the first three years, 30 participants matriculated through the placement program, including not only African Americans but also Hispanic Americans as well. The program did not lead to an immediate spike in the diversity of city managers. In most cases, graduates were hired into other local government positions; however, several graduates, as well as those from other programs, would soon become professional managers. By 1974, the program had a total of 40 participants, of which 28 had been placed in various positions with local government.6

ICMA’s first director for the program was Richard Monteilh. After leaving ICMA in the mid-1970s, Monteilh served in highly distinguished public and private sector roles, including time as the city administrator for Newark, New Jersey; the award-winning director of Washington, DC’s Department of Housing and Community Development; and as the executive director of the Metropolitan Atlanta Olympics Games Authority.

In 1975, the Minorities in Management effort was renamed the Minorities Executive Placement Program (MEPP). As part of this change, ICMA began expanding the services offered by the initiative. State associations were recruited to help place candidates. According to a 1976 ICMA Newsletter, the profiles for 360 active candidates were included in ICMA’s MEPP database.7 Similarly, the numbers of African American city managers in the profession had grown, but remained frustratingly small. In the year that the United States celebrated the bicentennial, there were only a small number of African American city managers in the profession, including Robert Bobb, Kalamazoo, Michigan; Ronald A. Davis, Riviera Beach, Florida; Melvin Farmer, Benton Harbor, Michigan; Richard Knight, Carrboro, North Carolina; Edwin Robinson, East Cleveland, Ohio; Elijah Rogers, Berkeley, California; and David Williams, Inkster, Michigan.8

In 1977, the MEPP was led by ICMA project director Michael Rogers, who would later become the first African American executive director of a council of government when he was hired to lead the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments in Washington, DC. Rogers came to ICMA from a position as assistant city manager in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Under Rogers’ leadership, the MEPP evolved in strategy and services. By November 1977, the program had helped place more than 350 minorities and women in local government management and made more than 700 referrals. Additionally, the number of cities participating in the program grew from 85 to more than 200.9 By 1979, the program had successfully helped place more than 500 professionals in local government positions, even as the number of African American city managers remained smaller than anticipated. Rogers would eventually join the ranks as the city administrator for Washington, DC.

To congratulate the program, the Honorable Ron Dellums, representative from California, addressed the House of Representatives, saying:

Mr. Speaker, professional management of our Nation’s cities is more crucial today than in the past because of the myriad of urban problems we face. Due to the dedication of these appointed administrators, city problems are being tackled and solved … I think it is appropriate that we recognize the newly appointed managers and wish them well in their task of helping our cities run better thus insuring a brighter future for all citizens.10

Throughout the latter part of the 1970s, other notable milestones occurred. In 1978, Alfred E. Smith became the first African American county manager, when he was hired by Surry County, Virginia. Later that same year, Sherry Suttles, who at the time was the executive assistant to the city manager of Long Beach, California, was elected to the ICMA board. Frank Wise, the assistant city manager of Savannah, Georgia, joined her that year on the board. A year later, Sherry Suttles was hired by the city of Oberlin, Ohio, and became the first female African American city manager in the profession.

1980s and Beyond: Evidence of Change

ICMA’s minority placement programming continued into the 1980s. The first generation of African American city and county managers were now seasoned professionals overseeing jurisdictions in different parts of the country; however still not in very large numbers. Writing in PM Magazine, Elijah Rogers and John Touchstone, however, presented an optimistic outlook on the future for African Americans in the profession:

As we enter the 1980s, there is evidence of change in the historical trend for blacks to enter the profession primarily in urban areas with majority nonwhite people. Cities such as Berkeley, California, Little Rock, Arkansas, and Cincinnati, Ohio, show that black managers are beginning to be hired in cities with a white majority, based on their experience and competence in the overall management of local governments.11

By 1982, ICMA’s external funding from HUD and the Ford Foundation had dried up. At this time, the MEPP—now known as the Minority Recruitment and Placement program—was funded through a combination of annual dues from subscribing communities and individuals that paid to enroll in the talent bank placement service. Some still expressed concern that the pacing and momentum of African American men and women entering the profession could remain stagnant or slow. Lenneal Henderson, ICMA’s 2020 Local Government Research Fellow, notes in a PM article 28 years prior:

The future of black participation in the urban management profession will depend upon the generation of more financial and human resources for training and developing such professionals. … Without renewed and increased resources, the increasingly arduous struggle of minorities to penetrate and advance in the urban management profession will suffer a bleak future.12

In 1983, several alumni of ICMA’s minority placement programming helped to establish the National Forum for Black Public Administrators (NFBPA), which continues to this day as a voice of African Americans in state and local government. Additionally, 1983 was the year that Sylvester Murray was elected ICMA president, becoming the first African American to hold that position in the history of the association. Also joining the ICMA board that year was John P. Bond, a founding member of NFBPA.

By 1986, ICMA’s diversity in management efforts had become the Talent Referral Service, which continued to offer placement support for an increasingly diverse pool of candidates aspiring to work in local government management. As the 1990s loomed, ICMA’s board once again authorized a task force on minority and women recruitment for local government management. A final report was requested for presentation no later than the September 1990 meeting of the executive board. At the request of the committee’s participants, the project was renamed the Task Force on Diversity.

By the end of the 1980s, ICMA’s primary means of job placement services evolved again, becoming the Job Opportunities Bulletin (J.O.B.). Started as a partnership with NFBPA, the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA), and the American Public Works Association (APWA), J.O.B. was printed and distributed until 2006, and then available digitally through 2012. At that time, all ICMA newsletters were consolidated into a single weekly update with jobs for all candidates.

Conclusion

While the election of Sylvester Murray and the establishment of NFBPA in 1983 may not have been the end of ICMA’s efforts, it can be argued that these two milestones may have been the “end of the beginning”13 of ICMA’s efforts to directly support the placement of more diverse populations in the profession. The association’s efforts to promote diversity continues even to the present day, but the activist role described by ICMA President Graham W. Watt in PM’s 1972 edition devoted to “minorities in management” had reached a noon-tide moment by the early to mid-1980s.

From its earliest days, the Minorities in Management program was not solely about placing African Americans. Hispanic Americans and women from all backgrounds were receiving attention as well from the association through grant funding, task forces, and affiliate organizations.14 There are many other stories to tell about diversity in the profession.

It can be argued that ICMA’s investment in placement programming 50 years ago provided help in paving the way for an increasing number of managers from diverse backgrounds, creeds, and races. Funding from the Ford Foundation and HUD also provided needed stimulus. Other larger forces were coinciding as well. The number of jurisdictions with nonwhite populations were growing, as were the number of African American elected officials becoming mayors and council members. These dynamics also helped to increase the number African Americans in local government public administration. Writing in 1982, Rogers and Touchstone suggest that:

The future of black managers is unalterably tied to the history of how and why they emerged, where they are, and the skills they possess. Black managers emerged in part because there was a need—a need for responsiveness to an increasingly important faction of the population, which had become a major political force in our major cities as well as a moral need to involve blacks in the process of self-governance throughout the country. However, for minorities to maintain the wealth of management expertise that has developed, we must find a way to ensure that there will be a continuous influx of new talent into the system.15

In 2020, ICMA’s full membership ranks include nearly 250 African American city and county managers (including deputies and assistants). Many of the first-generation African American managers of the 1970s were in communities with elected councils and populations that were majority African American. Current African American managers have been appointed in a diversity of cities, counties, and suburban communities with fewer African Americans in the community or on the council. A substantial number of these men and women have had long careers serving in multiple communities. Almost all have joined the profession without the benefit of ICMA’s aggressive early investments in placement programming. This is a tribute to their public administration, management, and leadership skills, and evidence that while change has happened slowly, it has in fact occurred.

ICMA’s and the profession’s diversity journey continues. In 2016, Marc Ott became the first African American hired to serve as ICMA’s executive director. In 2019, ICMA’s membership passed constitutional amendments making it easier for younger, and consequently, more diverse affiliate members that meet certain length of service criteria, to be selected for the ICMA executive board. Whether there will be a need for future “activist” eras to increase diversity in the profession remains to be seen. The death of George Floyd and other African Americans in 2020, the global pandemic, and other social and economic challenges have awakened familiar passions and stoked the balefires of change once again in a way that an earlier generation easily recognizes.

What today’s challenges illustrate for the profession and diversity remains unscripted and ongoing for new generations to write. Those stories, however, may begin with something like the following. On August 6, 2020, 50 years after launching the Minorities in Management program, the ICMA Executive Board elected Troy Brown, city manager of Moorpark, California, and an African American, as the association’s president-elect for a three-year term.

TAD MCGALLIARD is director, research and development, ICMA, Washington, DC (tmcgalliard@icma.org).

With substantial support and contributions from:

MICHAEL ROGERS is the former director of ICMA’s MEPP (1976-1979); and currently managing partner, Michael C. Rogers Consulting, LLC, Washington, DC (michaelcharlesrogers@outlook.com).

LENNEAL HENDERSON, PHD, is a professor, Virginia State University (lhenderson@vsu.edu).

SHERRY SUTTLES was the first female African American City Manager, Oberlin, Ohio, and is now retired.

This article is part of a series of content produced to celebrate the first 50+ years of African Americans in the city and county management profession. It has been produced almost exclusively from written records and published materials maintained by ICMA. Edits and comments have been provided by several persons noted in this article, including Michael Rogers, Sherry Suttles, and Lenneal Henderson.

Endnotes and Resources

1 Watt, Graham, W. 1972. “Editorial.” Public Management. Volume 54, Number 4. Page 2.

2 Long, Norton E. 1964. “Local Leadership and the Crisis in Race Relations.” Public Management (January 1964), Page 2.

3 ICMA, 1969. The American City and Civil Disorders. Urban Data Service Report, Volume 1, Number 1.

4 Kerner, Otto (Chairman), 1968. The U.S. Riot Commission Report. Bantam Books.

5 Ibid, page 294.

6 Borut, Don. 1974. ICMA Training Programs. Public Management. Volume 56. Number 4. Page 17.

7 ICMA, 1976. January 15, 1976, ICMA Newsletter.

8 ICMA, 1976. November 22, 1976, ICMA Newsletter.

9 ICMA, 1977. November 7, 1977, ICMA Newsletter.

10 U.S. Congress, 1979. Congressional Daily Record, February 27, 1979.

11 Rogers, Elijah, and John Touchstone, 1982. “Black Administrators—An Historical Perspective,” Public Management. Volume 64, Number 6, Page 14.

12 Henderson, Lenneal, Dr. 1982. “Beyond Equity: The Future of Minorities in Urban management,” Public Management. Volume 64, Number 6, Page 2.

13 Winston Churchill said after victory in the Torch Landings by Allied Force in North Africa in World War II: “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

14 De Hart Davis, Leisha et al 2020. “Near the Top: Understanding Gender Imbalance in Local Government Management,” Local Government Review, February 2020, Volume 5.0.

15 Rogers, Elijah, and John Touchstone, 1982. “Black Administrators—An Historical Perspective,” Public Management. Volume 64, Number 6, Page 14.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!