Improving sustainability has increasingly become a focus of local governments, with almost 50 percent of respondents in a 2015 ICMA survey identifying environmental protection as a priority in their jurisdiction.1 New National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) research focuses on one potential pathway for a local government and its electric service provider to partner and achieve joint clean energy goals: franchise agreements.2,3,4

Franchise agreements are a negotiated contract between an authority having jurisdiction (AHJ) and an electric service provider, granting the utility the right to serve customers in the AHJ. The contract often specifies the period of service and a fee remitted back to the jurisdiction, and commonly includes stipulations regarding a utility’s right of way to install and maintain electrical infrastructure.

Franchise agreements are often set for significant periods of time, sometimes upwards of 20 years, offering a rare opportunity for local government leaders to negotiate and

create obligations for progress on long-term community sustainability goals.

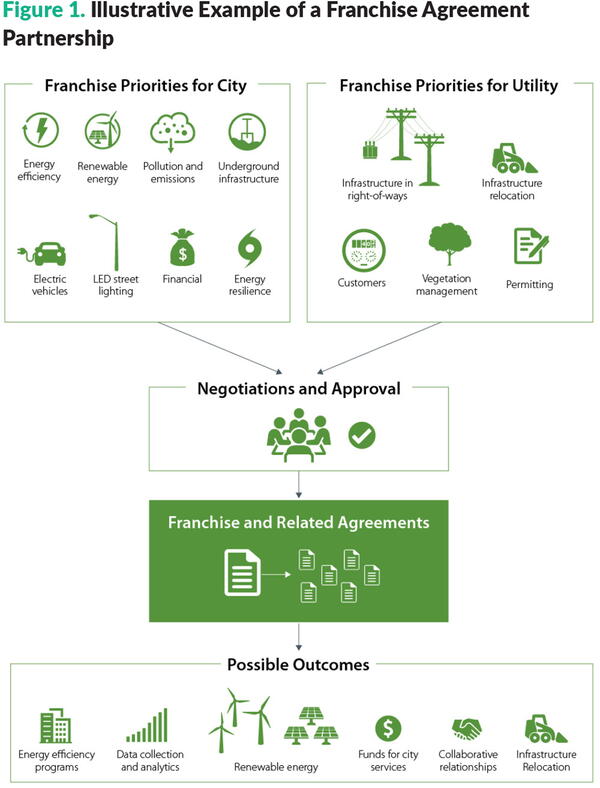

Some local governments have incorporated other energy objectives into franchise agreements—or have signed agreements in parallel—that commit the AHJ and utility to work together to achieve joint energy goals. When franchise and related agreements are implemented, the local government and utility can deliver a wide variety of outcomes, including additional revenues for municipal services, new renewable energy projects, and more collaborative working relationships between parties (see Figure 1).

To better understand the potential for franchise agreements to serve as vehicles to achieve clean energy goals, NREL researched the extent to which municipalities have the authority to enter franchise agreements, how many have pursued additional energy objectives in or alongside their agreements, and to what effect these objectives have been pursued.

Franchise Authority and Energy Objectives

NREL used a two-pronged data collection approach to build a franchise agreement dataset that includes 3,538 municipalities. NREL began by searching for franchise agreements via public utility commission docket databases; municipal code databases, such as MuniCode and General Code; and other web-based searches. NREL augmented this secondary data collection with primary interviews with state public utility commissions, state municipal leagues, electric service providers, and municipalities.

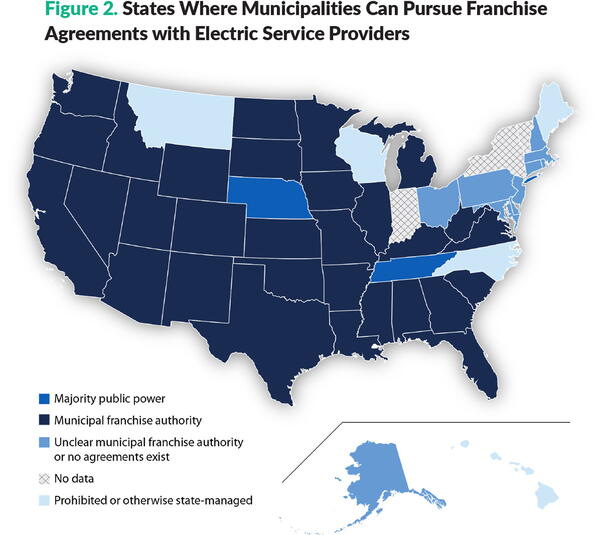

From the data set, NREL concludes that municipalities in 30 states can legally pursue franchise agreements with their electric service providers (see Figure 2). Five states

are prohibited from negotiating their own agreements (Hawaii, Maine, Montana, North Carolina, and Wisconsin), while two other states are majority public- or municipal-owned power, where cities may be unlikely to self-impose franchise agreements and related fees (Nebraska and Tennessee). NREL concludes that municipalities in 10

other states, largely in the competitive market eastern states, also do not have access to this opportunity. Finally, NREL had insufficient data to make definitive claims about

Indiana, New York, and Vermont.5

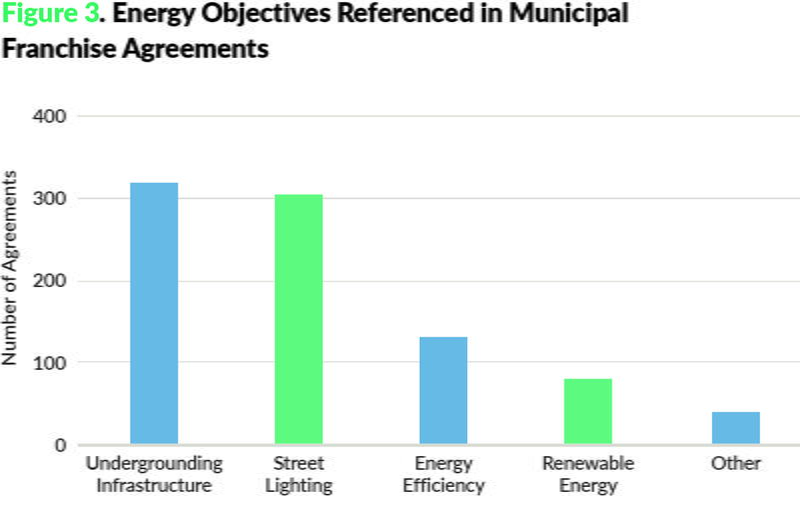

A total of 467 cities (13 percent of cities in the data set) were identified to have either adopted franchise agreements or a franchise-related agreement with one or more energy-related objectives. NREL coded these references into one of five categories: energy efficiency, renewable energy, street lighting, undergrounding infrastructure, and other (i.e., electric vehicles (EVs), service reliability, and infrastructure strengthening).

Two energy objectives—undergrounding infrastructure and street lighting—were the most common objectives referenced in franchise or related agreements, followed by energy efficiency, renewable energy, and other objectives (see Figure 3). Though references to energy efficiency and renewable energy are significantly lower, these have been increasing since 2006. Ultimately, most efficiency or renewable energy references are nonbinding or require electric service providers to inform municipalities of existing or upcoming energy-related programs. Even so, some cities and utilities have agreed to binding commitments, including providing funds to support certain municipal projects or programs.

Over 1,200 cities in the data set have franchise agreements expiring between 2020 and 2040. Most existing franchise agreements have terms exceeding 20 years, so many of these jurisdictions may lack institutional knowledge of these agreements. NREL completed five case studies of cities that have successfully negotiated a franchise agreement that also addressed renewable energy including:

- Chicago, Illinois.

- Denver, Colorado.

- Sarasota, Florida.

- Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- Salt Lake City, Utah.

These five cities were selected for a variety of reasons, including geography, population, and utility variation. All five cities have also adopted unique energy stipulations

in their agreements that demonstrate the wide variation across city approaches used. Here, we focus on the results of one case study: Sarasota, Florida, along with the

aggregate lessons learned across all the case studies.

Case Study Snapshot: Sarasota, Florida

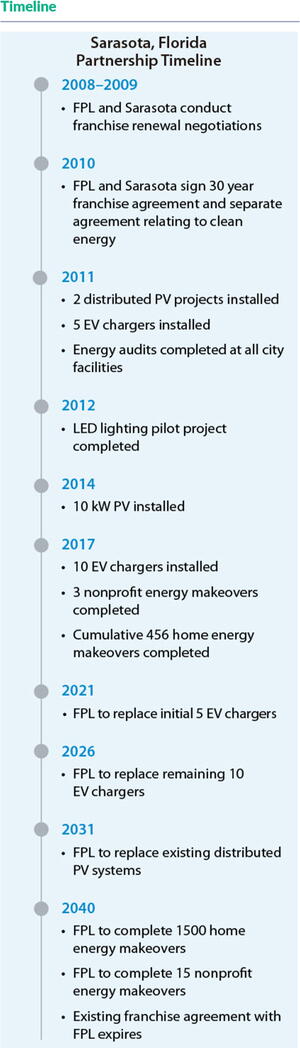

The city of Sarasota, Florida (population 57,000), is served by Florida Power and Light (FPL), and began discussing renewing its franchise agreement with FPL in 2008. The

city had a keen interest in pursuing additional renewable energy generation to offset community load and a shorter franchise term (five years), while FPL was interested in pursuing a longer-term contract (30 years) that provided more investment certainty that excluded other energy objectives.

In 2010, the two entities signed a new 30-year franchise agreement, along with a separate Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency, and Energy Sustainability Agreement

(Renewable Energy Agreement) to codify FPL’s clean energy commitments to the city.6 This parallel agreement included a variety of energy projects addressing energy efficiency, renewable energy, and electric vehicles, among others.

FPL and Sarasota have been implementing these agreements for almost 10 years. Both entities provide biannual updates to the city commission on activities in relation to the Renewable Energy Agreement. As required by the agreement, FPL has successfully:

- Deployed five EV charging stations in 2011 and added 10 more charging stations in 2017.

- Provided $2,000 for municipal personnel to attend a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design course in 2011.

- Completed 27 energy education presentations at schools in Sarasota from 2011 to 2017.

- Conducted energy audits at all city facilities.

- Implemented 456 of 1,500 and five of 15 residential and nonprofit energy makeovers, respectively.

- Installed a 5-kW rooftop PV project at BayHaven Elementary in 2011, five pole-mounted solar panels at the city-owned Van Wezel Performance Arts Hall in 2012, and a 10-kW rooftop PV project at a nonprofit conservation education facility, Save Our Seabirds, in 2014.

Lessons Learned for Negotiating Energy Objectives into Franchise-Related Agreements

Sarasota and the other four case study cities all had unique lessons learned related to their local context. Even so, NREL identified seven key takeaways transcending the five cases, including:

1. Mutual understanding of authority and goals helped cities and utilities agree on energy-related terms in four of the five cases. Excluding Chicago, interviewees from all cases noted the importance of understanding what was possible via a partnership between a city and utility. Emphasis on pilot projects or working together on enabling other higher-impact projects via franchise fee increases or enabling state legislation are all possible outcomes from these partnerships. Understanding opportunities and limitations up front can help cities and utilities successfully negotiate agreements.

2. Utilities were willing collaborators with municipalities pursuing energy objectives in two of the five cases. Interviewees in Minneapolis and Salt Lake City noted that city and utility personnel were aware of ongoing and contentious municipalization discussions and were interested in partnering to find common ground to avoid a similar situation. In addition, a growing list of utilities are interested in deploying more renewable energy to meet load, including Xcel Energy, who announced a 100-percent carbon-free energy goal by 2050 in 2018.7 Other jurisdictions pursuing renewable energy objectives may benefit from partnering with more proactive utilities interested in similar goals.

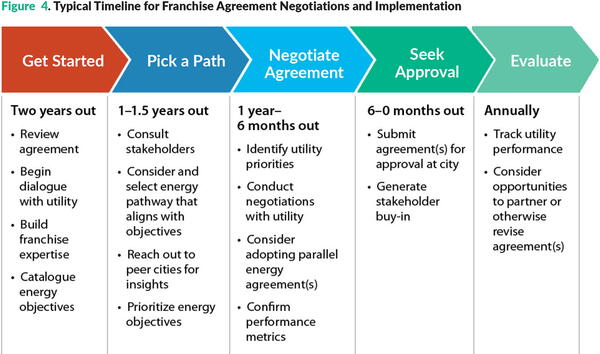

3. The negotiation process took about two years to complete on average and unfolded over five stages in all five cases. Either the city or utility initiated the process and cities began by reviewing their energy objectives and pathways (see Figure 4). Once a pathway is selected and objectives are prioritized, the jurisdiction can begin to negotiate the terms of the franchise and related agreements. In most cases, the AHJ will only need to secure the support of elected officials to approve the franchise agreement, but others may need to seek voter approval, as occurred in Denver. Once implemented, local government and utility personnel may work together to report on performance.

4. Building internal, or pursuing external, expertise helped city personnel understand negotiation opportunities and limitations in all five cases. Three of the five cities (excluding Minneapolis and Salt Lake City) sought third-party, often legal, expertise before negotiating their franchise agreements. Given these agreements exceeded 20 years, these cities lacked institutional knowledge of the previous negotiation process. If a jurisdiction cannot secure third-party support, they may still benefit from reaching out to other peers that have recently negotiated agreements, requesting information from municipal leagues to gain perspective on the process, and relying on internal career civil servants that may also have relevant legal and energy-related expertise.

5. Negotiating franchise agreement length was one of the most contentious elements of the process in four of the five cases. Two cities (Salt Lake City, Minneapolis) renegotiated franchise agreements with significantly shorter terms (five and 10 years, respectively) than the national average (20 years), while Denver had the opportunity to exit their franchise agreement at 10 years. Shortening franchise agreements is one avenue to strengthen utility accountability to clean energy goals and provide flexibility given a rapidly changing power sector. However, these goals may conflict with the interest of the utility to secure long-term contracts that provide investment

certainty. Several cities compromised on this issue by negotiating energy objectives into or alongside franchise agreements.

6. Four of the five cities adopted separate franchise and clean energy agreements, as opposed to integrating energy objectives into the franchise itself. Excluding Chicago, each city adopted a separate energy-related agreement that outlines the goals and partnership between the city and the utility. These agreements outline energy objectives, principles, and plans for implementation that often call on parties to commit staff, develop work plans, and complete regular (annual, biannual) progress reports. Utilities favor this approach because they view franchise agreements as purely related to access to the public right-of-way. Thus, local governments might consider using their franchise agreement negotiation as a starting point to develop a parallel agreement addressing renewable or other energy objectives.

7. Collecting data and tracking agreement implementation performance is an essential, though ongoing, challenge in all five cases. Four of the five cities (excluding Salt Lake City) have five or more years of implementation experience. Interviewees noted that at the outset of implementing a franchise or related agreement it may be unclear what data the utility and city should be collecting. This can make it challenging to design the monitoring and evaluation aspects of a franchise agreement that are essential to gauge impact. Establishing a clear but flexible data collection, management, and review process in or alongside the franchise agreement may help mitigate this issue and provide an avenue for more accurately tracking performance throughout the agreement life cycle.

Conclusion

In summary, local governments can leverage franchise negotiations to help achieve their clean energy goals. Whether individual cities pursue a similar approach to those outlined in the case studies will depend on their own internal decision-making processes, as well as their existing relationships and negotiations with their electric service providers. NREL’s research provides guidance on how some local governments have approached these discussions, serving as a foundation for others to make more informed decisions.

Local governments interested in learning more about this opportunity should visit NREL’s website and related franchise agreement data, which can be found here.

JEFFREY J. COOK is a renewable energy market and policy analyst at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. He has been on staff at NREL since 2014, and focuses on state and local policy, resilience, technology cost reduction, and distributed energy resource aggregation.

Endnotes

1. International City/County Management Association. 2015 Local Government Sustainability Practices, 2015 Summary Report. Washington, DC: ICMA, 2016. https://icma.org/documents/icma-survey-research-2015-local-government-sustainability-practices-survey-report.

2. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0038092X2031183X.

3. Cook, Jeffrey; Grunwald, Ursula; Alison Holm, and Alexandra Aznar. 2020. Wait, cities can do what? Achieving city energy goals through franchise agreements. Energy Policy 44: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111619.

4. Jeffrey J. Cook, Alexandra Aznar, Bryn Grunwald, Alison Holm, Hand me the franchise agreement: municipalities add another policy tool to their clean energy toolbox, Solar Energy, Volume 214, 2021, Pages 62-71, ISSN 0038-092X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.10.091. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/

pii/S0038092X2031183X).

5. The limited data collected from municipalities in these states suggest municipalities do not have this authority either.

6. Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Energy Sustainability Agreement. 2010. Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Energy Sustainability Agreement Between the City of Sarasota, Florida and Florida Power and Light Company. https://www.sarasotafl.gov/home/showdocument?id=1008.

7. Xcel Energy. 2018. “Xcel Energy aims for zero-carbon electricity by 2050.” https://www.xcelenergy.com/company/media_room/news_releases/xcel_energy_aims_for_zero-carbon_electricity_by_2050.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!