As the United States suddenly shut down its economy due to the novel coronavirus in March, people from diverse political persuasions called for a temporary stay on evictions and forbearance on mortgage payments. This made great sense—millions were suddenly out of work and could not afford to make rent or mortgage payments. And because of the need to shelter in place to slow the coronavirus’s spread, keeping families in their homes was essential for “flattening the curve.”

But the call for a moratorium on evictions was a bit surprising because of the historically privileged status offered to homeowners over renters in the United States. The public’s embrace of avoiding evictions in 2020 is in part the result of the growing awareness that evictions are not just a result of poverty, but are in fact also a cause of poverty. Being evicted generally starts a downward spiral for families, leading to job loss, homelessness, the loss of personal possessions, and lost educational attainment for school-aged children.

The new public focus on evictions stems primarily from the work of sociologist Matthew Desmond and his Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. Desmond’s examination of landlords and evictions in Milwaukee offers compelling stories and alarming statistics about the ways that evictions devastate families for many years and cause lasting harm to fragile neighborhoods.1 Indeed, it is through inequitable processes like eviction that families and neighborhoods are kept in poverty.

With Desmond’s recent book shining a policy spotlight on evictions, many large cities like Cincinnati have begun to look for ways to reduce evictions. Providing stable, affordable housing is the keystone to any strategy to end poverty. Even before the coronavirus pandemic, eviction prevention initiatives were being approved and implemented in cities throughout the United States, such as Philadelphia, Dayton, Cincinnati, and Cleveland.

However, as states reopen economies, the forbearance on evictions will likely end this summer. With months of unpaid rent and likely continued high levels of unemployment, the United States is expected to experience a wave of evictions as several months of stayed evictions are processed at once.

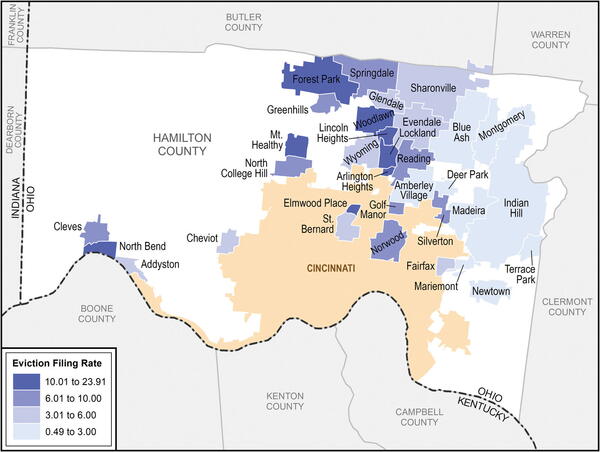

Evictions are not just a problem in larger cities. As we show using court records from Hamilton County, Ohio (which includes Cincinnati), evictions occur quite frequently in smaller communities and suburbs as well.

Professional local government managers would be wise to develop a deeper understanding of evictions in their communities and work together to develop policies and programs that reduce their overall frequency and impact. The poverty-inducing problems that stem from eviction are not limited to the urban core. Understanding evictions and finding ways to reduce their occurrences is vital to assist families experiencing poverty, and essential to smaller communities trying to sustain or rebuild economic resiliency.

Suburban Poverty in Hamilton County

Poverty has grown rapidly in America’s suburbs for the last 20 years. Brookings Institution scholars Elizabeth Kneebone and Alan Berube established in 2013’s Confronting Suburban Poverty in America that for the first time in American history “...more Americans live below the poverty line in suburbs than in the nation’s big cities.”2 Poverty, so often imagined as a largely inner-city or rural problem, is now deeply embedded in suburban America. Kneebone and Berube show that by 2010, one in three poor Americans could be found in suburbs, and suburban poverty was growing faster than inner city or rural poverty.

Between 2018 and 2019, ICMA funded a research fellowship with Tom Carroll that included an in-depth examination of Hamilton County’s inner-ring suburbs. Carroll’s findings showed that in the decade following the Great Recession of 2008, recovery among Hamilton County’s first suburbs was uneven. A handful of first suburbs near Cincinnati rebounded nicely and returned to prosperity within six years of the 2008 Recession. Most of these first suburbs were premier communities before 2008—home to the Cincinnati region’s Fortune 500 executives, well-paid professionals, and established-wealth families.

But the research also indicated that some Hamilton County first suburbs remained remarkably worse-off even a decade after the end of the Great Recession. Many modest middle-class and working-class communities saw deep declines in their total tax bases, increased poverty rates, and a loss of residents. As the middle class became smaller, so too did the number of middle-class communities. The decade following the 2008 Recession was one of stark suburban divergence within the Cincinnati I-275 beltway, and this bifurcation of suburbs into stable or declining is occurring in other American metropolitan areas, too.

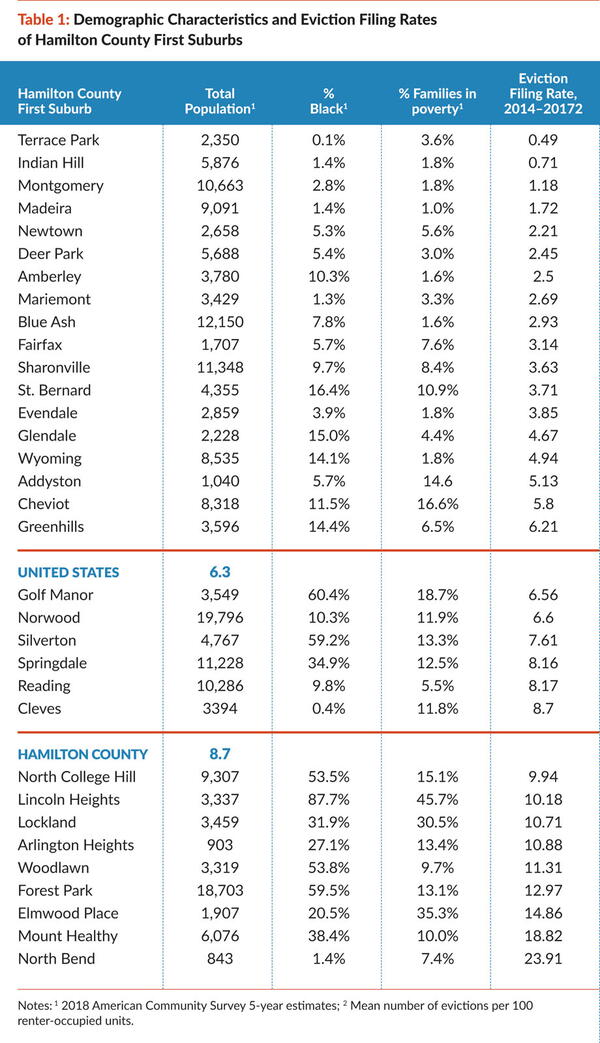

At the same time as Carroll’s ICMA-funded research on first suburbs, Johns-Wolfe partnered with community organizations to examine evictions filed in Hamilton County between 2014 and 2017. Her study showed, among other things, that the eviction filing rate of 8.7 per 100 renter-occupied units in Hamilton County was above the nation’s average of 6.3. Additionally, among a sample of filings from 2017, fewer than 1% were decided in favor of the tenant.3

This study’s findings caused numerous civic leaders in Cincinnati to discuss what could be done to reduce evictions. And while Hamilton County leaders also took notice of the high rate of eviction revealed in this study, smaller communities have had very little discussion about evictions as a public policy problem.

The lack of discussion in suburbs is not because evictions are uncommon outside Cincinnati. Instead, it is because there is a perception that evictions are uncommon outside Cincinnati. Table 1 shows the average eviction filing rates from 2014 to 2017 in the 33 first suburbs studied as part of the ICMA research fellowship.

Fifteen of the 33 smaller first suburbs in Hamilton County have an eviction filing rate above the national average of 6.3% per year. Ten of the 33 first suburbs have an eviction filing rate equal to or greater than Hamilton County’s overall average of 8.7%, and eight of the 33 first suburbs have an eviction filing rate above 10% annually. The community with the highest eviction filing rate in Hamilton County—an astonishing 23.91%—is North Bend, which is home to only 857 residents.

Consistent with scholarly research, evictions in Hamilton County tend to be more common in communities with greater percentages of residents who are black and/or below the poverty line. And many of these first suburbs with high rates of eviction are also those that have experienced population losses, spikes in poverty rates, and shrinking tax bases. Evictions and suburban decline generally go hand in hand.

Policy Implications

Carroll’s ICMA-funded research showed that a growing number of inner-ring suburbs should be concerned about the suburbanization of poverty and its causes. Many suburbs that were once solidly in the working and middle class of the United States are declining at an accelerating rate.

If suburban leaders should be increasingly concerned about the rise in poverty, suburban leaders should also be concerned about evictions. Evictions are not just a result of poverty, but they cause it. The ability of local governments to arrest or reverse decline is dramatically hurt by a high number of evictions.

The first thing for local government leaders to do is to understand evictions. Desmond’s book and website (EvictionLab.org) are excellent places to start. Then, they should gather data on the rate of evictions in their communities and compare it to county or peer communities.

Is your community’s eviction filing rate greater than the national average? How does your community’s eviction rate compare to neighboring and peer communities? Are a few landlords responsible for most of the evictions in your community, and does your municipality have other problems with these particular landlords, such as property maintenance or high rates of public safety runs? City managers need to dig deeply into this area to understand the contours of evictions in their area.

Beyond this, ICMA members should examine ordinances and programs that level the playing field between landlords and tenants. Desmond notes 90% of landlords are represented by attorneys in eviction cases, and 90% of tenants are not. Partnerships can be forged with legal aid societies and housing advocates to prevent evictions. Nonprofit partners might be able to provide rental assistance programs to bridge a suburban family suffering a small temporary financial setback. It is far cheaper to avoid homelessness than it is to rehouse a family after they are evicted.4 Evictions are expensive for landlords, too.

Local government regulations such as rental registration programs and rental inspections will ensure better housing conditions. Suburban leaders need to examine ways to create affordable housing so that communities are welcoming to all. We must rewrite our zoning codes to ensure these ordinances provide a mixture of stable and quality low-income, workforce, and market rate housing.

Smaller cities will increasingly face Wall Street landlords with a financial incentive to evict and then raise rents. When banks found themselves in possession of literally tens of thousands of single-family homes after the 2008 Recession, Wall Street hedge funds (called Real Estate Investment Trusts, or REITs) pooled money and acquired discounted houses from overwhelmed banks. REITs have a higher rate of eviction than your traditional landlord.5 Your community may well already have single-family homes that are no longer available for purchase, but instead are owned by large, sophisticated, and distant corporations.

Eviction prevention has become a big city public policy focus. As a society, we are now starting to understand evictions are extremely damaging not just to families, but to the communities where they take place. But suburbs and smaller communities—especially those facing decline—are not at all immune to evictions and their lasting negative consequences.

Stable housing for sheltering in place has proven to be vital in response to the global pandemic. But stable and affordable housing has been and always will be a key part of community stability even long after the COVID-19 pandemic has subsided. We hope this brief analysis of evictions in suburbs in one urban county sparks a broader conversation about how local governments can promote policies to reduce evictions for the good of both modest-income families and challenged communities.

ENDNOTES AND RESOURCES

1 Desmond, Matthew. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. New York: Crown.

2 Kneebone, Elizabeth and Alan Berube. 2013. Confronting Suburban Poverty in America. Washington, D.C. The Brookings Institution.

3 Johns-Wolfe, Elaina. 2018. “You are being asked to leave the premises”: A Study of Eviction in Cincinnati and Hamilton County, Ohio, 2014-2017. http://thecincyproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Eviction-Report_Final.pdf.

4 Finn, Kevin. In-person interview, November 27, 2019.

5 Raymond, Elora, Duckworth, Richard; Miller, Ben; Lucas, Michael; and Pokharel, Shiraj. 2016. “Corporate Landlords, Institutional Investors, and Displacement: Eviction Rates in Single-Family Rentals.” Community & Economic Development Discussion Paper No. 04-16.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!