Recognized as the highest-ranking metro area in Nebraska for economic growth, the city of Grand Island stands on the brink of unprecedented prosperity.

Major employment sectors such as agriculture, education and healthcare have contributed to the steady population increase. However, Grand Island’s growth trajectory has had disparate impacts on its residents. For the roughly 12.5% of residents living at or below the poverty line, accessing economic and educational opportunities can be difficult. Many of the largest employers are not within walking distance of Grand Island’s areas of highest poverty, and weather extremes and a high dependency on personal vehicles inhibit mobility.

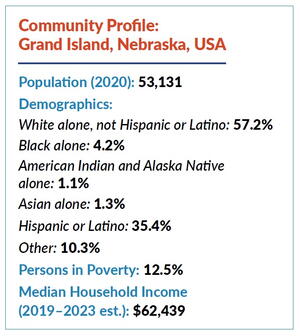

An exploration of poverty in Grand Island reveals a complex interplay of economic, social, demographic, and geographic factors. Over the past decade, the city has experienced significant population growth, especially among the Hispanic community. Hispanic residents currently make up 35% of the population with approximately 21.1% living below the poverty line. Neighborhoods in the northeastern region of the city also experience higher levels of poverty and lower access to quality education and employment opportunities.

In 2015, the city was designated as a Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Entitlement Community, allowing it to receive an annual allocation from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for housing and redevelopment in high-need neighborhoods like those in the northeast. With abundant opportunities for residents and businesses alike, the city is poised to capitalize on its growing economic momentum. Today, local leaders continue to identify gaps in services and strategize methods to uplift all Grand Island residents.

Key Strategies in Grand Island

Equitable Access to Transit and Economic Opportunity

In 2023, the Grand Island city council approved two community plans (Transit Master Plan and CDBG Consolidated Plan) that included efforts to ensure residents have equitable access to transportation and economic opportunity. The basis for those priorities was the result of months of community engagement. This along with a series of grants led to the development of a robust upward mobility initiative that provided a framework for connecting multiple threads of activities, linking low-income residents to employment, education, and empowerment. This work was championed by city administrator Laura McAloon and anchored in the recognition that local governments can play an important role in tackling these issues. Following the adoption of these plans, the city has launched a range of programs and activities aimed at bridging gaps in mobility for residents without personal vehicles and fostering inclusive growth by supporting small businesses, especially those owned by minorities.

McAloon’s connection to her community runs deep. Growing up in Grand Island, she witnessed firsthand the challenges faced by residents, particularly those from low-income or minority backgrounds. This personal connection instilled in her a strong desire to improve the community’s economic prospects. Additionally, her professional experiences outside of Grand Island provided her with a broader understanding of economic development tools and strategies.

Proving the Problem

Understanding the important role data can play in helping to justify investments in public programs, McAloon and her team knew they would need more comprehensive data to effectively convince stakeholders about the need to tackle these challenges. In 2023, staff successfully applied to participate in ICMA’s first Economic Mobility and Opportunity Cohort. Through support from the Gates Foundation, this program seeks to raise awareness among local decision-makers about growing research and newly developed tools that can be leveraged to identify innovative solutions.

McAloon, along with members from her coalition, attended an in-person meeting in Washington, D.C., USA, as part of their participation in the ICMA Economic Mobility program where they were exposed to the Urban Institute’s Upward Mobility Framework. The Mobility Metrics data presented provided the necessary insights to substantiate the problems and develop targeted solutions. As part of participating in the program, Grand Island received a grant of $30,000 to conduct a study on transportation inequities.

Although there had been a series of previous efforts to study transit in the region, the Grand Island Jobs, Education, and Technical Training (G.I. J.E.T.T.) study placed a priority on gathering input from those most impacted by the current car-centric infrastructure, particularly low-income individuals and families without reliable access to personal vehicles. The study was available in English and Spanish, ensuring that most residents were able to provide their input.

The study’s key findings reinforced those of previous studies and highlighted the limitations of their existing public transportation options. The study found that nearly 20% of residents were without a personal vehicle, and that 29% of respondents reported having to walk 1-4 miles to commute to work, with 40% having to walk 1-4 miles to commute to school. Additionally, the study found that nearly 70% of residents have commutes of 30 minutes or less by vehicle, but the length of time was double or triple for those commuting by foot. Although public dial-a-ride service is available by booking 24 hours in advance through the city’s public transit program, known as CRANE Transit, the study found that less than 1% of respondents reported using public transportation, but that 60% of respondents reported they would use public transportation if it was available and convenient for them.

Armed with an additional set of data, Grand Island continues to push for the creation of a limited fixed route or flexible fixed route intercity bus service that would connect residents to employment opportunities in Hastings (26 miles south) and Kearney (42 miles west).

Partnership and Collaboration

Local governments cannot move the needle alone. The city has created an interagency and interdisciplinary team to enhance impact through coordination and co-investment. The team consists of representatives from the city, the city administrator’s office, Grand Island School District, Central Community College, Grand Island Chamber of Commerce, and Grand Island Area Economic Development Corporation. While there had been pre-existing partnerships between the participating organizations, this effort was unique given its explicit focus on identifying and reducing economic barriers for historically disadvantaged populations.

Strengthening Small Businesses

The city identified another opportunity to improve the economic mobility of its residents through strengthening their small food business environment. Leveraging rapid grant funds in the Equitable Economic Mobility Initiative through the National League of Cities, the city was able to provide $2,000 in direct assistance for nine entrepreneurs who wanted to grow their food production businesses in the Community Kitchen Pilot Program.

The fund infusion allowed entrepreneurs to expand their operations through activities such as renting a city-secured shared commercial kitchen space, purchasing supplies, or creating marketing. Many of the materials, such as easy access to an existing local commercial kitchen space that was built for the annual state fair but underutilized by the public at other times, directly resulted from feedback from local business owners. By alleviating some of the typical challenges for local small businesses, the city positioned their food entrepreneurs for success.

As a part of the direct assistance, the entrepreneurs attended four training courses and received expert guidance from Central Community College Entrepreneurship Center staff. The courses helped the entrepreneurs learn more about the nuances of owning and expanding their own small food production businesses. In addition to the courses, the city applied a cohort model to connect the entrepreneurs with peers and mentors who would be able to help provide guidance on typical small food production business challenges. By combining the education and networking connections, the entrepreneurs were able to immediately kickstart their businesses for future growth.

Opportunities for Local Government Managers

Local government decision-makers have a unique vantage point that affords the ability to see the connective tissue among disparate parts that can lead to building a broader coalition for greater impact.

Integrate upward mobility activities into local government plans and strategies.

Codifying your intention across various community plans helps to establish a shared and consistent community vision and mission. Local government initiatives have been successful in using these lower-cost strategies to promote upward mobility.

Engage underrepresented communities in designing solutions.

Giving voice to audiences who are often underrepresented in most community decision-making processes helps to bring about other critical aspects of upward mobility, such as dignity, belonging, power, and autonomy. The insights gained from G.I. J.E.T.T. helped to contextualize the pronounced impact and limitations of their existing transportation options.

Mitigate excessive red tape to unleash community potential.

Before proceeding to costly interventions and programs, consider which internal policies, procedures, and fees can be modified to address potential barriers. To mitigate some of the traditionally biggest barriers to receiving financing and resources, Grand Island limited the eligibility requirements of their entrepreneur grant program to just a few essential components: (1) that the entrepreneurs sold their products within city limits, (2) they focused on food manufacturing, and (3) the households made under 200% of the federal poverty line. “We have so many opportunities for economic growth, and for people to take advantage of that, we just need to figure out how to deliver those services to our residents,” explains McAloon.

Using research and data tools can help pinpoint areas of focus and provide a way of measuring progress over time.

Building a common language can go a long way in establishing common goals and shared narratives. The terms economic mobility and opportunity and upward mobility are relatively new. Although they may not be regularly used as part of common local government nomenclature, they provide a way to articulate a broad range of initiatives intended to improve residents’ quality of life.

“We use the data to make our case for all of our grant applications,” says McAloon. Grand Island Area Economic Development Corp has begun using the data from Opportunity Insights and the Urban Institute’s Upward Mobility Framework to help inform business recruitment efforts, demonstrating the versatility of these resources.

Leverage your position to raise awareness on upward mobility challenges and opportunities.

This can help to attract private and philanthropic funding to support and expand programs and activities. Pool limited resources with local businesses, schools, and nonprofits to create mutually beneficial programs that support employment and educational access.

Lessons Learned

Speak to both hearts and minds.

Barriers faced by residents seeking to improve their economic standing may not be obvious to those with greater access to opportunity. When seeking stakeholder support it is crucial to effectively communicate the benefits for that respective audience. When asked about her approach, “I try to tie it to something that I know they care about,” explained McAloon. “I don’t think we would have been able to tackle these issues if we had not had people willing to change their thinking.”

Don’t let perfection hinder progress.

The opportunities to move forward on economic mobility–related issues can be limited. Undeterred by a setback in obtaining state and federal funders for a fixed-route bus system, Grand Island actively pursued viable alternatives such as vanpools, bike/scooter share programs, and multimodal path systems.

Furthermore, the increased collaboration between the city and Central Community College also led to the development of a new plumber apprenticeship program to help combat local workforce shortages and rising housing costs. “If we’re going to solve our local problems, we’re not going to be able to look to the state to help us,” says McAloon, “so, we just have to figure out how to solve the problem ourselves.”

STEVE KING is a senior program manager at ICMA.

KIMBERLEY SIRK is a senior program manager at ICMA.

JUSTIN CHU is a program manager at the National League of Cities.

CELESTE BENITEZ GALICIA is an assistant program manager at ICMA.

Grand Island was a member of the 2023 ICMA EMO cohort program. Information about applying for the 2025 cohort will be available soon here.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!