By Erik-Jan van Dorp

In the Netherlands, city managers (CMs) are the pivots connecting a city's executive politicians and its public services. As public sector chief executive officers, they navigate between political and administrative realities, serving and leading, advising and deciding, and managing boundary-spanning activities.

How do they operate in a role for which no script exists, in a strategic environment that is unfailingly political, ambiguous, and fluid?

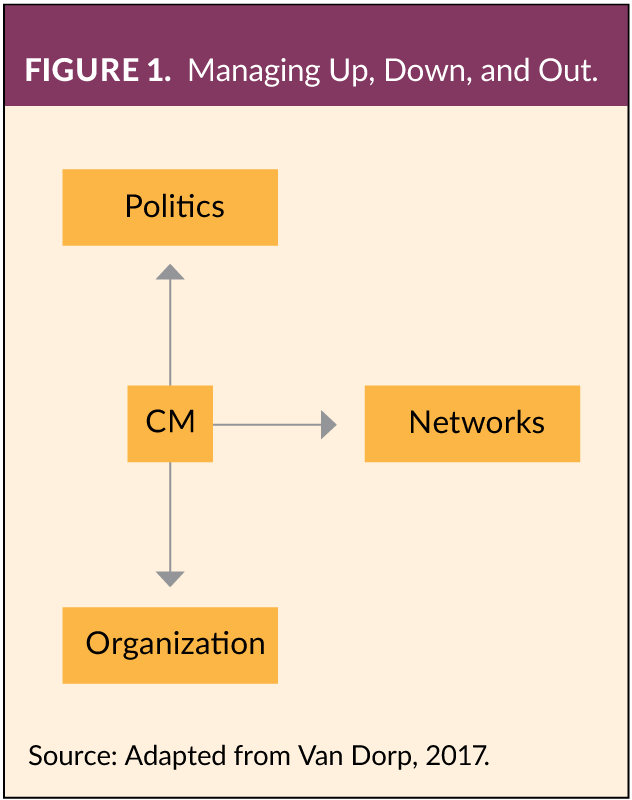

Public management and leadership scholars often distinguish between three directions of management: up, down, and out (see Figure 1). When CMs manage "up," they interact with politicians and other democratically elected office holders.

When managing "down," they interact with coworkers in the community's administration. Finally, when managing "out," they interact with such partners outside the city's administration as community leaders, business owners, and federal or state governments.

Canadian academic and author Henry Mintzberg once asked: What do managers do?1 Inspired by Mintzberg, I have studied three managers of middle-sized cities (up to 180,000 residents) in depth. They are the CEOs of municipal organizations ranging from 700 to 1,700 staff members.

Based on an analysis of their electronic Outlook agendas during 2015 and 2016, fly-on-the-wall observations (182 hours of them), and 33 interviews, in this article I present an analysis of the manager's craft and suggest questions for reflection.

Setting the Scene

In Dutch government, the city manager is a nonpartisan civil servant. A crown-appointed mayor presides over the executive board, which is accountable to a directly elected city council.

The CM is appointed and fired by the board, attends the board's weekly meetings, and, along with the mayor, signs the decision papers of the board. Unlike the other board members, the CM does not have voting powers. The position traditionally also represents the civil servant-in-chief and chief executive officer of the municipal organization.

The aggregate agendas of three managers—listed in this article as CM1, CM2, and CM3—show practices that establish a weekly rhythm.2 CMs generally arrived in the office at 8:45 a.m. and remained until 6 p.m. Mondays were dominated by bilateral meetings, beginning with the mayor and direct reports.

The weekly meeting of the board of mayor and aldermen and possible follow-ups or joint site visits are regular fixtures on Tuesdays. This board meeting sets the pace of the municipal organization. It was perceived by civil servants as the pivotal locus of political decision making affecting the organization. This is where policy proposals submitted by the administration survive or get killed.

Wednesdays began with the city's management team meeting of all top public servants, another key reference point in the week. The remainder of Wednesday is often spent on visits to city agencies or in regional networks.

Thursdays are mostly devoted to managerial work inside the organization, often with time reserved for the works council, bilateral meetings with staff and internal socials, often followed by a meeting of the city council or a council committee.

Fridays are for contemplation and various activities. They are often cut short until no later than 2:30 p.m., after which the weekend comes with ample readings that feed into yet another week.

Managing Up: Adviser-in-Chief

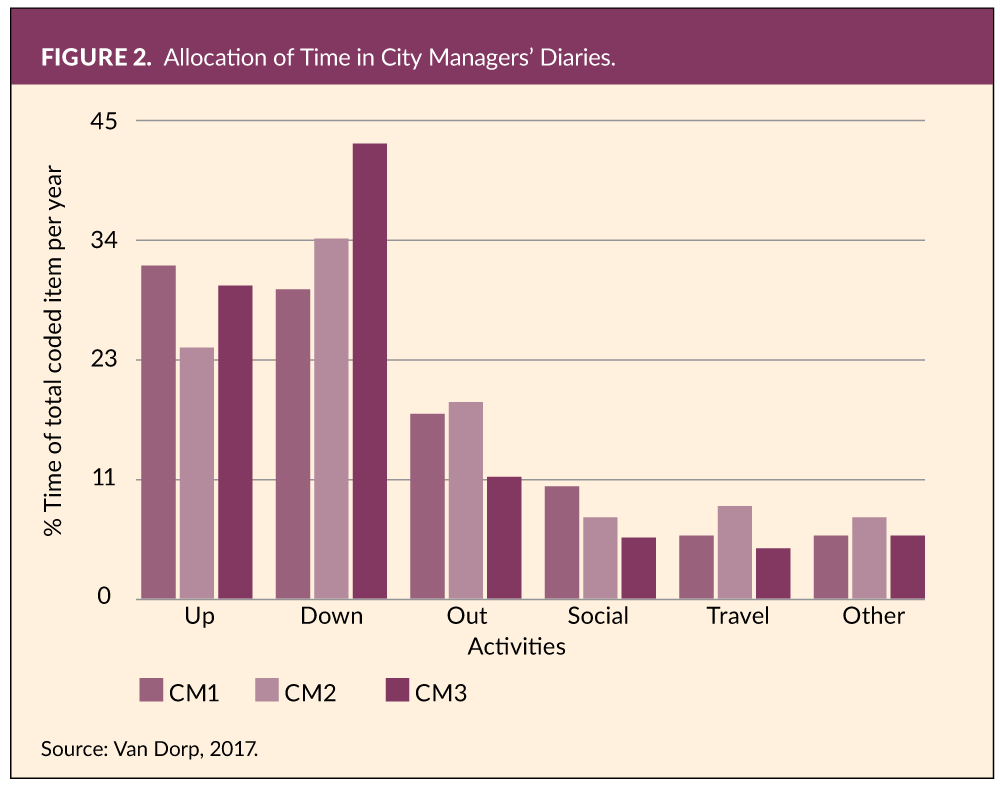

As Figure 2 suggests, three managers prioritized their role as adviser-in-chief by their attendance in settings with political office holders (POHs). The majority of this time was passed in collective settings, with multiple POHs present, including the weekly executive board meeting.

These hours were largely represented by meetings that take a long time—the executive board meetings and the city council meetings. The remainder of the week was spent apart from POHs.

The CM is adviser-in-chief to the mayor and aldermen. This position, however, is not a given and must be earned. One mayor observed: "It is not the case that when a city manager gives her opinion, all board members will take a bow. It is a position that needs to be earned and to some extent, needs to be fought for."

CMs need to acquire standing among POHs to fulfill this role, in a setting also populated by political advisers who compete for their position.

Managing Down: Organizational Stewardship

Figure 2 shows that the observed CMs spent most time on the management of their organizations. The majority of this time was spent attending to direct reports, other managers, and staff.

All CMs spent the most time with direct reports, reflected in less time spent with other people in the organization. The absence of desk work in a diary is confirmed by the observations. It has little place in the diary or in everyday life. Two CMs did not even have a desk.

CMs actively reform their organizations. They do not intend to leave the organization as they found it. All three CMs were involved in some form of a program aiming to improve the organization and reshape its behavior.

It is part of their job perception to monitor and steward the organization's current performance, as well as (re)imagine its future in light of evolving public and political demands that include financial, technological, and other contextual changes. This reflects an attitude of stewardship vis-à-vis POHs. One CM says, "I think it is very important that there is the will to do better in the organization."

The most important lever to create organizational capacity for CMs is the board of directors, which is the management team of the city administration. CM2 spoke for all three when she observed that, "The quality of the organization starts with the quality of the board of directors." CMs were keen on having the right people as part of this board. One of them let go of two directors and hired a new director in her first month in office.

The management team monitors the state of the organization based on a dashboard of parameters. "Hard" parameters include absenteeism; annual employees' appreciation survey; exhaustion of budgets; external hiring; and full-time employee formation. "Soft" indicators are gossip and hearsay on how well pivotal actors or units perform.

This information reaches the CM through informal conversations with civil servants, POHs, and members of the CM's entourage. When certain units underperform may declare them top priority and place them under her or his direct supervision.

Managing Out: Boundary Spanning

"Out"—activities in networks—tended to come third in the attention hierarchy. CM1 and CM2 spent 17.3 percent and 18.6 percent of their time, respectively, in networking activities.

CM1 divided her time across local, regional, and national networks, while CM2 focused on regional and national networks. CM3 spent little time on external management (11.5 percent). Networking activities were less prominent in her diary and fairly isolated rather than habitual.

CMs connect and lobby with colleagues in neighboring cities and governance levels in regional cooperation. None of them work in splendid isolation—beautifully expressed by the prominence of the meeting table in their offices. They are, of course, by and large preoccupied with the POH—organization nexus. Given their pivotal position in the organization and role as secretary of the board of mayor and aldermen, this is hardly surprising. Still, boundary spanning in networks is part of their craft.

All CMs agree that collaborative governance is important, but the demands of managing up and down can and often do take over. The rules of the game in government seem to favor internal over external activities.

CM1 started her position by actively investing in regional involvement but paused some of these efforts when her vertical managerial tasks seemed more pressing. CM3 also started in her current position and prioritized vertical managerial work over horizontal networking activities.

In contrast, CM2, who had been in office since 2004, made ample time for regional and national networks. This may hint at a lifetime cyclical effect, suggesting that upon taking office, CMs first attend to internal matters and try to get their organizations in shape before they get involved in external networks.

Capturing the Craft

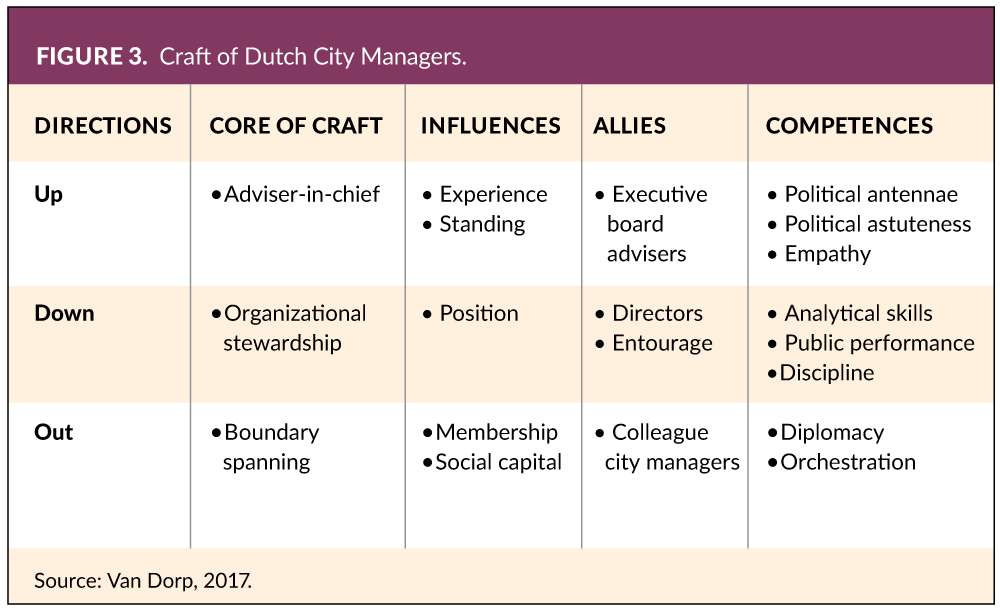

Ultimately, the Figure 3 typology is not about a set of tasks, roles, and competencies. The point is that CMs deploy a repertoire of skills, tricks of the trade, and rules of thumb. Mastering the craft means that CMs exercise judgment in applying the right mix of skills and interpretations at a given moment in a local context.

My fieldwork, however, suggests that the central tension that Dutch CMs experience in doing so is between a "greedy" vertical axis of managing up and down and a strategically important, but always somewhat less pressing, horizontal axis of managing out.

The analysis suggests that the craft of Dutch CMs consists of three core aspects: being adviser-in-chief, managing organizational stewardship, and managing boundary spanning. There are tensions between these aspects that managers need to balance to execute their role effectively.

The findings show that these Dutch CMs consistently allocate most of their time to management of their organizations (down) and advising political office holders (up). Taking part in networks (out) is believed to be important, but the diary analysis shows that less time is spent on networking activities than is spent on the former levers.

The bulk of their work takes place within the hierarchy. I do not argue that networking does not happen but rather that the observed CMs themselves engaged much less in boundary-spanning work than would be expected in a 21st century networked society.

To date, their craft continues to be mainly organized along the vertical up-down axis, emphasizing traditional elements of the bureaucracy.

Call for Reflection

City managers will need to reflect on their roles and the context in which they work. Those who end up as captives of city hall are not an exception. This raises the question of who gives strategic direction to networks and collaborative governance—if not the CEO of the municipal organization?

CMs in effect were largely missing-in-action when it came to managing out. They realized its strategic importance and paid lip service to it, but in their day-to-day routines they are largely trapped in the demands of the hierarchy.

I end this article with three questions for public managers to ask themselves:

How do you allocate your attention and physical attendance? Are you in control of your agenda?

How can managers foster personal resilience to face tensions in government that is complex, ambiguous, fluid, and greedy? How do you cope with pressing demands?

How are you visible and relevant in your organization, without risking being invisible and irrelevant to network partners and residents in your community?

Endnotes and References

1 Mintzberg, H. (1973). The Nature of Managerial Work. Harper & Row Publishers: New York.

2 See Van Dorp, G.H. (2017). "Trapped in The Hierarchy: The Craft of Dutch City Managers." Public Management Review. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1383783 for the full paper, including methods and results.

Erik-Jan van Dorp is a Ph.D. candidate, Utrecht School of Governance, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands (g.h.vandorp@uu.nl;@erikjanvandorp).

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!