By Leonard Matarese, ICMA-CM, IPMA-CP

How looking at the aftermath of this tragedy provides insights that can help communities plan with the goal to prevent or mitigate the devastation of future events

Parkland, Florida, is the type of community that many Americans strive to be able to call home. Located in the northwest corner of Broward County, its 10 square miles is home to about 33,000 people living in approximately 9,000 households, whose median family income is more than $135,000. The medium home value is approximately $600,000. Many residences are in gated communities; others are on large acreage lots.

Parkland is a young community—the average age of a resident is 41 years. Many families moved here to feel safe—the crime rate is extremely low—or to allow their kids to attend modern, successful public schools. Parkland is a family-oriented community, with nice parks and open spaces and few commercial establishments. The city library and recreation center are focal points.

Residents living in Parkland reported a generalized sense of “complacency” before February 14, 2018. On that day at 2:19:54 PM, this world changed forever. At that exact moment, a teenage former student of Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School entered the school armed with an AR-15, and in the course of eight minutes murdered 14 students and three adults and wounded 17 more before leaving the building.

After the Tragedy

A series of investigations followed immediately after the tragedy—by local law enforcement agencies, a commission created by the governor’s office, and a separate study commissioned by the Broward County School Board. As information unfolded, thanks largely to the investigative work of the Sun Sentinel newspaper, which won a Pulitzer Prize for its work, it became increasingly clear that there were serious failures in performance not only by the Broward County Sheriff’s Office (BSO), with whom Parkland contracted for police services, but also by the Broward County School Board. It emerged that numerous incidents involving the shooter prior to the assault could have, should have, alerted authorities to the potential danger.1

By April, the city of Parkland, in response to the understandable concern of residents whose entire image of the community had been terribly shaken, decided to conduct an independent study of ways to improve the safety and security of Parkland residents and visitors. Elected leaders and professional staff recognized that complacency—essentially “living in a bubble”—often prevents critical review of day-to-day activities. Often, we are too close to those day-to-day operations to see the underlying issues that can cost lives.

The Parkland study would encompass a wide range of issues to determine the future of law enforcement in the community as well as to assess safety issues in city facilities and properties. Parkland issued a request for proposals (RFP) for the study and appointed a selection committee of highly respected local law enforcement officials to recommend the organization to be awarded the contract.

The selection committee tapped the Center for Public Safety Management (CPSM, www.cpsm.us), ICMA’s exclusive provider of public safety technical services, which has completed more than 325 public safety studies. CPSM’s mission was to help Parkland leaders understand how they might improve the safety and security of their residents and visitors in the future.

We believe that much of what we learned in Parkland has lessons for other localities, particularly concerning the relationships between residents and the police before a serious event occurs. Our resulting report also suggests a course of action that local governments should consider when a tragedy affects their community. The entire study can be found on the CPSM website.

CPSM was called in after the fact, but periodic assessments of all aspects of school/community safety can change outcomes in the face of a disaster like the one that befell Parkland.

What to Ask in a Safety and Security Review

Here are seven questions for local government and public safety leaders to ask in a safety and security review.

1. How have the role and training of school resource officers (SROs) changed? Are your SROs prepared?

The first school resource officer (SRO) program in the United States began in the late 1950s with the goal of improving the relationship between the local police and youth. Officers were placed in schools on a full-time basis to serve as teachers and counselors. The National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO), created in 1991, adopted the “triad” approach for law enforcement programs in the schools—the role of the school resource officer as that of a teacher, counselor, and law enforcement officer.

However, the expectations for the position of SRO changed dramatically starting with the shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado in 1999 and intensified as the number of school shootings continued to increase. Now the emphasis is on the SRO as a warrior, responsible for engaging, alone if necessary, armed invaders in schools. In fact, the SRO assigned to Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School failed to respond to the shooting and remained outside the building.

Several members of focus groups convened by CPSM during its study were quite vocal in their condemnation of the personal conduct of several members of the Broward County Sheriff’s Office (BSO) in connection with the February shootings. One individual stated, “At the time that we needed them most, there was an epic failure; it occurred before, during, and after the shootings.” Others suggested that what has been exposed was a lack of training and staffing at the schools.

Numerous participants questioned the amount and quality of training provided to deputies and, in particular, SROs. Others described a significant “breach of trust” that occurred in the wake of the February shootings and suggested that this situation must be openly discussed and addressed before reestablishing trust with the community. One parent indicated, “My kids do not feel safe in the hands of the BSO [Broward County Sheriff’s Office].” Another person stated, “BSO is a joke to teenagers.”

Participants in the focus groups made it very clear that they were personally aware that “the SRO position is undesirable because the expectations are so high.” Nevertheless, they believed that every effort must be made to provide incentives for officers to take these positions.

2. Does the municipality closely monitor activities, especially disciplinary actions, and identify troubled students in local schools?

Some school systems have been reluctant to take disciplinary action against students violating school policies and even the law. In Parkland, the commissions studying the events at the high school found that the individual who allegedly committed the shootings was identified numerous times as a potential danger; yet no action was taken. Thus, the schools and the sheriff’s office both potentially missed opportunities to divert him. Localities should examine regularly what is being done in their school systems to identify problem students as early as possible.

3. Are the police staffed and organized properly to ensure regular interaction with the community?

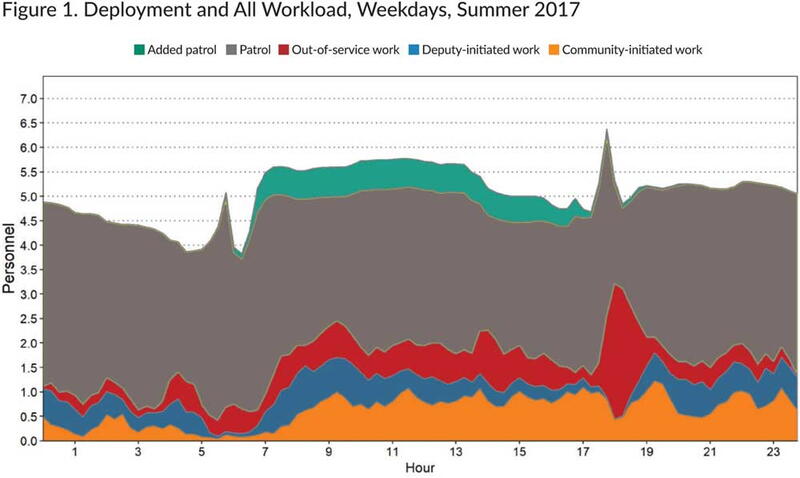

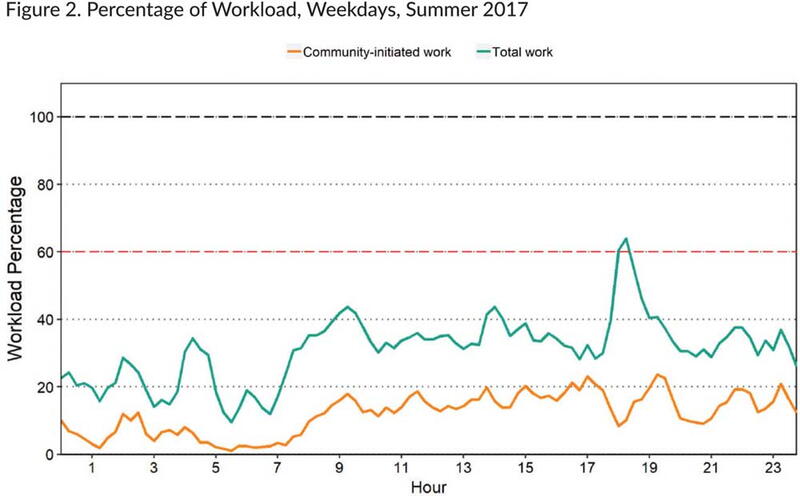

Police chiefs often lament that their officers are too busy to effectively perform community-oriented policing activities. But has the department conducted a meaningful workload analysis to determine whether officers are deployed properly to ensure that they have available time for proactive functions when they are responding directly to calls for service? CPSM found that the workload and staffing for BSO deputies assigned to Parkland left ample time to perform such functions, but that it was not considered a priority for the agency. Figures 1 and 2 show the results of the analysis.

4. Are 911 calls routinely monitored and reviewed to ensure that response to high-priority calls is occurring as expeditiously as possible?

Is there someone in the organization responsible for continuously analyzing whether response times are occurring within acceptable limits as defined by the locality? And are response times analyzed using not just citywide average times, but also by zone or beat and seasonally? Are response times measured from time of receipt to actual arrival of responding units? This is particularly critical when 911 calls are directed to a call center and then transferred to the dispatching agency, as was the case in Parkland, with a resulting delay in response to the shooting incident.

5. Has there been a meaningful review of security in all public facilities in the community? Is it updated on a regular basis?

Such a review should include not only the obvious facilities such as city hall and courtrooms but also all public places where residents and visitors gather, including parks and libraries. Are city employees part of the security plan? Are they charged with closely monitoring and rapidly reporting suspicious activities of visitors to city facilities? Is there in place a way to monitor and identify who should be on specific properties? In Parkland, the recreation center is a very active facility for community activities for adults and children. However, we found that there was no way for recreation supervisors to readily identify who should be present there.

6. For police services (either contracted or internally provided), is there a clear, measurable set of performance standards?

If performance standards have been set, are they monitored on a regular basis and is there a resolution process for when those standards are not met? Do elected officials and city administrators regularly review performance, and is the achievement of these standards part of the evaluation of the police department and police chief?

7. Are local government staff members trained and regularly updated on the appropriate response to emergencies?

In addition to quickly calling for 911 assistance, local government staff should know what actions they should be taking while awaiting the arrival of first responders. For example, are all employees familiar with the location of external automatic defibrillators? Do they have up-to-date training on how to use them and perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)? Are Stop the Bleed kits located in local government facilities and are staff members trained to use them?

The Need for Regular Review

The CPSM final report covers a very broad range of issues and this article has suggested just a few of the areas that an independent safety and security analysis should address. We know that by asking these and many other focused questions, in advance of an emergency, tragedies may be averted or at least minimalized.

Hopefully, few communities will ever experience the trauma and loss that the residents of Parkland suffered. But local government leaders can better prepare their communities to prevent or mitigate the devastation of many events that endanger their residents by seeking assistance in reviewing public safety exposures on a regular basis.

Endnote

1 For a detailed report on these failures, go to http://projects.sun-sentinel.com/2018/sfl-parkland-school-shooting-critical-moments/.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!