By Joshua Franzel, Gerald Young, and Rivka Liss-Levinson

As the capabilities of information and communication technologies have advanced and become more accessible, traditional sectors of the economy continue to evolve in the wake of the Great Recession. And, as organizations of all types and sizes attempt to address longer-term legacy benefit costs, there has been increased focus on the role of the “gig” or “contingent” worker, and related others working in “alternative employment arrangements.”

While these positions cannot be neatly categorized, in 2017 the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) identified five generalizable characteristics of gig workers: (1) self-employed and performing single projects or tasks on demand; (2) providing labor services; (3) working for pay (not providing services in-kind); (4) obtaining work or performing services either offline or online through applications or websites; and (5) performing gig work either part time or full time.1

Even though these arrangements are receiving more attention in today’s labor market, exploring how these workers engage with traditional public and private employment structures, along with broader attempts to formally define their roles, is nothing new.

BLS Research

As a U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) researcher highlighted in 2001, “The phrase ‘contingent work’ was first proposed by labor economist Audrey Freedman in 1985 to refer specifically to ‘conditional and transitory employment arrangements as initiated by a need for labor—usually because a company has an increased demand for a particular service or a product or technology, at a particular place, at a specific time.’”2

Since at least 1995, BLS has periodically issued supplemental surveys on the roles, demographics, industries, occupations, employment characteristics, and other attributes of contingent workers.3 Through these BLS data collection efforts, certain occupational groups appear to more likely align with contingent/gig work:4

1. Arts and design (musicians, graphic designers, artists).

2. Computer and information technology (web developers, software developers, computer programmers).

3. Construction and extraction (carpenters, painters, construction workers).

4. Media and communications (technical writers, interpreters and translators, photographers).

5. Transportation and material moving (ridesharing, delivery services, personal shoppers).

Based on interviews with gig workers, BLS has highlighted that these positions balance flexibility of schedule, variety of tasks, and passion for work with inconsistency in work levels and income, irregularities in scheduling, and (importantly) lack of health, retirement, paid leave, disability, and other quality-of-life benefits that are typically offered by many public and private employers.5

While the exact number of gig workers is not known, a range of organizations from the government, academic, and private sectors estimate these positions to make up around 30 to 35 percent of the labor force, with many forecasting that this number will increase in the coming years.6

Local Government Trends

What is known about how these arrangements interface with local governments as employers?

In 2018, the Center for State and Local Government Excellence (SLGE), as part of its annual state and local government workforce survey—conducted in coordination with the International Public Management Association for Human Resources and the National Association of State Personnel Executives—began asking government human resource professionals about what, if any, staffing needs they had filled with gig/contractual workers over the past year.

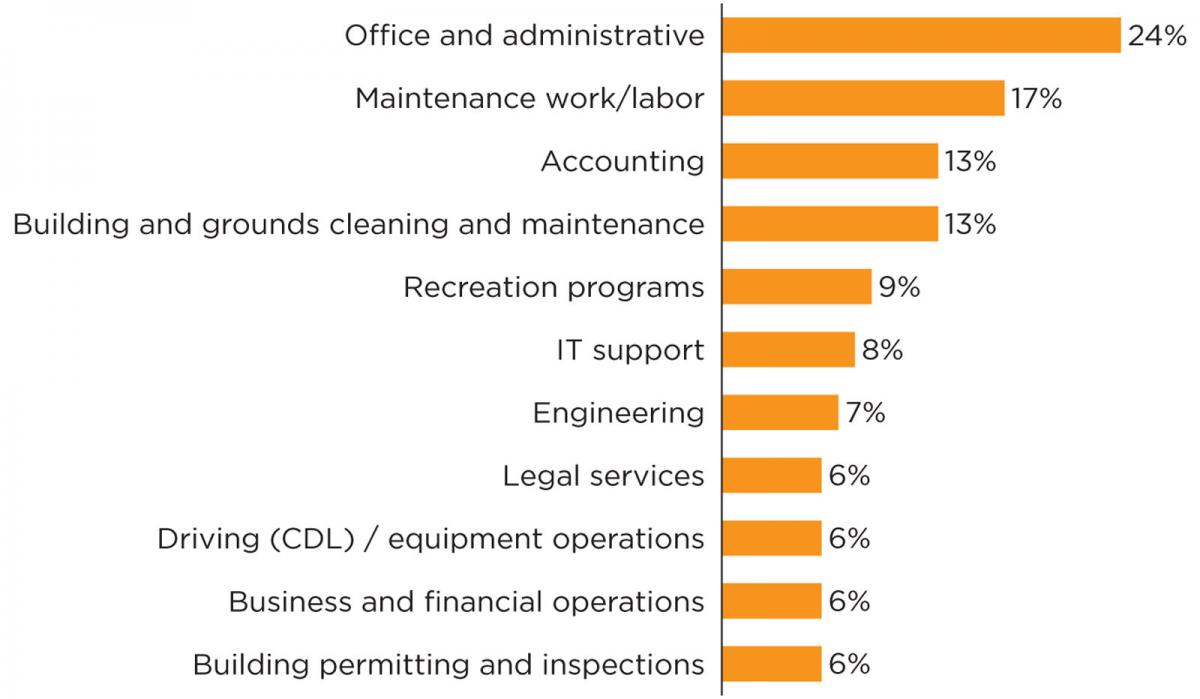

Figure 1 highlights the gig services most often cited by local government respondents. As can be seen from the list, these positions range from knowledge workers that require advanced education and training to more manual labor.

Figure 1. Top Gig Services Most Cited by Local Government Respondents [n=216]

Other position categories also being filled by these arrangements are in health care, web development and other IT positions, social services, skilled trades, and auto maintenance, among others. Interestingly, a handful of respondents also added that they are using gig arrangements for grant writing, general labor, campground monitoring, and meter reading.

Coming on the heels of the Great Recession and many years of furloughs, pay cuts, and layoffs, it may be that local government managers are opting for gig workers as a means to avoid rehiring full-time workers when fiscal uncertainty and budget pressures remain a concern.

This would fit with predictions that past higher levels of local government employment will not be returning.7 There is also ample precedent for gig workers in development services, tax accounting, and other cyclical operations, where tasks might be specific to a few large subdivisions, or processing of local income or property tax filings.

Beyond that, where technology facilitates independent action through cloud-based software, virtual meetings, and even telemedicine, a need for in-house staff may be perceived as less crucial than it once was.

Key Questions for Local Governments

It will be important to track how gig workers as a share of the local government workforce will evolve going forward and if they will be leveraged in more service areas. Also, the implications for the current, traditional local public workforce have yet to be fully explored.

It is clear, however, that key local management questions need to be considered. Here are a few:

1. How will gig workers interact with their full-time or part-time counterparts? How will local managers and HR professionals navigate equity issues between these groups?

2. How will the long-term actuarial models and management of retirement plans be affected by a greater share of public sector work being done by nonemployees? Similar questions can be asked of health insurance structures.

3. Given that many local governments offer a range of benefits to their employees, how will the lack of these benefits offered to gig workers impact the health and retirement readiness of these workers (who may also be residents) and their long-term quality of life? Will social services and programs, at various levels of government, need to be adapted to account for the future needs of this cohort?

4. Will the transitory nature of gig workers impact the workforce’s engagement with and accountability to local residents?

These and other related questions will be explored through future SLGE research, including expanding on this baseline data as part of its 2019 workforce survey.

Is your local government increasing its use of gig workers? SLGE would like to learn about your experiences. Contact us at info@slge.org.

Endnotes and References

1 “Workforce Training: DOL Can Better Share Information on Services for On-Demand, or Gig, Workers.” September 2017, https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687380.pdf.

2 Hipple, S. “Contingent work in the late-1990s.” Monthly Labor Review, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2001/03/art1full.pdf.

3 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Contingent and Alternative Employment Arrangements” data sets, https://www.bls.gov/bls/news-release/home.htm#CONEMP.

4 Torpey, l. and A. Hogan. “Working in a Gig Economy.” Career Outlook. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2016, https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2016/article/what-is-the-gig-economy.htm.

5 See https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2017.

6 See (1) https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/employment-and-growth/independent-work-choice-necessity-and-the-gig-economy; (2) http://money.cnn.com/2017/05/24/news/economy/gig-economy-intuit/index.html; (3) https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2016/article/pdf/what-is-the-gig-economy.pdf; (4) https://qz.com/472248/contingent-workers-now-make-up-34-of-the-us-labor-force.

7 Maciag, M. “A Downsized Public Workforce May Be a Permanent Consequence of the Recession.” Governing, December 2017, http://www.governing.com/topics/mgmt/gov-suppressed-staffing-levels-government-recession.html.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!